‘Your sincere admirer’: the Shelleys’ Letters as Indicators of Collaboration in 1821

The Shelleys’ collaborative literary relationship never had a constant dynamic: as with the nature of any human relationship, it changed over time. In Dr. Anna Mercer’s research she aims to identify the shifts in the way in which the Shelleys worked together, a crucial standpoint being that collaboration involves challenge and disagreement as well as encouragement and support. Dr. Mercer suggests despite speculation about an increasing emotional distance between Mary and Percy, the shift in collaboration is not so black-and-white as to reduce the Shelleys’ relationship to one simply of alienation in the later years of their marriage.

INTRODUCTION

This article was originally published on 25 February 2019. It was written prior to the publication of Anna’s book on the subject matter of her essay. The book is every bit as good as I had anticipated and can be purchased directly from the publisher here. Please avoid Amazon at all costs. Another alternative is to simply place the order with your local bookshop. A full review will follow at some point in the future. In the meantime treat this post, and the linked article, as something to whet your appetite.

From the publisher’s description:

How did Percy Bysshe Shelley and Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, two of the most iconic and celebrated authors of the Romantic Period, contribute to each other’s achievements? This book is the first to dedicate a full-length study to exploring the nature of the Shelleys’ literary relationship in depth. It offers new insights into the works of these talented individuals who were bound together by their personal romance and shared commitment to a literary career. Most innovatively, the book describes how Mary Shelley contributed significantly to Percy Shelley’s writing, whilst also discussing Percy’s involvement in her work.

A reappraisal of original manuscripts reveals the Shelleys as a remarkable literary couple, participants in a reciprocal and creative exchange. Hand-written evidence shows Mary adding to Percy’s work in draft and vice-versa. A focus on the Shelleys’ texts – set in the context of their lives and especially their travels – is used to explain how they enabled one another to accomplish a quality of work which they might never have achieved alone. Illustrated with reproductions from their notebooks and drafts, this volume brings Mary Shelley and Percy Bysshe Shelley to the forefront of emerging scholarship on collaborative literary relationships and the social nature of creativity.

And now the original article from 25 February of this year:

2018 was a bad year for the reputation of Percy Shelley (as opposed to the boom year of 2017 about which I wrote in Shelleyan Top Ten Moments - 2017). 2018 was the year we celebrated the bicentennial of Frankenstein. There were conferences, commemorative coins, plays, movies, articles, readings and even biographies. Most of them were truly amazing. For example, the extraordinary, world-wide Frankenreads event staged on Hallowe’en by the Keats-Shelley Association of America (I wrote about that in Frankenstein Is Coming To Your Neighbourhood ). It was truly a joy to see so many people coming together to discover celebrate Mary’s genius. It could also have been used as an opportunity to shine a light on Mary’s collaborator and husband, Percy Shelley. But that did not happen.

The history of Percy’s reception by the pubic has varied widely over the centuries and has been a subject of many a book. Almost unknown during his life, he came to be lionized by the Victorian public for almost all the wrong reasons - presented as a somewhat simpering, juvenile poet who was yet capable of feats of great lyrical accomplishment. This is a false image of Percy that has persisted to this day. Meanwhile the working class has their own version of Shelley - the fire-breathing radical known to Owens, Engels, Ghandi and Marx of whom the latter remarked, “[Shelley] would always have been in the vanguard of socialism”. I wrote about this phenomenon in My Father’s Shelley: A Tale of Two Shelleys. Then came TS Eliot and the New Critics in the early part of the 20th Century. Whether through malice or sheer carelessness these folks focused on the fake Shelley created by the Victorians and set out, consciously and deliberately, to destroy his reputation forever. And they very nearly succeeded. Shelley disappeared from sight for decades. The process of recovery only began in the 1950s and 60s thanks to scholars such as Milton Wilson (with whom I had the luck to later complete my masters at the University of Toronto), the great Kenneth Neill Cameron and Earl Wasserman. The recovery was for the most part limited to the academic setting.

After 2017, there was reason to hope that Percy would re-enter the mainstream with an assist from his now much more famous wife. Such hope was founded on the fact that Percy played a small but universally acknowledged role in the creation of Frankenstein. That we understand his role in the creation of the novel is thanks to the meticulous research of Charles Robinson whose book The Original Frankenstein (Penguin Random House) was published with the byline: “Mary Shelley with Percy Shelley”. Perhaps, I had hoped, by shining a light on this fact, we might be able to lead the public to a better understanding of his own profound contributions to our culture. Alas no, and in some cases the portrait that was created in 2018 of Percy departs so far from the truth as to be laughable - as in the case of Haifaa al Mansour’s lamentable teen-angst bio-pic Mary Shelley. I reviewed this movie in my post, The Truth Matters. Those who have had the misfortune of watching this movie may have noticed that I have taken one of the stills from the movie to use as the background to the title page of my post. This image which shows Mary and Percy actually in love with one another may be one of the only accurate details from the entire movie.

Anna Mercer, on the other hand, is an expert a relatively new field: understanding the extent of the collaborative literary relationship that existed between Percy and Mary from their initial meeting in 1814 through to Percy’s death in 1822, as well as considering Mary’s later work. Dr. Mercer is about to publish a book (with Routledge) that aims to identify the textual connections between the works of the two authors, considering the Shelleys’ relationship in terms of literary and stylistic ideas, as opposed to purely biographical studies.

What follows will offer you an insight into her incisive and fascinating work. I can’t wait for the book.

‘Your sincere admirer’: the Shelleys’ Letters as Indicators of Collaboration in 1821 — by Dr. Anna Mercer

The Shelleys’ collaborative literary relationship never had a constant dynamic: as with the nature of any human relationship, it changed over time. In my research I aim to identify the shifts in the way in which the Shelleys worked together, a crucial standpoint being that collaboration involves challenge and disagreement as well as encouragement and support. The Shelleys’ collaborative peak was the work on Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein in 1816-1818 (to which Percy Shelley made corrections and alterations). Interest in the Shelleys’ relationship post-1818 suggests that they were not working as closely in the four years immediately preceding Percy’s death in 1822. Fascinating and insightful biographies of the couple, such as Daisy Hay’s Young Romantics, suggest that Mary worked alone on her novel Valperga (published in 1823), and Percy increasingly engaged in literary discussions with others. Evidence for this is in part based on the significance of Percy’s 1821 semi-autobiographical poem Epipsychidion, ‘an idealised history of my life and feelings’,[1] which not only contains a thinly-veiled criticism of Mary’s character, but is in many ways a love poem addressed to another woman, Emilia Viviani. Percy actively hid the poem from Mary. She did not fair copy the poem, and it arrived at the publishers in Percy’s own hand; this is unusual in that Mary was Percy’s ‘usual copyist’.[2] Daisy Hay writes of the Shelleys in 1821:

Shelley’s interest in Emilia slowly waned over the course of 1821 and dissipated by the time of her marriage to an Italian nobleman in September of that year. But the interlude widened the developing rift between Shelley and Mary, and made her more cautious in both her emotional and her intellectual engagement with him.[3]

However, despite this suggesting that the creative process of composition becomes something Percy hides from Mary, I want to suggest that the shift in collaboration is not so black-and-white as to reduce the Shelleys’ relationship to one simply of alienation in the later years of their marriage. One step towards doing this is to consider the Shelleys’ extant letters to each other in these later years. This blog focuses in particular on the letters of 1821 in order to support my suggestion.

Percy Shelley by Amelia Curran. National Portrait Gallery.

