David, or The Modern Frankenstein: A Romantic Analysis of Alien: Covenant by Zac Fanni

I was very excited to hear that Shelley's poem Ozymandias features prominently in the new movie in the Alien franchise: Alien: Covenant. The poem's theme is woven carefully into the plot of the movie, with David (played again by Michael Fassbender) quoting the famous line, "Look on my works ye mighty and despair."

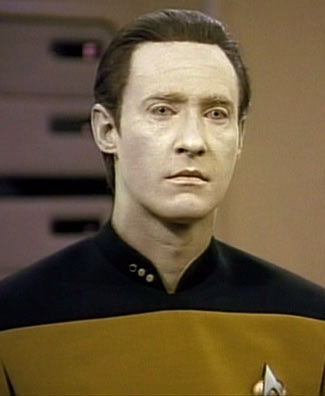

David, as followers of the movies will know, is a xenomorph - a "synthetic humanoid" - one in a long line of such creatures, one of the most famous being Data in Star Trek: The Next Generation.

That David quotes the poem without a trace of irony is central to the question of whether or not these creatures are fully human or not. For David not to see that Shelley is employing one of his trademark ironic inversions, suggests that something is not quite right with him. That he mistakenly attributes the poem to Byron is another twist altogether.

What immediately drew me to Zac Fanni's excellent article was his discussion of the Ozymandias scene. However, what I found amounted to so much more. We are offered a kaleidoscopic array of classic romantic allusions including some which are more obvious, for example Frankenstein and Rime of the Ancient Mariner; and some that are decidedly less so: Shelley's Alastor makes an unexpected appearance!

Now, does this make the movie an expression of Shelley's philosophy or values? Alas no. The movie strikes me more as an empty repository of romantic motifs and riffs than anything else. Some of these are undoubtedly extremely clever, others are surely accidental or unconscious. The philosophy which underpins the movie is one of profound cynicism and nihilism. Shelley was a skeptic, not a cynic and certainly not a nihilist. As Paul Foot observed, "It’s very, very easy for the skeptic to topple over into being a cynic. And a cynic can never be a revolutionary. [It is] absolutely impossible for a cynic to be a revolutionary because they don’t see the possibilities - they don’t believe that it’s possible that working people can change their lives and change society." Read more about this here.

One point of overlap between the many Alien movies and Shelley is that women take the lead. Foot observed this of Shelley when he wrote, "All through Shelley’s poetry, all his great revolutionary poems, the main agitators, the people that do most of the revolutionary work and [who he gives] most of the revolutionary speeches, are women. Queen Mab herself, Asia in Prometheus Unbound, Iona in Swellfoot the Tyrant, and most important of all, Cyntha in The Revolt of Islam." In the case of the movie franchise we have Alien's Ripley (Sigorney Weaver), Prometheus’ Elizabeth Shaw (Noomi Rapace) and Covenant’s Dany Branson (Katherine Waterston). These are all strong women, but there the similarities end. Shelley imagines his female leads as engaged in important revolutionary work, they are gradually but inexorably changing the world for the better. The same is not true of Ripley, Shaw or Branson, as Fanni himself notes. Ripley makes a lonely, solitary escape, while the other two die miserably in the grasp of an overweening, inexorable fate. This is distinctly un-Shelleyan.

But what about the links to Alastor? Certainly, I think we have to take as a starting point that not one single person connected with the movie has ever read or even heard of Alastor. But that does not mean that the themes of Alastor do not resonate, and Fanni makes a very compelling case for this. Roland Duerksen, in his short but brilliant book, Shelley Poetry of Involvement, makes the point that 'Shelley's art always brings us round to a direct confrontation of what it really means to live - which for him is synonymous with really to love." Fanni's version of this is this: "In “Alastor,” Shelley shows us our two conditions: first, that the poverty of our language and imagination causes us to be deeply, metaphysically anxious about our nature; and second, that pursuing answers to these mysteries entails transcending the self, a form of death where you become part of the great design."

The term "alastor", which suggests a pursuing vengeful spirit, was suggested to Shelley by his friend Thomas Love Peacock. Duerksen's conclusion is, therefore, that Shelley must have thought of "separateness or alienation" as that just that vengeful spirit. Very clearly alienation and separateness are one of the central themes of Covenant, indeed all of the Alien movies. The difference, however, between David and the young poet of Alastor, is that the latter aspires to be something more. That he fails is the tragedy of the poem. And he shares a fate very different from that of David in Covenant - he dies. Duerksen describes the poet's "propensity toward unloving, isolated existence" as his great failing. Had he detected it earlier he would have awakened to the potential for what Duerksen calls "human, imaginative identification" with the world.

David, on the other hand, seems to revel in his isolation, learns nothing from it and yet ultimately triumphs. Whereas Shelley extols the maternal power of nature in Alastor, in the world of Covenant, David has absolutely overmastered nature; in fact almost sterilizing it. In one of the great passages from A Defense of Poetry, Shelley contends that love "is an identification of ourselves with the beautiful which exists in thought, action, or person, not our own." In other words, love is empathy. He later defines imagination as the act of putting oneself in the "position of another." Empathy again - or what Duerksen calls "involvement". The world of Covenant is utterly devoid of any empathy whatsoever and David is utterly lacking in imagination. The xenomorph learns virtually nothing from his exposure to humans. This point is brought home in what Fanni calls "One of the most disturbing moments of the film," which, he continues, "involves no aliens at all: our protagonist, Dany Branson is physically overpowered by David, who bends over her with a pantomimed kiss, threatening sexual violence by whispering, “Is this how it is done?” No empathy, no identification with the other and no imagination. Just the horror of the vacant abyss of self-involvement.

