BOOK REVIEWS & RECOMENDATIONS

I love books. I have an extensive library and read voraciously. Years ago I started reviewing books for Amazon. I stopped doing that because I realized I was feeding a machine that was undermining local booksellers and compromising a way of life. My practice today is to almost exclusively buy books through local bookstores. If I read a review of a book I like or someone recommends something interesting, I email the title to the owner of my local book shop, Jessica's Book Nook, and he orders it for me. I pay a little more for a book - but believe me it is worth it.

The goal of this section is to direct people interested in Shelley and his circle to books of interest. I will try to review as many of them as I can, but in other instances I may simply point you to books of outstanding importance that fall into the category of essential reading.

Shelley in the 21st Century. By Graham Henderson

A link to my article at the Wordsworth Trust Blog.

‘The Modern Disciple of the Academy’: Hume, Shelley, and Sir William Drummond. By Thomas Holden

Sir William Drummond (1770?-1828) enjoyed considerable notoriety in the early nineteenth century as the author of the Academical Questions (1805), a manifesto for immaterialism that is at the same time a creative synthesis of ancient and modern forms of scepticism. In this paper Thomas Holden advances an interpretation of Drummond's work that emphasises his extensive employment and adaptation of Hume's own ‘Academical or Sceptical Philosophy’. He also documents the impact of the Academical Questions on the contemporary philosophical scene, including its decisive influence on Shelley's philosophical development.

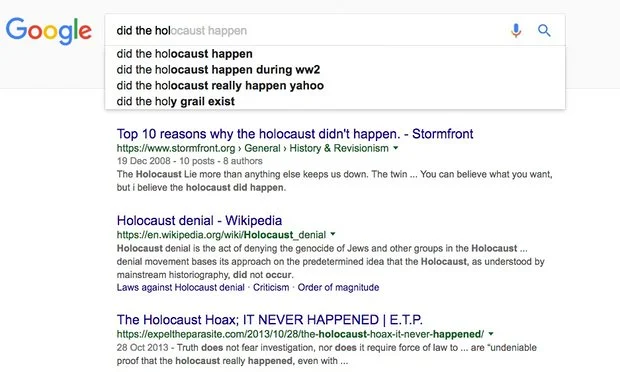

"Google is not ‘just’ a platform. It frames, shapes and distorts how we see the world" By Carole Cadwalladr

"Did the Holocaust really happen? No. The Holocaust did not really happen. Six million Jews did not die. It is a Jewish conspiracy theory spread by vested interests to obscure the truth. The truth is that there is no evidence any people were gassed in any camp. The Holocaust did not happen."

An introduction to 'The Masque of Anarchy' by John Mullan

Professor John Mullan analyses how Shelley transformed his political passion, and a personal grudge, into poetry.

Shelley's Musical Muse

Shelley and the Musico-Poetics of Romanticism explores Shelley’s near lifelong fascination with music and the role it played in the creation of his poetry and his theory of the imagination. As an independent scholar anxious to bring Shelley to the attention of a larger audience, books such as this are an important tool because they can connect Shelley to people who come from very divergent walks of life.

Alexander Larman's "Byron's Women" and the conjoined but contrasting myths of Shelley and Byron

Alexander Larman's new book Byron's Women is just out in paperback and you need to buy it; now. In what may be one of the best written blogs I have come across in a very long time, Larman encapsulates his thesis; and he does not mince words:

The greatest falsehood propagated about Byron is that he loved women. On the contrary, his attitude towards those in his life was mainly a mixture of contempt, violence and lordly dismissal.

In the pages of his book it would appear that we finally we have someone speaking truth to power and by power I mean what Larman calls the "Byron establishment"; an establishment which he asserts has been "permeated by a lazy misogyny for decades".

Elizabeth Rawson - "Cicero; A Portrait"

I wish I could find a simple way to convince people to read about one of my heroes, Marcus Tullius Cicero. Today he seems so remote. However a very great deal of our modern world (our laws, our language our philosophy) is founded upon his thinking. And for those of you interested in Shelley, he is actually extremely important. Shelley was very familiar with his writings and said of him, "Cicero is, in my estimation, one of the most admirable characters in the world." Much of the underpinning for Shelley's skepticism is derived from his reading of Cicero; whose philosophical dialogues are cited in his letters as a "favourite". The "Tuscan Disputations" were an extremely important source for aspects of "Prometheus Unbound". If you want to know Shelley, you must understand Cicero.

Gabriel Charton - Glaciers of Chamonix

Tony Astill has done students of Shelley an inestimable favour by offering a gorgeous facsimile edition of Charton’s "Glaciers de Chamouny". If you want to get a sense of what Shelley saw with his own eyes, this is the book for you because it EXACTLY follows the route he followed and contains startling, contemporary images of Chamonix, the Mont Blanc Massif and the Glaciers of Chamonix: Glace de Mer and Bossons.