Percy’s letters to Mary show a keen intellectual interest in the progress of written work, the potential growth of his own mind, and Mary’s development as a novelist. Entangled within this are demonstrations of remarkable intimacy and tenderness. It is the combination of intellect and genuine affection that marked the Shelleys’ relationship from their initial meeting and dramatic elopement in 1814. A letter from Percy to Mary in July 1821, shows this combination of love and intellectual musings:

My dearest love – […] I spent three hours this morning principally in the contemplation of the Niobe, & of a favourite Apollo; all worldly thoughts & cares seem to vanish from before the sublime emotions such spectacles create: and I am deeply impressed with the great difference of happiness enjoyed by those who live at a distance from these incarnations of all that the finest minds have conceived of beauty, & those who can resort to their company at pleasure. What should we think if we were forbidden to read the great writers who have left us their works. – And yet, to be forbidden to live at Florence or Rome is an evil of the same kind & scarcely of less magnitude. […] Kiss little Babe, and how is he – but I hope to see him fast asleep to-morrow night. – And pray dearest Mary, have some of your Novel prepared for me for my return.[4]

Percy’s ekphrastic descriptions of his reaction to the statues in the Uffizi Palace, Florence are divulged to Mary here in detail. Beyond expecting Mary to understand this response to such artwork, the consideration of the sculptures in Italy is meant to conjure up for his wife a sense of shared experience: they had been living in the country since 1818 and had been on travels together in Europe since the year that they met. In describing his pleasure of experiencing Italy, Percy conveys to Mary his satisfaction in their living there, crucially in relation to the intellectual stimulation it offers, and in turn more subtly by implying her presence there adds to this satisfaction. Percy shows affection for his young son (something he is often criticised for failing to do) and signs off the letter by reminding Mary of her own toil in literature: the anticipation of her novel, Valperga, implies Percy’s interaction with Mary on this work, too. Another letter from Percy to Mary dated August 10th 1821 explores Percy’s interest in Mary’s work:

How is my little darling? And how are you, & how do you get on with your book. Be severe in your corrections, & expect severity from me, your sincere admirer. – I flatter myself you have composed something unequalled in its kind, & that not content with the honours of your birth & your hereditary aristocracy, you will add still higher renown to your name.[5]

Percy is at once concerned with his wife’s progress in writing: ‘expect severity from me’ implies Percy will be critiquing the work. Yet he is also her ‘sincere admirer’ and sees her future legacy as something dependent on her own genius and not just because of her famous literary parents, William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft.

Mary Shelley by R. Rothwell. National Portrait Gallery.

Unfortunately there is only one extant letter from Mary Shelley to Percy Shelley written in 1821. However, also in 1821 Mary Shelley writes a postscript on Percy’s letter to Thomas Love Peacock on March 21st showing a shared intimacy in communication with others. Likewise, Percy completes Mary’s letter to Claire Clairmont a few days later in April.[6] The one letter from Mary to Percy we have from this particular year is less concerned with intellectual affairs but shows the Shelleys’ reliance on one another in a time of crisis. Following the discovery of the ‘Hoppner scandal’, in which the Shelleys were accused of various wrongdoings (the complex details of which I cannot explore fully here, but are well worth reading up on; this is an intriguing unsolved mystery in the Shelleys’ biography), Mary Shelley writes to her husband:

Shocked beyond all measure […] I wrote to you with far different feelings last night – beloved friend – our bark is indeed tempest tost but love me as you have ever done & God preserve my child to me and our enemies shall not be too much for us.[7]

This letter explicitly recalls a much earlier letter written by Mary in 1814 to Percy:

we will defy our enemies & our friends (for aught I see they are all as bad as one another) and we will not part again.[8]

This shows a united front and a defiance that prevails in the Shelleys’ relationship: Mary sees ‘enemies’ as something to be challenged by the Shelleys as a couple, in both 1814 and 1821.

The Grave of Percy Shelley, Non-Catholic Cemetery, Rome.

However, there is evidence elsewhere that intellectual discussions remained a primary concern for Mary in 1821. Mary Shelley writes to Maria Gisborne in November: ‘Do you hear anything of Shelley’s Hellas?’ Hellas was completed by Percy in late October, and is one of the few works of Percy Shelley’s to be published in his lifetime (it was published in February 1822). Although, like Epipsychidion, the manuscript fair copy of Hellas wasn’t sent to the publishers in Mary’s hand,[9] the inclusion of Mary’s queries on the work in this letter show her awareness and possible involvement in the toil required in order to bring this poem to press. In this letter to Maria Gisborne from 1821 Mary also writes: ‘Ollier [the Shelleys’ publisher in England] treats us abominably – I should much like to know when he intends to answer S-’s last letter concerning my affair. I had wished it to come out by Christmas – now there is no hope.’[10] The Shelleys’ literary affairs – in Italy where composition occurs, and back in London where they attempt to publish – are as entangled as ever.

Perhaps most telling in Mary’s letter to Maria Gisborne is the wistful sentence: ‘If Greece be free, Shelley and I have vowed to go, perhaps to settle there, in one of those beautiful islands where earth, ocean, and sky form the Paradise’. Written in November 1821, how strongly this recalls Percy Shelley’s own letter to his wife on 16th August 1821 expressing the wish to relocate to a remote island paradise:

My greatest content would be utterly to desert all human society. I would retire with you & our child to a solitary island in the sea, would build a boat, & shut upon my retreat the floodgates of the world. – I would read no reviews & talk with no authors. – If I dared trust my imagination, it would tell me that there were two or three chosen companions beside yourself whom I should desire. – But to this I would not listen. – Where two or three are gathered together the devil is among them, and good far more than evil impulses – love far more than hatred – has been to me, except as you have been it’s object, the source of all sorts of mischief. So on this plan I would be alone & would devote either to oblivion or to future generations the overflowings of a mind which, timely withdrawn from the contagion, should be kept fit for no baser object.[11]

The Grave of Mary Shelley, The Parish Church of St Peter, Bournemouth.

END NOTES

[1] P B Shelley, The Letters of Percy Bysshe Shelley Vol. II ed. by Frederick L. Jones (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1964) 18 June 1822, p. 434.

[2] Newman Ivey White, Shelley Vol II (London: Secker and Warlburg, 1947), p. 255.

[3] Daisy Hay, Young Romantics (London: Bloomsbury, 2010), p. 206.

[4] P B Shelley, Letters Vol II 31st July 1821, p. 313,

[5] P B Shelley, Letters Vol II 10th August 1821, p. 324.

[6] Mary W Shelley, The Letters of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (3 vols) Vol I ed. by Betty T. Bennett (London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1980 repr. 1991), pp. 186-187.

[7] Mary W Shelley, Letters Vol I, p. 204.

[8] Mary W Shelley, Letters Vol I, p. 5.

[9] It was in the hand of Edward Williams.

[10] Mary W Shelley, Letters Vol I, p. 209.

[11] P B Shelley, Letters Vol II 15 August 1821, p. 339.

[12] Mary W Shelley, Letters Vol I, p. 210.

[13] Mary W Shelley, Letters Vol I, p. 450.

This article was originally published in Romantic Textualities: Literature and Print Culture, 1780–1840 on 8 June 2015. It was published under a Creative Commons licence pursuant to which “all content is available without charge to the user or his/her institution. You are allowed to read, download, copy, distribute, print, search or link to the full texts of the articles in this journal without asking prior permission from either the publisher or the author.”

More about the Journal: “Romantic Textualities: Literature and Print Culture, 1780–1840 is an open-access journal that is committed to foregrounding innovative Romantic-studies research into bibliography, book history, intertextuality, and textual studies. To this end, we pubRomanticlish material in a number of formats: peer-reviewed articles, reports on individual/group research projects, bibliographical checklists, biographical profiles of overlooked Romantic writers and book reviews of relevant new research. Find out more by clicking here.”

Frankenstein, a Stage Adaptation. Review by Anna Mercer

The last stage production of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein I saw was a wonderful experience. The Royal Opera House’s ballet version of the novel was captivating and reflected the text’s themes of pursuit and terror with a striking intensity.[i] I’m always wary of adaptations of things I love, but after my positive experience at the ballet in London, I decided to go along to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein when I was visiting New York. This new production by Ensemble for the Romantic Century was held in the Pershing Square Signature Center, a lovely venue. But the play itself was a disappointment overall, with only a few redeeming features.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Directed by Donald T. Sanders. A Production of Ensemble for the Romantic Century. Performed at the Irene Diamond Stage at the Pershing Square Signature Center, New York City.

A review by Anna Mercer.

The last stage production of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein I saw was a wonderful experience. The Royal Opera House’s ballet version of the novel was captivating and reflected the text’s themes of pursuit and terror with a striking intensity.[i] I’m always wary of adaptations of things I love, but after my positive experience at the ballet in London, I decided to go along to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein when I was visiting New York. This new production by Ensemble for the Romantic Century was held in the Pershing Square Signature Center, a lovely venue. But the play itself was a disappointment overall, with only a few redeeming features.

The Royal Opera's adaptation of Frankenstein, which ran from 2015-16.