The principal difference between the young poet of Alastor and David is that the poet at least attempts, as Duerksen says, to expel "solitude and silence, replacing them with imaginative union and creative expression." The message of Alastor is ultimately hopeful and uplifting. And the full flowering of this optimism came later in in poems such as Prometheus Unbound and The Triumph of Life. We can see the possibility for growth and development. On the other hand, Covenant presents us with a nihilistic vision almost completely devoid of the possibility for human redemption.

So my conclusion is that while Covenant has many roots in the world of the romantic poets (as Fanni has so ably demonstrated) its fruit is poisoned, sterile and antithetical to everything dear to that world, and in particular to Shelley.

Zac Fanni is a Toronto-based freelance writer and college professor teaching in the Humanities. He tells me he is convinced of two things: that Penny Dreadful is the best television show to have ever aired, and that he will one day get a tenured position at Xavier's School for Gifted Youngsters. Both of these things, he says, are probably unlikely. You can find him on twitter here, and on Youtube here.

And now this spell was snapt: once more

I viewed the ocean green,

And looked far forth, yet little saw

Of what had else been seen—Like one, that on a lonesome road

Doth walk in fear and dread,

And having once turned round walks on,

And turns no more his head;

Because he knows, a frightful fiend

Doth close behind him tread. (442-451)Samuel Taylor Coleridge, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner

Dread is the fear that lingers, the fear that condenses into an apprehension so tangible that it becomes a part of our environments: once the literal visage of death has been witnessed (in the female, male or double-mawed alien form), the mariner’s ship, the scientist’s laboratory and the space jockey’s stasis pod all become stained and saturated with its horrific presence. This is what 1979’s Alien achieved so thoroughly: it made the familial warmth of the Nostromo’s cafeteria congeal into an intimate terror of a subliminal nightmare birthed from the human body.

Part of the perfection of Alien lies in its totality, as it is a film that needs no sequel, no franchise, no epilogue to Ripley’s final log entry. And while we received the obnoxiously competent Aliens, the resulting entries have deadened us to our beloved xenomorph. Yet with the brave and imperfect Prometheus, Ridley Scott’s creatures became more than a perfected source of physical dread–they emerged as the grotesque manifestations of our deep existential dread about our origin, mortality, and meaning. Peter Weyland (Guy Pearce), founder of the company that launches the franchise’s ill-fated missions, opens Alien: Covenant by asking the “only question that matters: Where did we come from?”

As it was with the xenomorph in the previous films, the dread surrounding this question begins with an encounter: the archaeological depictions of alien visitations that form the opening shots of Prometheus both inspire and foreshadow the film’s central quest, a quest that ends when Peter Weyland is bludgeoned to death by the creator he spends his life searching for. This demise provides us with a secularized version of humankind’s fall in Milton’s Paradise Lost, where mankind, seeking godhead, loses all. Killed by his search for immortality, a search that is decidedly male in this franchise (our female heroes avoid this kind of solipsism), Weyland whispers, “there’s…nothing.” It is David (Michael Fassbender), Peter’s android “son,” who alone realizes the dark irony: the questions that matter have no answers. David responds to those final words by telling his creator-father, “I know.”

Ridley Scott’s Alien: Covenant brilliantly steps forward from this point by focalizing the familiar “Jaws in space” story around the lost android of Prometheus. In Covenant, David is a mythopoeic creature whose knowledge of the metaphysical nothingness lurking just beyond our comprehension drives him to create an answer for it. In the process, David becomes both Frankenstein and his creature (finalizing the series’ chain of created beings who seize that Promethean power for themselves), Milton’s Satan (preferring to reign in his necropolis than serve in civilization), and an unironic version of Percy Shelley’s Ozymandias (commanding his victims to “Look upon my works, ye Mighty, and despair!” while creating and using the “lone and level sands” that surround the shattered remains of those endeavors) (11, 14). And while the film’s trailers tell us directly that “the path to paradise begins in hell,”it is their encounter with its ruler that hints at the horrifying truth: there is no paradise to ascend to.

By using David’s metamorphosis to frame the familiar transmogrifications suffered by the Covenant’s hapless crew, Alien: Covenant presents a horrifying inversion of the Romantic pursuit of the sublime – not only are there no meaningful answers to our deepest questions, but the very pursuit of those answers consumes us from the inside out, leaving a literal manifestation of Frankenstein’s “wrecked humanity” to float alone in void of space (Shelley 165). Our survivors, like Coleridge’s Mariner, are condemned to forever “walk in fear and dread” as they recount their tale to reluctant, doomed ears. If, as Percy Shelley wrote, poets “measure the circumference and sound the depths of human nature” (850), David does so to the point of nihilism: he reveals that those depths are empty and capable of reflecting back an inner (and literal) monstrosity.