One of the many differences between this play and the ballet was the inclusion of Mary Shelley herself as a character. It is always exciting to hear Mary Shelley’s words read aloud on stage, and in this case it was not just the text of her “hideous progeny,” but also excerpts from her letters and journals that were dramatized onstage. However, there were some strange modifications. The composition of the novel is moved to 1819. This is clearly because those behind the production had chosen to emphasise that famous interpretation of Frankenstein as a thinly-veiled account of Mary Shelley’s grief at the loss of her young children. Such readings are outdated and limited, but they create tension and emotion onstage, something played to full effect here by the actors (who, incidentally, use American accents). Other reviewers also disliked the representations of Mary Shelley and Percy Bysshe Shelley – The New York Times critic Laura Collins-Hughes wrote that “Mia Vallet’s Mary and Paul Wesley’s Percy are jarringly contemporary in affect and lack a vital spark.”[ii]

Moreover, the play – as sadly seems to be the norm in dramatisations of the Shelleys’ lives – pits Percy and Mary against each other. This seems to be for two reasons. Firstly, the tension creates “comic” effect; secondly, it works to champion Mary as a hidden genius underappreciated by her husband. Mary is trying to write, but is visibly exasperated by the comments made by Percy. There is some truth in this – he did suggest adding more polysyllabic, Latinate terms to the Frankenstein manuscript, as you can see for yourself by visiting the (free) online Shelley-Godwin Archive.[iii] However, Mary’s eye-rolling in this scene is added for dramatic effect; the writer/director encourages the audience’s laughter because of her exasperation. We are meant to see Percy’s suggestions as unhelpful, to Mary, to anyone. The lack of any mention of Percy’s literary achievements (besides some short lyrics – none of the longer, philosophical poems) makes his input seem even more arrogant. The play seeks a cheap laugh by entreating a modern audience to mentally respond with: “that’s no improvement! What a pompous guy that Shelley is.”

From "Mary Shelley's Frankenstein," which ran at the Irene Diamond Stage until January 7.

The result is a negative image of both authors. Although space does not permit me to explain more here, most Shelley scholars now agree that Mary and Percy were two participants in a reciprocal collaborative exchange. Mary Shelley invited Percy’s comments on Frankenstein, her first novel. Seek out the work of Charles E. Robinson, a late English Professor who knew the Frankenstein manuscripts better than anyone, and you will find that his commentary explains the two-way creative discussions that went into producing the text.[iv] Percy’s alterations were accepted and included by Mary and they appear in the final published version. As such, any implication that Mary disapproved of his involvement is condescending to her, as it paints her as a pushover and a victim. In presenting Percy as a patronising partner to Mary, the play actually ends up patronising Mary herself.

The National Theatre's stage production of Frankenstein premiered in 2011.

Mary’s father William Godwin is similarly represented as a bully. However, there were some positive aspects of the production as a whole: the set was gorgeous and complex (I speak as someone with no experience in theatre production and set design, I might add!), and the Creature – as is often the case – steals the show. Robert Fairchild’s writhing movements onstage were striking, and his performance was clearly very much influenced by the Danny Boyle production at the National Theatre with Jonny Lee Miller and Benedict Cumberbatch. The score – including works by Liszt, Bach, and Schubert on oboe, piano, organ, and harpsichord – and Fairchild’s obvious talent as a dancer made certain scenes from the novel a real success. The mezzo soprano (Krysty Swann) was also a delight.

I understand that tension and misery of experience, including death and isolation, create more drama for a theatre production than an account of the social nature of creativity or the true story behind the genesis of one of the greatest novels in English literature. But I am disappointed by this work of art that ends up crippling another work of art. Those who are unfamiliar with Mary’s oeuvre and talents would leave misinformed and uninterested. For Mary Shelley fans, there were no new insights here, nor was it particularly enjoyable. The focus on Frankenstein and literally nothing else she ever wrote (besides her letters and journals) is becoming perhaps a little tiring, but I hope such a trend is peculiar to this bicentenary year, and that things might improve in the future.

Footnotes

[i] For more on the Royal Opera’s adaptation of Frankenstein, see my review here.

[ii] You can find the New York Times’ full review here.

[iii] Find this excellent archive here.

[iv] Professor Robinson’s long list of books includes an edition of Frankenstein manuscripts, entitled The Frankenstein Notebooks and The Original Frankenstein. You can find an excellent version of Frankenstein, with an introduction written by Robinson, here – but please, buy it from your local bookstore!

Anna Mercer completed her PhD on the collaborative literary relationship of Percy Bysshe Shelley and Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley at the University of York in 2017. She has also studied at the University of Cambridge (Jesus College) and the University of Liverpool. She currently works at Keats House, Hampstead and as the Director of Communications for the Keats-Shelley Association of America. Her first monograph will be published by Routledge in 2019. She is on Twitter (@annamercer_) and you can visit her blog here:

Why the Shelley Conference? By Anna Mercer

The Shelley Conference takes place in London at Institute for English Studies on the 15th and 16th of September. The keynote speakers are Prof. Nora Crook, Prof Kelvin Everest and Prof. Michael O’Neill. The conference is open to everyone - which is just how Shelley would have liked it. He would have also liked the fact that he and his wife are treated as co-equals and creative collaborators. I myself am honoured to be part of the conference and will be speaking on what I call "Romantic Resistance" - Shelley's strategies for opposing political and religious tyrannies. They are surprisingly applicable to our times! Here is co-organizer Anna Mercer on how this amazing conference came

The Shelley Conference takes place in London at Institute for English Studies on the 15th and 16th of September.

The keynote speakers are Prof. Nora Crook (Anglia Ruskin University), Prof Kelvin Everest (University of Liverpool) and Prof. Michael O’Neill (Durham University). The conference is open to everyone - which is just how Shelley would have liked it. He would have also liked the fact that he and his wife are treated as co-equals and creative collaborators. I myself am honoured to be part of the conference and will be speaking on what I call "Romantic Resistance" - Shelley's strategies for opposing political and religious tyrannies. They are surprisingly applicable to our times! Here is co-organizer Anna Mercer on how this amazing conference came to be:

Why the Shelley Conference? By Anna Mercer

Anna Mercer

I was motivated to create ‘The Shelley Conference 2017’ because of my own frustration with the fact that there is no regular event, academic or otherwise, dedicated solely to the study of Percy Bysshe Shelley’s works. Neither is there such an event for Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley. The other Romantics enjoy fantastic annual symposiums where experts and lovers of great literature meet; for example I have been lucky enough to attend the Keats Conference in Hampstead and the Coleridge Conference in the South West (held in Bristol, or Somerset). These carefully planned gatherings of world-renowned speakers and literature enthusiasts include walks and other activities in the surroundings loved by Keats and Coleridge. They encourage postgraduate participation, and are jovial and create a sense of community. I know there is also a similar event for Wordsworth in Grasmere; why is there no such event for PBS or MWS?

My research (on the collaborative literary relationship of PBS and MWS) led me to develop the idea of a conference that celebrated both authors. Contemporary criticism thankfully no longer wastes time belittling MWS as minor in comparison to PBS’s genius, or depicting PBS as a tyrannical, corrupt editor of her work. The birth of ‘The Shelley Conference’ was set to chime with this refreshing lack of conflict in contemporary study, something that I admit my work in particular seeks to broaden and develop, particularly through the use of manuscript evidence, in order to understand how the Shelleys worked in a reciprocal literary exchange.

The Shelleys in popular culture, however, remain separated and many misconceptions about their relationship persist in the public consciousness (see for example my review of ‘The Secret Life of Books: Frankenstein’ broadcast on BBC4). I have become increasingly aware that now such Shelley-related events are not limited to a small group of academics, and with social media and the help of other Shelley platforms (including this one!), the Shelleys can be identified for what they are actually are, and what they actually sought to represent: that is, two incredibly talented authors, who dedicated their lives to the study and writing of radical and innovative literature.

The Shelley of the conference title remains ambiguous. Furthermore, I have clearly stated that the conference is two days on the works of PBS and MWS. Our speakers will pay attention to biographical details in order to gauge how their shared lives (and also their shared travels) influence their texts, as opposed to the texts revealing truths about their lives. Can we remove the damaging opinion that the Shelleys’ relationship was something defined by scandal, infidelity, gossip, and anti-establishment teenage pursuits? They certainly would have wished we could do so. Let us return to their writings, and not the many, many biographical speculations created by scholars and other writers, some with good intentions, some without.