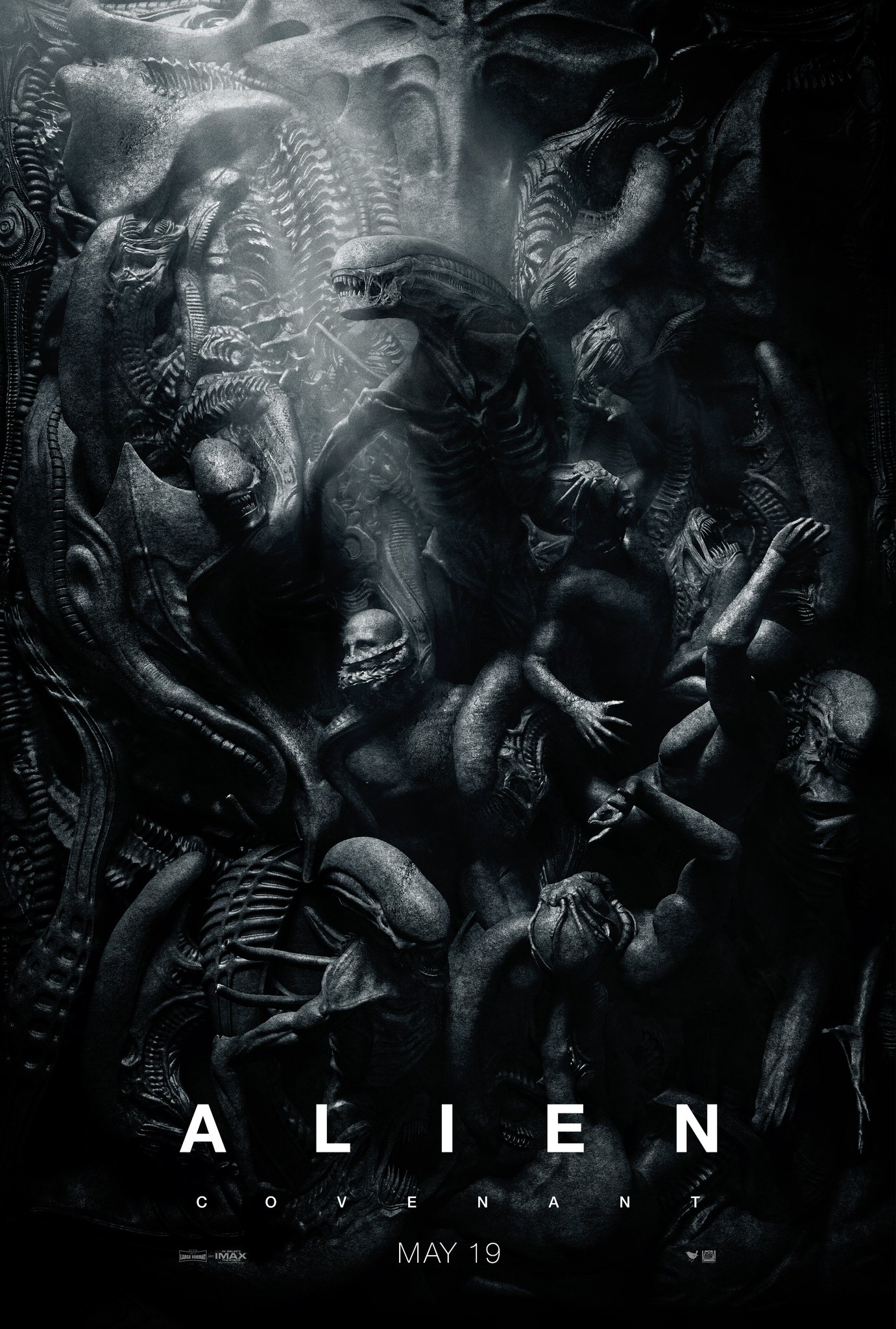

Before we are even exposed to the film itself, the metaphysical dread of Alien: Covenant is prefigured in its marketing. Consider what might just be the best film poster of the year:

The poster retains the inky corporeality of an engraving print, and visually signifies the inverted ascension that becomes the central motif of our prequel films: the xenomorph emerges triumphantly into the sole source of light, atop the suffering, subdued bodies that evoke Giovanni da Modena’s depiction of Dante’s Inferno. These neoclassical figures (where specific personalities are eschewed in favor of an “ideal” human form) also imply a universality–these aren’t characters from the film or franchise, but bodies that instead represent humanity as a category.

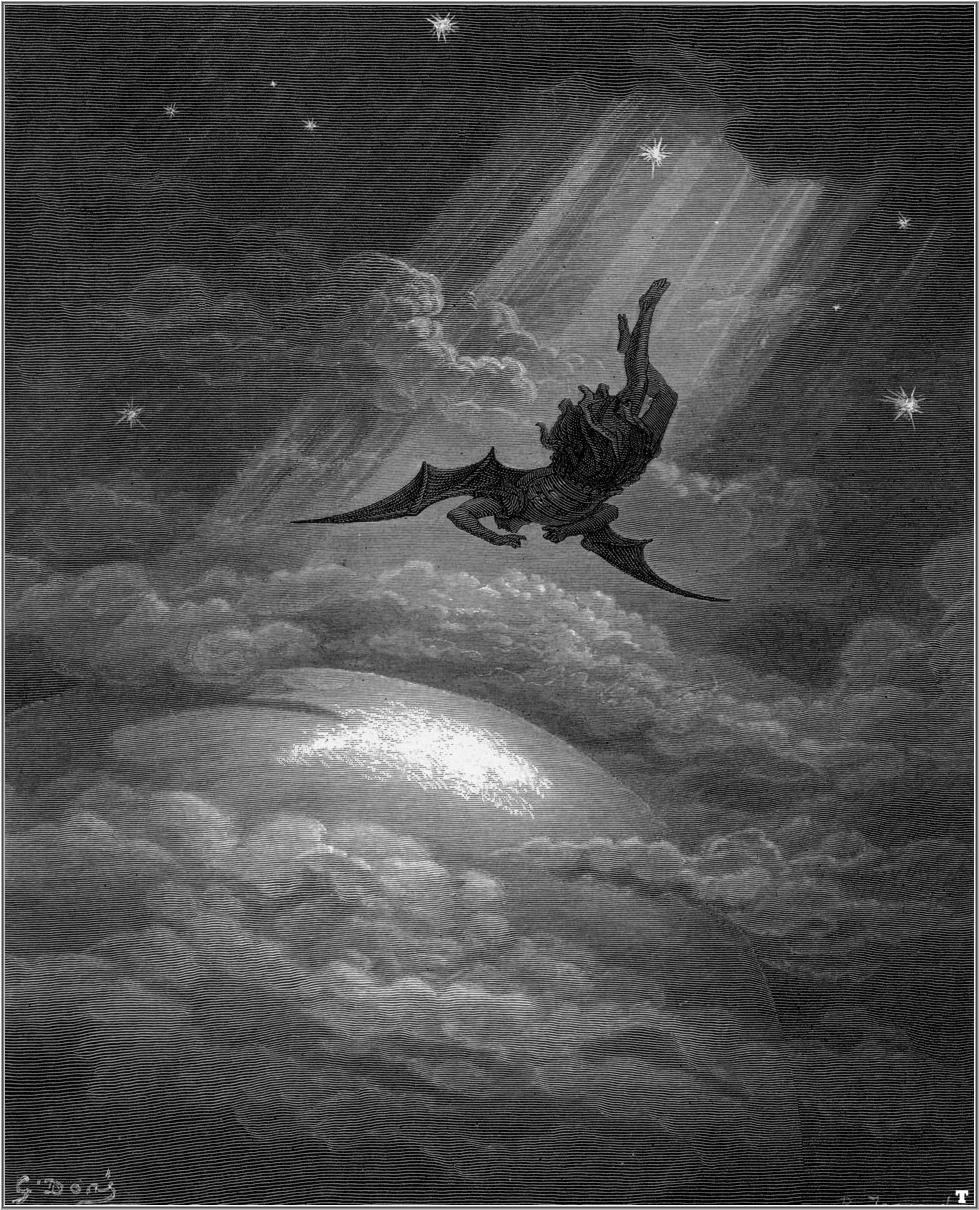

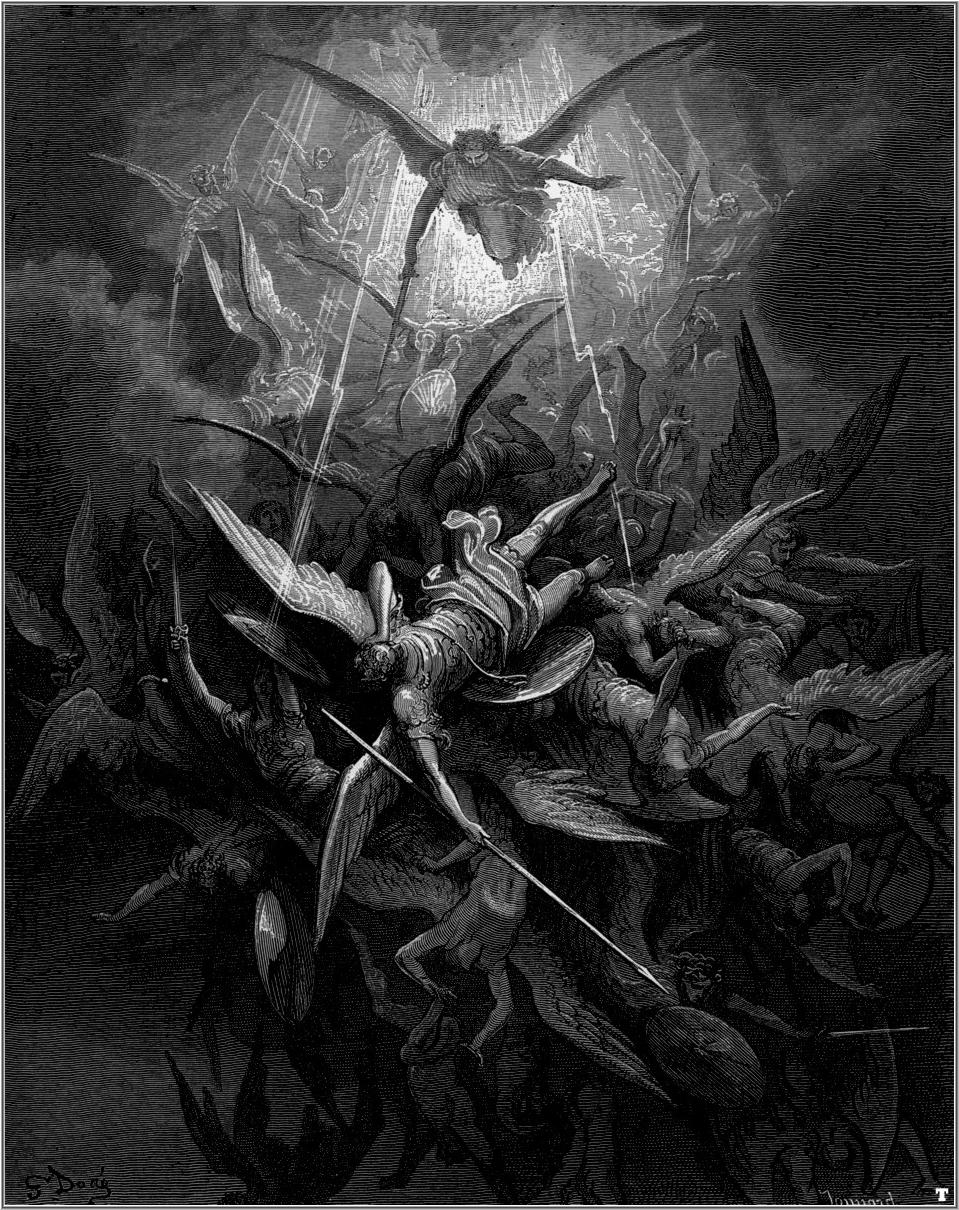

There are innumerable parallels that can be drawn with this image, but Gustave Doré’s engravings for Paradise Lost provide a strong starting point of comparison, especially considering that Ridley Scott once claimed that Alien: Paradise Lost would be the name of the Prometheus sequel. Let’s examine these two illustrations in particular: the first depicts archangel Michael casting Lucifer and his fallen angels out of heaven (1.44-45), while the second depicts Lucifer hurtling towards Earth, eager to corrupt Man and his realm (3.739-41).

In our first illustration [on the right], the vertical arrangement is more traditional: good triumphs, literally, over top evil, with the light source both illuminating the sacred and casting the profane into shadow. In other words, it is the opposite of Alien: Covenant’s poster arrangement, where there is no cosmic ideal to represent–all that exists is a darkness within humankind that emerges into the light, a twisted creature that erupts from the subliminal spaces of our minds and bodies.

In the second illustration [on the left], Satan descends from the heavens to corrupt humankind, God’s new (and perfect) creation. The source of light again both locates the heavens in a more literal way, and (again) frames Satan in contrast to the sacred ideal (the contrast between his dark figure and the heavenly light is particularly extreme), making his descent a direct personification of the Fall (from grace, perfection, etc.) soon suffered by prelapsarian humanity. Again, Alien: Covenant represents an inversion of this motif: evil is not something that arrives from without, but is something that violently, inescapably erupts from within ourselves and as our selves. The nothingness that the franchise’s expeditions seek to confront, the nothingness that Peter Weyland faces as a reward for his life’s labors, is what makes monstrosity possible: seeking to close that existential void engenders our fall, allowing a figure of pure, savage atavism to emerge in our place.

It is no coincidence that Paradise Lost figures heavily in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein–Milton’s poem is the very text through which Victor Frankenstein’s creature comes to understand his own monstrosity. Understandably, the creature identifies with Milton’s Satan, seeing Lucifer as the “fitter emblem” of his condition, and he even envies the fallen angel, telling his creator, “my form is a filthy type of