It is for this reason that I am delighted to announce the breadth of papers that we have at the conference. We have panels that address philosophy, translation, the reception of these authors, editing, the Shelleys in Italy, the Shelleys and science, radical Shelley (including Graham Henderson’s paper on ‘Romantic Resistance’), utopia and dystopia, and even the Shelleys’ diets. We have speakers from all over the world including Canada and mainland Europe, and we have postgraduates speaking at various stages in their career, as well as more established academics, and other writers: novelists, independent scholars, and poets. Some panels include papers on PBS and MWS side-by-side, others focus solely on one author, with the presumption that the Q&A discussion at the end of the presentations will be broad and energetic, reaching into different spheres of knowledge, and addressing the wider Shelley circle – for example Peacock, Hogg, Claire Clairmont, the Gisbornes, and Byron.

Also, excitingly it is now, in the first part of the 21st century, that the most detailed comprehensive editions of PBS’s works are in production (The Complete Poetry of Percy Bysshe Shelley ed. Donald Reiman, Neil Fraistat and Nora Crook is already well advanced, with Vol VII published soon, and The Poems of Shelley ed. Kelvin Everest, G. M. Matthews, Michael Rossington and Jack Donovan is nearing completion). Michael Rossington and Nora Crook will deliver short presentations on the progress of these editions in an optional session during the lunch break on Friday.

I would like to add that I am indebted to Kelvin Everest, an academic mentor to me since my undergraduate days. He was the pioneer of the first Shelley conferences in Gregynog, and his collection of essays that came from that time can be found here. I am honoured to say that he has been an invaluable advisor to me during this conference, and will also be delivering a keynote lecture, alongside the other plenary talks by Michael O’Neill and Nora Crook.

I also thank Michael Rossington, who similarly has delivered advice and guidance, and my coorganiser Harrie Neal (she speaks on Saturday, with a paper on ‘Mary Shelley’s post-capitalist ecology’).

See the detailed programme here.

Thank you to our sponsors – who, amongst other things, have made it possible for us to charge the reduced fee of £15 only for postgraduates and unwaged delegates:

Thanks also to the support from our host institution, the Centre for Eighteenth Century Studies (CECS) at the University of York, and our venue, the Institute for English Studies (IES) in London.

I sincerely hope that the Shelley Conference may occur again in years to come – watch this space.

In the Footsteps of Mary and Percy Shelley. By Anna Mercer

One of the great things about studying Shelley is where it can take you if you are intrepid. In the course of his short life he traveled to Ireland, Wales, Scotland, Devon, France, Switzerland and Italy - and some of the places he visited are among the most sublime and picturesque in Europe. Join Anna Mercer for a trip to Shelley's Mont Blanc!

My Guest Contributor series continues with another travel feature by Anna Mercer. Anna as readers of this space will known has studied at the University of Liverpool and the University of Cambridge. She is now in completing her thesis as an AHRC-funded doctoral candidate at the Centre for Eighteenth Century Studies, University of York. Her research focuses on the collaborative literary relationship of Percy and Mary Shelley. She won the runner-up Keats-Shelley Prize in 2015 for her essay on the Shelleys, which was published in the Spring 2016 issue of the Keats-Shelley Review. A new article on this subject is due to appear in the forthcoming issue of the same magazine.

One of the great things about studying Shelley is where it can take you if you are intrepid. In the course of his short life he traveled to Ireland, Wales, Scotland, Devon, France, Switzerland and Italy - and some of the places he visited are among the most sublime and picturesque in Europe. I have an important trip planned to Lerici in Italy where he died and have both written and audio-visual material planned for publication in May.

In the meantime enjoy Anna's record of her visit to Geneva and Chamonix. I myself made this trip and I can tell you it is absolutely stunning at any time of the year. You can watch my VLOG about my visit to the Villa Diodati here.

In June 2016 I made a pilgrimage to an area in Europe known for its sublime scenery. I have read so much about the snowy peaks of the Alps and the shores of Lake Geneva, primarily from two sources that figure in my life because of my PhD research at the University of York. I am studying Percy Bysshe Shelley and Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, two Romantic authors who, before their marriage but after their romantic union, spent the summer in the environs of Geneva and Chamonix in 1816, exactly 200 years before I arrived there.

Percy Shelley had originally thought of leaving England for Italy. The Shelleys were instead convinced to head to Cologny near Geneva by their travellng companion Claire Clairmont, Mary’s step-sister, who in London had begun an affair with Lord Byron.

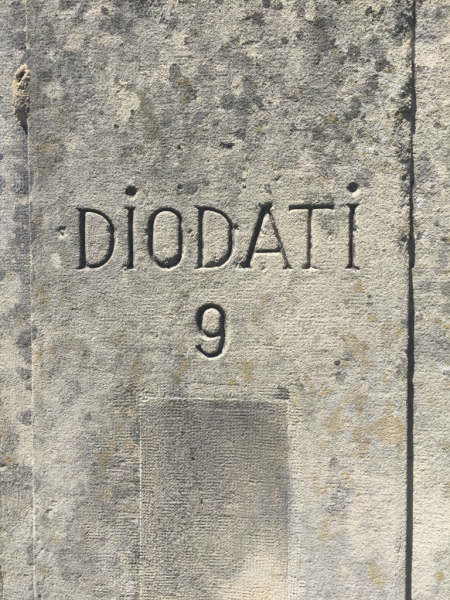

On 13 May 1816 the Shelleys and Claire arrived in Geneva, followed on 25 May by Byron and his physician Dr. John Polidori. By June, both parties had taken residences close to each other on the shores of the lake; Byron stayed at the Villa Diodati. Incessant rain often prevented them from going out on the water in the evenings, and even stopped Percy, Mary and Claire from returning to their own lodgings.[1] The eruption of Mount Tambora in 1815 has devastated the weather across Europe, and 1816 is recalled now as ‘the year without a summer’.

I also arrived to an atmospherically rainy Geneva:

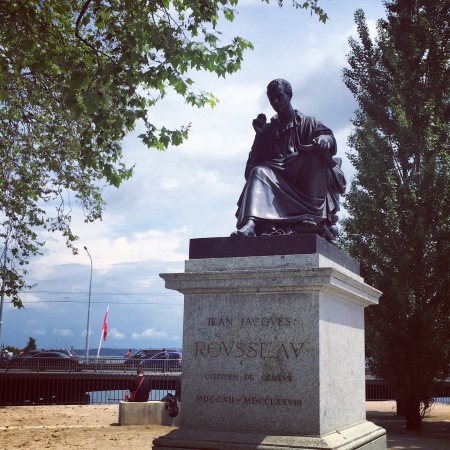

The weather eventually cleared, and we explored the town. Like the Shelleys, we were intrigued by the literary greats who had graced the city, among the Rousseau.

During the 1816 summer, Percy, Mary and Claire stayed at Maison Chapuis but often spent time at Byron’s grander lodgings nearby. Geneva is where Mary Shelley began writing her most famous and enduring novel, Frankenstein (first published in 1818). Mary’s terrifying novel – according to her 1831 introduction – was ostensibly inspired by a ‘waking dream’ she had after hearing Percy and Byron’s discussions on ‘the nature of the principle of life’ to which she ‘was a devout but nearly silent listener’. This account of her literary genius is characteristically modest, as her silence is in all likelihood overplayed; the community at Geneva in 1816 offered a stimulating intellectual environment and Percy and Mary collaborated on the novel as well as many other works.

Mary began writing Frankenstein in June 1816. The Shelleys met Byron on 27 May, and he took up residence at Diodati on 10 June, and by June 22 Percy Shelley and Byron went on a tour of Lake Geneva together. So, although Mary only recorded the composition of Frankenstein in her journal in July, it is likely the novel was started between 10-22 June.[2]

In a previous post here at www.grahamhenderson.ca, I reviewed the excellent exhibition on Frankenstein at the Bodmer Foundation Library and Museum: Frankenstein: Creation of Darkness. We were treated with a walk around the grounds of the Villa Diodati itself.

Percy and Mary included descriptions of their travels in the 1817 publication History of a Six Weeks’ Tour. Mary’s view of Geneva was muted to say the least:

There is nothing […] in it that can repay you for the trouble of walking over its rough stones. The houses are high, the streets narrow, many of them on the ascent, and no public building of any beauty to attract your eye, or any architecture to gratify your taste. The town is surrounded by a wall, the three gates of which are shut exactly at ten o’clock, when no bribery (as in France) can open them (101-2).