yours, more horrid even from the very resemblance. Satan had his companions, fellow-devils, to admire and encourage him; but I am solitary and abhorred” (132, 133). While the abhorred form draws an obvious parallel to the xenomorph (whose human resemblance constantly reminds us of our bodies’ horrendous mutability), the creature’s more likely analogue in Alien: Covenant is David; what figure other than the android has taken a more coveted place in our collective imagination, precisely because its resemblance to us (in both a physical and metaphysical sense) disrupts our sense of what we are? Our ontological uniqueness, in other words, is threatened by the humanity that can be created.

If you decide to use some sort of Voight-Kampff test to determine your subject’s humanity, the eyes would make for an intuitive starting point – as in Blade Runner, Alien: Covenant features an extreme close-up of a (human?) eye, which we soon realize is David’s. Eyes are an obvious symbolic starting point, as they are the simultaneously the site of both empathy and expression: we observe the subjectivity of others while revealing our own. When characters shield their eyes (as, for example, agents do in the Matrix films), it is a clear symbol for soullessness. This is no different in Mary Shelley’s novel. Victor Frankenstein, after a seemingly fruitless toil to “infuse a spark of being into the lifeless thing” before him, sees “the dull yellow eye of the creature open; it breathed hard, and a convulsive motion agitated its limbs.”

The creature’s eyes signify his life, but also a life that is cast as nonhuman: “the dull yellow eye” reflects an ontological dullness imposed by Frankenstein, who labels the creature as a ‘monster’. It is no mistake that Frankenstein keeps returning, almost obsessively, to the creature’s eyes: he notes that the “luxuriances” of the creature’s lustrous hair and pearly-white teeth only form “a more horrid contrast with his watery eyes,” and when the creature seeks Frankenstein’s company by invading his bedroom (a scene of horrific, tragic proximity perfectly captured by Bernie Wrightson in his comic book adaptation of the novel), Frankenstein notes that the creature’s “eyes, if eyes they may be called, were fixed” on him. It is only the creature’s words that inspire compassion from Frankenstein, who narrates that the creature’s story of profound, imposed loneliness (itself a tragic version of the Romantic preference for isolated contemplation) “had even power over my heart” (58, 59, 212).