However, the dramatic weather offered her respite:

The lake is at our feet, and a little harbour contains our boat, in which we still enjoy our evening excursions on the water. Unfortunately we do not now enjoy those brilliant skies that hailed us on our first arrival to this country. An almost perpetual rain confines us principally to the house; but when the sun bursts forth it is with a splendour and heat unknown in England. The thunder storms that visit us are grander and more terrific than I have ever seen before. We watch them as they approach from the opposite side of the lake, observing the lightning play among the clouds in various parts of the heavens, and dart in jagged figures upon the piny heights of Jura, dark with the shadow of the overhanging cloud, while perhaps the sun is shining cheerily upon us. One night we enjoyed a finer storm than I had ever before beheld. The lake was lit up—the pines on Jura made visible, and all the scene illuminated for an instant, when a pitchy blackness succeeded, and the thunder came in frightful bursts over our heads amid the darkness (99-100).

I am particularly fascinated by this jointly-authored publication History of a Six Weeks’ Tour, Mary’s first foray into print (besides her early light verses published in her father’s library). The text of this volume is an intermingling of voices, the provenance of each section being drawn from a joint journal, numerous letters and original words composed for the edition. I will be discussing the History in a paper at the British Association for Romantic Studies conference in York in July, 2017.

On our first day in Geneva, after wandering around and dodging the rain, we immediately set off to cross the border. We were staying in an idyllic, isolated chalet in France, and the first place we wanted to visit the next day was the site of many inspirations for both Percy and Mary: the town of Chamonix, which rests under the imposing gaze of Mont Blanc, Europe’s highest peak.

Our travels from Geneva to the French Alps reminded me of Mary Shelley’s third novel, The Last Man (1826), in which the protagonist Lionel and his companion Adrian (a Percy Shelley-esque figure) make a similar trajectory:

We left the fair margin of the beauteous lake of Geneva, and entered the Alpine ravines; tracing to its source the brawling Arve, through the rock-bound valley of Servox, beside the mighty waterfalls, and under the shadow of the inaccessible mountains, we travelled on; while the luxuriant walnut-tree gave place to the dark pine, whose musical branches swung in the wind, and whose upright forms had braved a thousand storms – till the verdant sod, the flowery dell, and shrubbery hill were exchanged for the sky-piercing, untrodden, seedless rock, “the bones of the world, waiting to be clothed with every thing necessary to give life and beauty”** Mary Wollstonecraft’s Letters from Norway.

This excerpt concludes with a quotation taken from Mary Shelley’s mother, Mary Wollstonecraft. Her Letters written during a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway and Denmark inspired Mary in her own travel writing. This was a text in which the author sought ‘to let my remarks and reflections flow unrestrained’ (Advertisement). The writing of Mary Shelley’s radical parents (her father was William Godwin) were some of the texts the Shelleys were both reading – occasionally aloud together – in 1814, the year of their elopement, and their first journey to the continent. Texts included Letters written during a Short Residence by Wollstonecraft and Caleb Williams by Godwin.[3]

On the day of our arrival in Chamonix, the mountains were not only seemingly inaccessible, but invisible. Low cloud prevented us from identifying Mont Blanc above us, but did not damage the charming nature of the town, now a popular ski-resort, and the drive into the Valley was still dramatic:

Despite the cloud, we decided to get the train to the ‘Mer de Glace’. Perhaps bad weather would have prevented tourists from making the journey in the Shelleys’ day, but in 2016 the Montenvers Railway (opened 1909) takes you right up to the viewing platform.

On arrival, we were sorely disappointed, as we couldn’t see a thing. Mildly upset that we had traveled all this way up and wouldn’t see the glacier itself, my companion convinced me to take the cable car that descends into the mist despite the slightly miserable conditions.

When we landed at the bottom, the glacier was in full view. I will firstly give you Percy Shelley’s description of this natural wonder:

We have returned from visiting the glacier of Montanvert, or as it is called, the Sea of Ice, a scene in truth of dizzying wonder. The path that winds to it along the side of a mountain, now clothed with pines, now intersected with snowy hollows, is wide and steep. […] We arrived at Montanvert, […] On all sides precipitous mountains, the abodes of unrelenting frost, surround this vale: their sides are banked up with ice and snow, broken, heaped high, and exhibiting terrific chasms. The summits are sharp and naked pinnacles, whose overhanging steepness will not even permit snow to rest upon them. Lines of dazzling ice occupy here and there their perpendicular rifts, and shine through the driving vapours with inexpressible brilliance; they pierce the clouds like things not belonging to this earth. The vale itself is filled with a mass of undulating ice, and has an ascent sufficiently gradual even to the remotest abysses of these horrible desarts. It is only half a league (about two miles) in breadth, and seems much less. It exhibits an appearance as if frost had suddenly bound up the waves and whirlpools of a mighty torrent. We walked some distance upon its surface. The waves are elevated about 12 or 15 feet from the surface of the mass, which is intersected by long gaps of unfathomable depth, the ice of whose sides is more beautifully azure than the sky. In these regions every thing changes, and is in motion. This vast mass of ice has one general progress, which ceases neither day nor night; it breaks and bursts for ever: some undulations sink while others rise; it is never the same. The echo of rocks, or of the ice and snow which fall from their overhanging precipices, or roll from their aerial summits, scarcely ceases for one moment. One would think that Mont Blanc, like the god of the Stoics, was a vast animal, and that the frozen blood for ever circulated through his stony veins.We dined (M***, C***, and I) on the grass, in the open air, surrounded by this scene. The air is piercing and clear. We returned down the mountain, sometimes encompassed by the driving vapours, sometimes cheered by the sunbeams, and arrived at our inn by seven o’clock (History of a Six Weeks’ Tour, 164-168).

However, we were not just relieved to be able to see more than cloud, but shocked by the lack of glacier before us.

Carl Hackert, ‘Vue de la Mer de Glace et de l’Hôpital de Blair’ (1781) (Centre d’iconographie genevois).

Percy Shelley’s premonition that Buffon’s ‘sublime but gloomy theory’ that ‘this globe which we inhabit will at some future period be changed into a mass of frost’ (161-2), was entirely unfounded. We knew that the ice was melting – the majority of us do (I am avoiding any political comment here) – but we were still affected by this huge difference across the decades. You can read more on this subject at the British Romantic Writing and Environmental Catastrophe website, an AHRC-funded project at the University of Leeds.

You can now go inside the glacier itself:

When we went back up in the cable car, the clouds had cleared and we had an astounding view of the Mer de Glace and surrounding peaks. This reminded me of Volume II, Chapter II of Frankenstein, as Victor makes the same ascent. He makes it alone, because ‘the presence of another would destroy the solitary grandeur of the scene’. Just as in our visit, in the novel the clouds clear from the protagonist around midday:

It was nearly noon when I arrived at the top of the ascent. For some time I sat upon the rock that overlooks the sea of ice. A mist covered both that and the surrounding mountains. Presently a breeze dissipated the cloud, and I descended upon the glacier.From the side where I now stood Montanvert was exactly opposite, at the distance of a league; and above it rose Mont Blanc, in awful majesty. I remained in a recess of the rock, gazing on this wonderful and stupendous scene. The sea, or rather the vast river of ice, wound among its dependent mountains, whose aerial summits hung over its recesses. Their icy and glittering peaks shone in the sunlight over the clouds. My heart, which was before sorrowful, now swelled with something like joy.

On our way back to Chamonix, we had the same luck again – an overwhelming sight.

We returned two days later in marginally better weather to take the cable-car that made the ascent of Mont Blanc itself. To be honest, the cloud had left me confused as to where the peak of this infamous mountain was.

A ride up the side of the mountain to the Aiguille Du Midi took my breath away. This trip is a must for any visitor to the area. We were warned that the visibility would be bad at the top, but when we arrived the clouds cleared and left us with spectacular views. If you are a lover of the Shelleys, you will be further mystified in wondering just what those two incredible authors would have made of the sight, if they could have ascended to 3,842m and see the ‘vast animal’ Mont Blanc this close.

Mont Blanc appears in both of the Shelleys’ works (such as Mary’s Frankenstein and The Last Man), but it is Percy Shelley’s poem dedicated to the mountain that reveals the full extent of their awe. You can read the full poem here, but I will leave you with its final lines:

Mont Blanc yet gleams on high:—the power is there,

The still and solemn power of many sights,

And many sounds, and much of life and death.

In the calm darkness of the moonless nights,

In the lone glare of day, the snows descend

Upon that Mountain; none beholds them there,

Nor when the flakes burn in the sinking sun,

Or the star-beams dart through them:— Winds contend

Silently there, and heap the snow with breath

Rapid and strong, but silently! Its home

The voiceless lightning in these solitudes

Keeps innocently, and like vapour broods

Over the snow. The secret strength of things

Which governs thought, and to the infinite dome

Of heaven is as a law, inhabits thee!

And what were thou, and earth, and stars, and sea,

If to the human mind’s imaginings

Silence and solitude were vacancy?

This article is reprinted with the kind permission of the author. It originally appeared 6 February 2017 on her excellent blog which you can find here.

[1] All details from MWS Journals, 103-108. Nb. No journal by Mary (lost) from 13 May 1815 – 21 July 1816.

[2] ‘The impression given by these accounts [Mary Shelley’s intro, PBS’s preface and Thomas Moore] is of a leisurely time-scheme, yet it must in fact have been fairly brief: Byron met Shelley’s party at Sécheron on 27 May, and did not move to the Villa Diodati until 10 June; the journey round Lake Leman began on 22 June, and the novel must have been started between these last two dates’. M. K. Joseph ‘The Composition of Frankenstein’ in Frankenstein ed. J. Paul Hunter (London: Norton, 1996 repr. 2012), 171.

[3] MWS, Journals, 22, 26, 649-50, 684.

Frankenstein at the fondation Martin Bodmer in Geneva, review by Anna Mercer

The Frankenstein exhibition at the Fondation Martin Bodmer in Geneva provides a journey, in which you first encounter the Shelleys’ works, and then the connections within those works to Geneva itself. We are presented with contemporary scenes of Geneva (in order to understand the Swiss town as Mary would have seen it), and the more unchanging forms of the French Alps.

My Guest Contributor series continues with another article by Anna Mercer. Anna as readers of this space will known has studied at the University of Liverpool and the University of Cambridge. She is now in her third year as an AHRC-funded doctoral candidate at the Centre for Eighteenth Century Studies, University of York. Her research focuses on the collaborative literary relationship of Percy and Mary Shelley. She won the runner-up Keats-Shelley Prize in 2015 for her essay on the Shelleys, which was published in the Spring 2016 issue of the Keats-Shelley Review. A new article on this subject is due to appear in the forthcoming issue of the same magazine.

I myself made this visit, twice in fact, and an attest the the extraordinary character of this exhibition. This January I will be introducing an audio-visual component to this space in the form of a series of VLOGs. The inaugural VLOG will focus on the time the Shelley's spent at Diodati and what I believe Diodati stands for. But enough of that, let me turn the podium over to Anna!

In June 2016 I spent five days in Geneva and south east France, travelling in the footsteps of the Shelleys (the details of which – including the Shelleys’ experience, and my own experience, of the Mer de Glace – will be a future blog). On the third day I met Prof. David Spurr from the University of Geneva at the Bodmer Foundation Library and Museum. Spurr had kindly agreed to show us around the current exhibition: Frankenstein: Creation of Darkness, which he curated.

As my partner and I drove across the border from France into Switzerland, and around the beautiful Cologny area of Geneva, we caught a glimpse of Mont Blanc in the distance, a momentous sight; our trip to Chamonix the day before had been so cloudy, rainy and misty that it had seemed as if the mountain was determined to hide from our view. We welcomed the sunshine and we arrived at the Bodmer, which is in a stunning location, and well worth a visit. It opened in 1951, and was initially a research library, but in 2003 an exhibition space was opened, which in itself is an amazing piece of architecture.

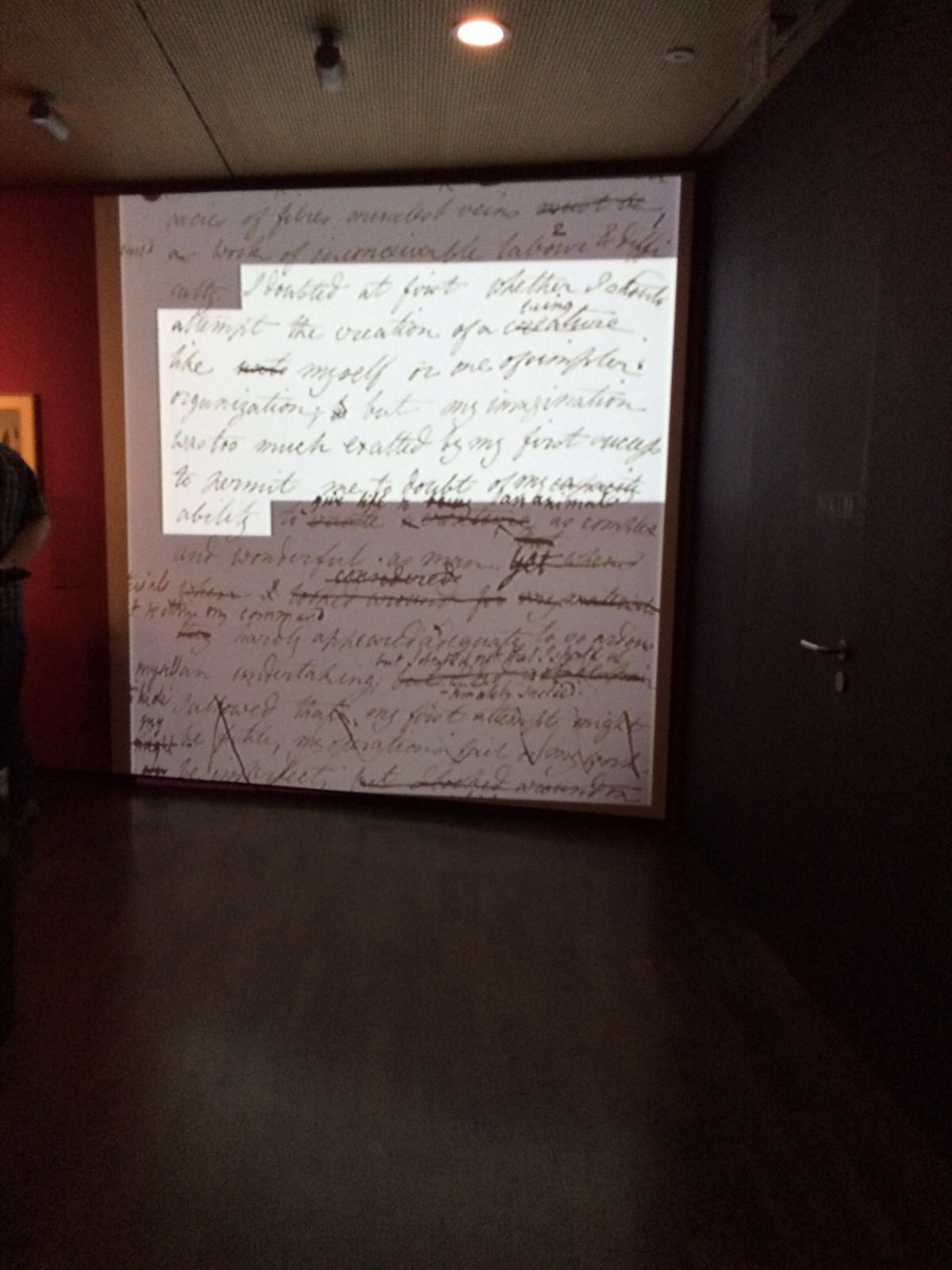

Spurr’s tour of the Frankenstein exhibition took us through the manuscripts, books and pictures on show as a story of the text’s history and conception, and all the many literary and artistic influences on Frankenstein, as well as those things which have been influenced by it. The exhibition has (of course) been set up to celebrate the 200th anniversary of the writing of Mary Shelley’s iconic novel. The blurb tells us that the exhibition considers ‘the origins of Frankenstein, the perspectives it opens and the questions it raises.’

The exhibition provides a journey, in which you firstly encounter the Shelleys’ works, and then the connections within those works to Geneva itself. We are presented with contemporary scenes of Geneva (in order to understand the Swiss town as Mary would have seen it), and the more unchanging forms of the French Alps.