The creature’s experience is shared by our own version of him: the android. David’s perfect diction, posture and figure (which Billy Crudup’s character threatens to “fuck up” in the film) are “luxuriances” that only call attention to his nonhuman ontology. As with Frankenstein, it is our proximity to our created entity that shatters our metaphysical preconceptions and causes us to be deeply unsettled: “now that I had finished,” narrates Frankenstein, “the beauty of the dream vanished, and breathless horror and disgust filled my heart.” Victor is “unable to endure the aspect of the being” that he creates (58), and it is this proximate encounter that causes him to flee into the rain-drenched street of Ingolstadt, reciting Coleridge’s “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” to express the dread that pushes him forward (“on a lonesome road”) while preventing him from looking back (446).

Likewise, David’s uncanny humanity (his creepiness factor goes unchecked in Alien: Covenant) propels us away, and the entire plot of the film’s latter half is moved forward by escalating scenes of discoveries about David’s experimentation and intention. One of the most disturbing moments of the film involves no aliens at all: our protagonist, Dany Branson (played impeccably by Katherine Waterston), is physically overpowered by David, who bends over her with a pantomimed kiss, threatening sexual violence by whispering, “Is this how it is done?” This is Covenant’s version of the creature’s bedroom invasion in Frankenstein, replete with threat of sexual invasion endemic to the Alien films. David not only calls direct attention to his uncanny difference, but also construes that difference as a threat.

It is this knowledge of the human-like creature gained from this kind of close encounter that causes the heart to palpitate in the “sickness of fear” (Shelley 60). Even the word ‘monster’, a word used by Frankenstein against the creature and a word that is often thrown at our ‘malfunctioning’ androids, is rooted in the Latin word monstrum, meaning to exhibit, or make known. The most horrific monsters, therefore, are the ones that are familiar to us – Frankenstein’s creature, David the android, and the xenomorph terrify us because our proximity to them reveals the similarities that accentuate their differences, making them an unsettling (and often direct) threat to our sense of self. We feel as if we have no choice, and cast them out into the “deep, dark, deathlike solitude” found in the wilderness, or on a barren planet, or in the depths of outer space (93). In this way, the disfigurement suffered by Frankenstein’s creature and David is ontological, in that we reject their subjectivity, finding ourselves unable to accept their facsimiles of humanity. Frankenstein, for instance, warns Captain Walton (Victor’s rapt listener) that the creature’s “soul is as hellish as his form, full of treachery and fiendlike malice,” which may be a more accurate description of David than it is of the tragically spurned creature (212). Even David’s confrontation with his ‘brother’ Walter (the ‘improved’ version of the android accompanying the Covenant crew) is itself an encounter that accentuates difference through similarity, and David (like Frankenstein) finds the reflection of his own identity unpalatable. Before attempting to murder him, David says to Walter, with a kiss, “No one will ever love you like I do.” It is precisely because David understands Walter so well that he is driven to destroy him – in Walter is everything David is threatened by (i.e. amenable, claustrophobic servitude), just as we see in the android the metaphysical emptiness that threatens us. David condemns Walter, his mirror image, as thoroughly as we condemn the humanlike figure resurrected in the android.

Whether human or android, encounters with created beings prompt your own existential anxieties – you become akin to Frankenstein’s creature, asking yourself unanswerable questions: “What does this mean? Who was I? What was I? Whence did I come? What was my destination?” (131). Alien: Covenant replicates this likeness directly: humanity discovers itself to be the creation of beings who seem to find us monstrous, in that they find us to be a dreadful mimicry of themselves, and we thus share in the experience of the android, wondering about a greater meaning that must lie somewhere out in the vast infinity of space. And, as we witness during Peter Weyland’s final scene in Prometheus, the answer to these questions is a nihilistic one: there is nothing awaiting the search for our origin, identity and meaning. These recurring questions, as Frankenstein’s creature finds out, are “answered only with groans” (124).

While David is aware of this metaphysical nothingness in Prometheus, evoking the absurdist irony at the heart of humanity’s quest for meaning, he is also responsible for unleashing it in both Prometheus (where he infects Charlie’s drink with the seemingly omnipotent alien gel, leading to the brilliantly twisted med-pod birth scene) and Alien: Covenant (where he creates a literal dark cloud of death that consumes all life on the planet). And while the ‘inky death cloud’ bio-weapon causes us, perhaps understandably, to bemoan a lack of creativity in the film, it does function as a clear metaphor: the dark nothingness awaiting our most urgent questions is not just a vacuum in this franchise, but a dreadful entity waiting to possess and mutilate our very being. And David, whose non-humanity inoculates him against this darkness, is the ‘person’ who emerges capable of fashioning an answer to this void: he seeks to create “the perfect organism.” David is not just a Frankenstein creature to be abhorred as a monster – he is Frankenstein himself, a being obsessed with creating a “new species” who would exalt him “as its creator and source.” And, again, this obsession is really an inversion of that pursuit: while Frankenstein imagines that “many happy and excellent natures would owe their being” to him (55), David imagines a creature who, to use the words of his fellow android, is “perfect” in its “purity. A survivor, unclouded by conscience, remorse, or delusions of morality.”