Cologny, view of Geneva from the Villa Diodati by Jean Dubois, late 19th century / Centre d’iconographie genevoise, Bibliothèque de Genève

These images are placed on the wall alongside a large glass cabinet holding the treasure of the exhibition: the Frankenstein draft notebooks. The pages on show include the section that would become Vol II, Chapter II of the 1818 Frankenstein where Mary Shelley quotes Percy Bysshe Shelley’s ‘Mutability’. It was exciting to see the original draft of this page, as I often use the manuscript facsimile version in my research. What is fascinating here is that Mary inserts poetry so seamlessly into her dense prose descriptions of Victor’s solitary Alpine travels and fluctuating moods. Moreover, that poetry is composed by her partner Percy Shelley, who then goes over the draft of the novel and makes occasional suggestions to aid her in her task. Within the Frankenstein notebook (which can be also be viewed online at the Shelley-Godwin Archive), you can see how Percy Shelley glosses Mary’s original language, something which is endlessly fascinating.

We are as clouds that veil the midnight moon;

How restlessly they speed, and gleam, and quiver,

Streaking the darkness radiantly!-yet soon

Night closes round, and they are lost for ever:

Or like forgotten lyres, whose dissonant strings

Give various response to each varying blast,

To whose frail frame no second motion brings

One mood or modulation like the last.

We rest. – A dream has power to poison sleep;

We rise. – One wandering thought pollutes the day;

We feel, conceive or reason, laugh or weep;

Embrace fond woe, or cast our cares away:

It is the same!- For, be it joy or sorrow,

The path of its departure still is free:

Man’s yesterday may ne’er be like his morrow;

Nought may endure but Mutability.

P B Shelley, ‘Mutability’ (1816). Verses 3 and 4 appear in Frankenstein.

Another particular highlight for me was Mary Shelley’s journal – open on the page which shows her first reference to the composition of Frankenstein – ‘write my story’ (24 July 1816). The bicentenary of this journal entry will be celebrated at an upcoming event I am organising at York and the Keats-Shelley House this month. The choice of which pages to display from these hugely important holographs has been executed wonderfully at the Bodmer exhibition. Mary’s journal has no facsimile (although there is a brilliant print edition, edited by Paula R. Feldman and Diana Scott-Kilvert), so to see a volume of it was a powerful reminder that it is a tiny book, heavily worn and containing some of her less decipherable jottings.

The exhibition does not only explore the history of the novel’s author and the scenes that she visited and then used in her text, but also places Frankenstein in a wider literary and socio-political context. As the exhibition explains:

“Mary Shelley’s novel continues to demand attention. The questions it raises remain at the heart of literary and philosophical concerns: the ethics of science, climate change, the technologisation of the human body, the unconscious, human otherness, the plight of the homeless and the dispossessed.”

Some of the exhibits on display are on loan from libraries in the UK, such as the Bodleian and the British Library. Others belong to the Bodmer’s own collection. I was particularly excited to see Mary Shelley’s inscription in the copy of the novel she sent to Lord Byron. This was on sale a while ago at Forbes and eventually went for at least £350,000. She writes: ‘To Lord Byron / from the author’ . Her characteristic modesty is evident here, and to be confronted with this edition reminded me of the complex relationship Mary Shelley actually had with Lord Byron, as she was a major copyist for his works, including The Prison of Chillon and Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage Canto III. Also on show at the exhibition is the letter from Lord Byron to John Murray explaining that Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein (Murray being the publisher who first rejected the work). Frankenstein was published anonymously on January 1, 1818: Byron’s choice to reveal her authorship here is testament to his respect for Mary Shelley as a writer, and his determination to deliver her the credit she deserves.

The signed copy of Mary Shelley. Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus which went on sale for £350,000. Photo: Peter Harrington

Other literary texts from the period are displayed, including Jane Austen’s Emma (which first appeared in 1816), Polidori’s diary (a subjective record of the infamous events at the Villa Diodati in the summer of 1816), and a copy of Fantasmagoriana (the collection which prompted Byron’s decision to announce a ghost-story competition). Other more idiosyncratic items include the weather report from Geneva in the summer of 1816, showing low temperatures of 7-10 degrees: indeed, it was the year without a summer. Considerable attention is also paid to the relics of Frankenstein as a stage production, including the various castings of the creature.

Spurr gave us fantastic anecdote-enforced fragments of the Shelleys’ history and the story of the exhibition, and then took us along to the Villa Diodati (a 5-minute walk), where we were treated to a stroll round the gardens. The house is privately owned, but beautifully cared for (as we were told) in a way that is in keeping with its momentous history.

It is worth noting just how well the literary texts were placed on display at the exhibition in Geneva, a difficult feat for any curator, as old books are not as blatantly striking as other forms of artwork. This many Shelley texts have not been on display together since Shelley’s Ghost at the Bodleian.

Other non-Shelleyan exhibits include a display of the texts the creature initially reads and learns from: Milton’s Paradise Lost, a volume of Plutach’s Lives, and Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther. Editions of Rousseau remind the visitor that Lord Byron and the Shelleys were also literary tourists when they first travelled to Switzerland in May/June 1816. The exhibition does a superb job in asserting the powerful contribution and legacy these authors created by composing their own works right there, in Geneva, taking their inspirations from the scenes around them. Moreover, it emphasises the creative stimulation provided by the social environment of reading and intellectual discussion at the Villa Diodati.

(Unless mentioned otherwise, all photos are the author’s own).

The Frankenstein exhibition as featured in other articles from the web:

This post first appeared on the blog of the Wordsworth Trust on 3 July 2016 and is reproduced with their kind permission. The original post can be found here

The Shelleys and "Mutability" by Anna Mercer

P B Shelley’s ‘Mutability’ can, in this way, promote discussion of the Shelleys’ creative collaboration. What we know of the Shelleys’ history provides evidence for their repeated intellectual interactions, as Mary Shelley’s journal shows an almost daily occurrence of shared reading, copying, writing and discussion. The Shelleys’ shared notebooks (not just the ones containing Frankenstein) also indicate that they would use the same paper to draft, redraft, correct and fair-copy their works.

My Guest Contributor series continues with another article by Anna Mercer. Anna as readers of this space will known has studied at the University of Liverpool and the University of Cambridge. She is now in her third year as an AHRC-funded doctoral candidate at the Centre for Eighteenth Century Studies, University of York. Her research focuses on the collaborative literary relationship of Percy and Mary Shelley. She won the runner-up Keats-Shelley Prize in 2015 for her essay on the Shelleys, which has just been published in the Spring 2016 issue of the Keats-Shelley Review.

Anna has given me permission to reprint an article that was originally published as part of the British Association for Romantic Studies' the ‘On This Day’ blog. Anna discusses P B Shelley’s ‘Mutability’ and the inclusion of this poem in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. You can find the original post here.

I think this is an extremely important addition to the Guest Contributors series because it introduces the concept of collaboration. When I was a student in the 1970s and 80s, the idea that Mary had meaningfully collaborated with Shelley* on anything was unheard of. Indeed, the extent of Shelley's involvement in Frankenstein was poorly understood. The modern era has been, however, exceedingly kind to Mary and rather less so for for Shelley. As I have alluded to elsewhere, undergraduates around the world can be forgiven for being literally unaware of a personage by the name Percy Shelley; Mary is all anyone seems to talk about. While on the one hand this may be seen as an much overdue re-balancing of the scales of history, on the other it might be thought of as over-kill. This is where Anna comes in, guiding us through the complicated waters of one of the most interesting literary partnerships in the English language.

I think that today no one should approach the poetry of Shelley without understanding that these two creative people without question influenced one another. This will be a topic for one of my own blogs in the coming months, and I hope Anna will allow me to publish more of her work in this area in the future. Now, an area where Anna and I might disagree would be on the question of whether this poem offers evidence of philosophical idealism. My belief is that even by 1815, Shelley was such a thorough-going philosophical skeptic (in the tradition of Cicero, Hume and Drummond) that this is doubtful. This is, however, a quibble, and with that thought, let's turn to one of the modern experts on the subject of Shelleyan collaboration, Anna Mercer.

* A note on my choice of names. For most of the past two centuries, it has been common to refer to Mary Shelley as "Mary" and Percy Shelley as "Shelley". More recently many writers, such as Anna, now refer to them both by their given names. For my part, what matters is that fact that this is the manner in which they invariably referred to one an other; and so I stick with the old ways. I hope this will offend no one.

The Shelleys and "Mutability" by Anna Mercer

Percy Bysshe and Mary Shelley, from portraits in the Bodleian Library, Oxford.