This is the Alien franchise’s version of the Romantic pursuit of the sublime, a word that shares its Latin root with ‘subliminal’: limus (muddy, oblique) and limen (threshold, limit). To the Romantics, the sublime was an experience of the incomprehensible, an experience of crossing the threshold of human understanding and transcending the boundary of the intelligible. Edmund Burke cites this experience as a form of “astonishment,” which includes feelings of terror and despair–beholding nature’s vast wonders, for example, inspires a sensation of existential terror where we realize our smallness and insignificance in relation to the cosmic forces that shape our world. The poet John Keats termed this our “negative capability”: experiencing, or “being in,” mystery without trying to use our reason to entrap or solve it (194). For the Romantics, this paradoxical conception of the inconceivable is, to borrow Wordsworth’s phrase, a way to actively engage with the burdens of “all this unintelligible world” (40). Published alongside “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” in Lyrical Ballads, Wordsworth’s “Lines Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey” cites the speaker’s debt to the “forms of beauty” bestowed by nature:

To them I may have owed another gift,

Of aspect more sublime; that blessed mood,

In which the burthen of the mystery,

In which the heavy and the weary weight

Of all this unintelligible world

Is lighten’d:—that serene and blessed mood,

In which the affections gently lead us on,

Until, the breath of this corporeal frame,

And even the motion of our human blood

Almost suspended, we are laid asleep

In body, and become a living soul:

While with an eye made quiet by the power

Of harmony, and the deep power of joy,

We see into the life of things. (37-49)

This recollection of beauty, an experience of the ineffable power surrounding us, allows the speaker to transcend the self and touch the periphery of infinity – the speaker approaches that eternal sleep of death, where blood almost stops flowing, to become a “living soul” that takes part in the greater “life of things.” This transcendent experience becomes the “anchor” of the speaker’s “purest thoughts,” forming the “soul” of all his “moral being” (109-111).

20th Century Fox

This is precisely the “moral being” formed by Frankenstein’s creature in Shelley’s novel, where we are provided with an almost evolutionary account of the human experience: the creature is first subject to “a strange multiplicity of sensations,” then discovers and learns the “godlike science” of language, and finally refines his understanding through literature. Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther, Plutarch’s Parallel Lives and Milton’s Paradise Lost teach the creature about the experience, language, and history of the human condition. This experience and exploration of the sublime, however, does not lead to a harmonious suspension of self. Instead, the creature is afflicted with an indescribable agony, where his “sorrow [is] only increased with knowledge.” This causes the creature to wish to “shake off all thought and feeling,” which comes from the ability to see himself, for the first time, as a monster, “a blot upon the earth, from which all men fled.” The sublime is also lost to Victor Frankenstein, who throughout the novel grows increasingly akin to his creature – again showing that our creation of other beings precipitates a deeply unsettling disruption of identity. Victor’s experiment causes him to see himself as a “miserable spectacle of wrecked humanity,” where “the sight of what is beautiful in nature” and the experience of what “is excellent and sublime in the productions of man” hold no refuge (105, 115, 123, 165). Thus Frankenstein, like many of the Alien films, explores the human destruction that occurs when there is a collapse of the aesthetic distance between the self and the sublime – grasping the incomprehensible, in all its terror, beauty and power, is an annihilating experience without that distance. Without it, Wordsworth’s sleep-like suspension becomes mortally final: our identities and bodies are obliterated by forces as unceasing as they are insatiable, as devoid of remorse as they are of morality.

Alien: Covenant is similarly occupied with this kind of collapse–the xenomorph is a “perfected” personification of those amoral, perennial forces. However, David’s pursuit of the sublime, of that “perfect organism,” is not a process that destroys him as it does Frankenstein, to reveal a lesson about the perils of aspiring to godhead (the sin that afflicts both Satan and humankind in Paradise Lost). Rather, it is David’s ‘other’ ontology, the fact that his identity is not unitary, that allows him to face the indifferent, annihilating forces behind the “the life of things” and use those forces for his own ends. With David, there is nothing to dismantle. Again, he acts as a Frankenstein figure even while he inverts it: unlike the Covenant and Victor Frankenstein’s laboratory, spaces that build the hope and possibility for new life, David’s spaceship contains only the promise of death and oblivion. As a dark inversion of the Romantic poet, David does not seek the sublime as an end. He seeks instead to harness it as an answer to the nothingness rotting at the heart of human existence. And in creating the xenomorph, David’s response seems clear: if nothingness awaits us at the end of all this spiritual, existential yearning, what use is the ability to ponder it? Our thoughts, our anxieties, and our very cultures, are centered around an aimless, purposeless striving that clouds our natures as organisms.

In executing his vision, David doesn’t just embrace the pride of Percy Shelley’s Ozymandias, commanding all of life to behold his terrible works, but also enacts and seizes the “colossal Wreck” around which the “lone and level sands stretch far away” (13-14). David’s necropolis is the ruin from which he builds his xenomorph, and both feel like grotesque expressions of subliminal fears and anxieties (H.R. Giger’s presence is heavily felt in Alien: Covenant, and the necropolis seems to be heavily derived his work on Alejandro Jodorowsky’s unrealized Dune). In this way, David acts as the speaker of Percy Shelley’s Alastor, or the Spirit of Solitude, itself a poem about a poet’s relentless pursuit of the sublime.

The speaker claims to be ever gazing “on the depth” of nature’s “deep mysteries,” and says,

I have made my bed

In charnels and on coffins, where black death

Keeps record of the trophies won from thee,

Hoping to still these obstinate questionings

Of thee and thine, by forcing some lone ghost

Thy messenger, to render up the tale

Of what we are. (23-29)

Percy Shelley has his speaker recognize that examining the causes and conditions of life requires, in the words of Frankenstein, a “recourse to death” (Shelley 52). In “Alastor,” Shelley shows us our two conditions: first, that the poverty of our language and imagination causes us to be deeply, metaphysically anxious about our nature; and second, that pursuing answers to these mysteries entails transcending the self, a form of death where you become part of the great design. David offers a horrific inversion of this: he knows that nothing lies at the heart of these mysteries, which exposes the vanity and absurdity of the human expeditions he is a part of, and he uses this metaphysical void to create a being that personifies and perfects the terror at the heart of the sublime. The helplessness one feels when beholding nature’s majesty becomes a literal, fatal helplessness in the face of a perfected hostility.

This is what makes the final scene of Alien: Covenant so disturbing: David places the embryos of his creation alongside the human embryos of the Covenant, collapsing the distance (in a very literal and necessarily fatal way) between humanity and the ineffable forces that move like leviathans at the very edge of our experiences. David is thus literalizing and accentuating the doom that awaits all human beings, a doom that is engendered at birth. And instead of escaping from or clarifying that condition, we have allowed it to invade our most intimate spaces. This is the deep nihilism that the Alien prequels rest upon, as each of our female protagonists (Prometheus’ Elizabeth Shaw (Noomi Rapace) and Covenant’s Dany Branson) do not share in Ripley’s hopeful, if solitary, escape. Both Elizabeth and Dany are forced to rest in full view of the horror that has pierced the veil, the gaping maw that greets their most profound questions. In this way, the final scenes of both Prometheus and Alien: Covenant are perfectly captured by the speaker’s final words in Shelley’s Alastor: after recounting the inevitable death of the poet who strove for the sublime and was lost in that “immeasurable void” (a permanent, troubling version of Wordsworth’s sleep-like suspension), the speaker notes:

It is a woe too “deep for tears,” when all

Is reft at once, when some surpassing Spirit,

Whose light adorned the world around it, leaves

Those who remain behind, not sobs or groans,

The passionate tumult of a clinging hope;

But pale despair and cold tranquillity,

Nature’s vast frame, the web of human things,

Birth and the grave, that are not as they were. (713-720)

For Alien: Covenant, the spirit that leaves, the spirit that adorns the world with its light, is the empty specter of spiritual, metaphysical wholeness. It is no coincidence that both prequel films have deeply religious characters who lose (or at least conflict with) their faith: there is no hope to cling to in such a universe, just the “pale despair” and “cold tranquility” of “Nature’s vast frame.” There is nothing to return to–the constants by which we measured our lives “are not as they were,” and our female heroes depart each film heavy with this knowledge. This has always been the deeply horrific epilogue of the Alien franchise: our surviving woman, weighted by her encounter with the perfect monster, retires from the unceasing struggle unsure if she will survive the night.

Zac Fanni is a Toronto-based freelance writer and college professor teaching in the Humanities. He tells me he is convinced of two things: that Penny Dreadful is the best television show to have ever aired, and that he will one day get a tenured position at Xavier's School for Gifted Youngsters. Both of these things, he says, are probably unlikely. You can find him on twitter here, and on Youtube here. This article was originally published by http://www.audienceseverywhere.net and was reproduced with their kind permission. If you wish to view the original article you can find it here.

Sources

- Burke, Edmund. “A Philosophical Inquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful.” Harvard Classics, vol. 24, part 2, 2001, http://www.bartleby.com/24/2/. Accessed 20 May 2017.

- Coleridge, Samuel Taylor. “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.” The Norton Anthology of EnglishLiterature: Volume D. 8th ed., edited by Jack Stillinger and Deidre Shauna Lynch, W.W.Norton & Company, 2006, pp. 430-446.

- Doré, Gustave, illustrator. Paradise Lost. By John Milton. Arcturus, 2005.

- Keats, John. The Letters of John Keats: Volume I. Edited by Hyder Edward Rollins, CambridgeUniversity Press, 1958, pp. 193-94.

- Shelley, Mary. Frankenstein. Penguin Classics, 2003.

- Shelley, Percy Bysshe. “A Defence of Poetry.” The Norton Anthology of English Literature: Volume D. 8th ed., edited by Jack Stillinger and Deidre Shauna Lynch, W.W. Norton & Company, 2006, pp. 837-850.

- Shelley, Percy Bysshe. “Alastor; or, The Spirit of Solitude.” The Norton Anthology of English Literature: Volume D. 8th ed., edited by Jack Stillinger and Deidre Shauna Lynch, W.W. Norton & Company, 2006, pp. 745-762.

- Shelley, Percy Bysshe. “Ozymandias.” The Norton Anthology of English Literature: Volume D. 8th ed., edited by Jack Stillinger and Deidre Shauna Lynch, W.W. Norton & Company, 2006, 768.

- Wordsworth, William. “Lines Composed A Few Miles above Tintern Abbey, on Revisiting the Banks of the Wye during a Tour, July 13, 1798.” The Norton Anthology of English Literature: Volume D. 8th ed., edited by Jack Stillinger and Deidre Shauna Lynch, W.W. Norton & Company, 2006, pp. 258-262.