We are as clouds that veil the midnight moon;

How restlessly they speed, and gleam, and quiver,

Streaking the darkness radiantly!--yet soon

Night closes round, and they are lost forever:

Or like forgotten lyres, whose dissonant strings

Give various response to each varying blast,

To whose frail frame no second motion brings

One mood or modulation like the last.

We rest.--A dream has power to poison sleep;

We rise.--One wandering thought pollutes the day;

We feel, conceive or reason, laugh or weep;

Embrace fond woe, or cast our cares away:

It is the same!--For, be it joy or sorrow,

The path of its departure still is free:

Man's yesterday may ne'er be like his morrow;

Nought may endure but Mutability.

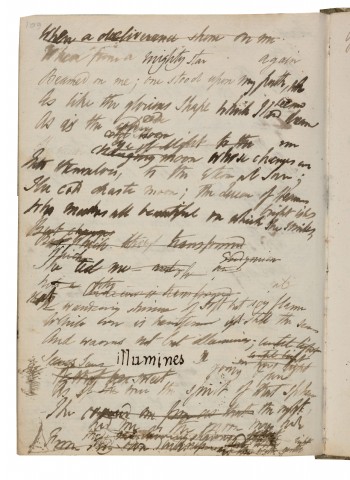

P B Shelley’s ‘Mutability’ is an example of his extraordinary poetic talent; in particular these lines show his ability to weave together philosophical ideas and striking imagery within a short section of verse. In this way the poem is reminiscent of Shelley’s famous sonnets such as ‘Ozymandias’ and ‘England in 1819’. However, ‘Mutability’ was written before these other works, which were composed in 1817 and 1819 respectively. The exact date of composition for ‘Mutability’ is not known: the editors of the Longman edition of The Poems of Shelley assign it to ‘winter 1815-16 mainly on grounds of stylistic maturity’. However, the opening lines ‘suggest a late autumn or winter night, but this could have been equally well a night in 1814’.

The ‘On This Day’ blog series thus far has focused on the bicentenaries of events from 1815: if the most likely dating for ‘Mutability’ places its composition in the winter of 1815, the poem must have lingered in the mind of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, who would include lines from ‘Mutability’ in Chapter II, Vol II of Frankenstein (1818). Mary Shelley did not begin writing this novel (her first full-length work) until the summer of 1816, which she spent with Percy Shelley, Lord Byron, Claire Clairmont and John William Polidori in Geneva.

Joseph Mallord William Turner. Mont Blanc and the Glacier des Bossons from above Chamonix, dawn 1836.

It is interesting that we see Percy Shelley’s maturity emerging in ‘Mutability’, as the editors of the Longman Poems of Shelley establish. This maturity can be understood as Shelley’s fine-tuning of his philosophical expressions into a more coherent idealism. The poem’s almost universal application to any ‘man’ who lives on to the ‘morrow’ may be why Mary Shelley chose to place two stanzas (ll.9-16) in her first novel. They appear just before Victor Frankenstein reencounters his creation for the first time since its ‘birth’. He sets off on a precipitous mountain climb to the glaciers of Mont Blanc – alone – in an attempt to combat his anxiety and melancholy state of mind:

The sight of the awful and majestic in nature had indeed always the effect of solemnizing my mind, and causing me to forget the passing cares of life. I determined to go alone, for I was well acquainted with the path, and the presence of another would destroy the solitary grandeur of the scene.

Victor’s view of the valley, the ‘vast mists’, and the rain pouring from the dark sky, prompt him to lament the sensibility of human nature. As in P B Shelley’s ‘Mutability’, the narrator considers the inconstancy of the mind. This meditation presents a powerful contradiction that inspires both hope and hopelessness by reminding the reader that a potential for change is always present, whether fortunes be good or bad, whether the individual is positively or negatively affected by his/her surroundings. Either way, all might be completely altered over a short space of time as the human mind responds to external influences. Just as Percy Shelley writes ‘Man’s yesterday may ne’er be like his morrow; / Nought may endure but Mutability’, Mary Shelley’s protagonist considers how ‘If our impulses were confined to hunger, thirst, and desire, we might be nearly free; but now we are moved by every wind that blows, and a chance word or scene that that word may convey to us’. Lines 9-16 of Shelley’s poem are inserted in the novel after this sentence. Percy Shelley read and edited the draft of Mary’s Frankenstein, and Charles E. Robinson (editor of the Frankenstein manuscripts) has described the possibility of the Shelleys being ‘at work on the Notebooks at the same time, possibly sitting side by side and using the same pen and ink to draft the novel and at the same time to enter corrections’. The inclusion of the lines from ‘Mutability’ could even have been a joint decision.

Sir Walter Scott’s favourable review of Frankenstein from 1818 (when the novel was published anonymously) assumes this poetical insert to be the same authorial voice as its surrounding prose: ‘The following lines […] mark, we think, that the author possesses the same facility in expressing himself in verse as in prose.’ But instead, the implication is that Mary’s prose seamlessly leads into Percy Shelley’s verse, and illustrates the unity of their diction and their collaborative writing arrangement at this time.

A page from Mary Shelley’s journal (1814) showing both Mary and Percy’s hands. Bodleian Library, Oxford.

Mary Shelley’s journal shows that the Shelleys read S T Coleridge’s poems in 1815. Lines 5-8 of ‘Mutability’ indicate the possibility of a Coleridgean interest based on STC’s conversation poem ‘The Eolian Harp’. As Coleridge describes ‘the long sequacious notes’ which ‘Over delicious surges sink and rise’, Percy Shelley writes: ‘Or like forgotten lyres, whose dissonant strings / Give various response to each varying blast’. The Aeolian Harp or wind-harp (named after Eolus or Aeolus, classical god of the winds) is an image that reoccurs in Romantic poetry and prose. However it is significant that P B Shelley used it in common parlance with Mary, i.e. when writing letters. On 4 November 1814, he writes to her:

I am an harp [sic] responsive to every wind. The scented gale of summer can wake it to sweet melody, but rough cold blasts draw forth discordances & jarring sounds.

P B Shelley’s ‘Mutability’ can, in this way, promote discussion of the Shelleys’ creative collaboration. What we know of the Shelleys’ history provides evidence for their repeated intellectual interactions, as Mary Shelley’s journal shows an almost daily occurrence of shared reading, copying, writing and discussion. The Shelleys’ shared notebooks (not just the ones containing Frankenstein) also indicate that they would use the same paper to draft, redraft, correct and fair-copy their works. Beyond the Frankenstein notebooks, there are even instances of the Shelleys altering and/or influencing each other’s compositions in a reciprocal literary dialogue (something my work as a PhD candidate at the University of York is seeking to identify and explore in depth). If ‘Mutability’ was written in winter 1815 (or even earlier), maybe Mary Shelley looked over it, and kept it in mind in relation to her own creative writing – and therefore the poem found its way into her first novel. These details suggest that the Shelleys’ literary relationship was blossoming in the winter of 1815 (exactly 200 years ago), prior to their most significant collaboration on Frankenstein in 1816-1818.

References:

S. T. Coleridge, The Complete Poems ed. by William Keach (London: Penguin, 1997 repr. 2004) p. 87, 464.

Charles E. Robinson (ed.), ‘Introduction’ in Mary Shelley, The Frankenstein Notebooks Vol I (London: Garland, 1996), p. lxx.

Sir Walter Scott, ‘Remarks on Frankenstein’ in Mary Shelley: Bloom’s Classic Critical Views (New York: Bloom’s Literary Criticism, 2008) p. 93.

Mary Shelley, Frankenstein: A Norton Critical Edition ed. by J. Paul Hunter (London: 1996 repr. 2012) pp. 65-67.

Percy Bysshe Shelley, ‘Mutability’ in The Poems of Shelley Vol I ed. by Geoffrey Matthews and Kelvin Everest (London: Longman, 1989) pp. 456-7.

Teaching Percy Bysshe Shelley, by Anna Mercer

As an undergraduate at the University of Liverpool, I was given A Defence of Poetry to read for a seminar that – and this sounds hyperbolic, but is in reality no exaggeration – I now realise in retrospect changed my life.

My Guest Contributor series continues with an article by Anna Mercer. Anna has studied at the University of Liverpool and the University of Cambridge. She is now in her third year as an AHRC-funded doctoral candidate at the Centre for Eighteenth Century Studies, University of York. Her research focuses on the collaborative literary relationship of Percy and Mary Shelley. She won the runner-up Keats-Shelley Prize in 2015 for her essay on the Shelleys, which has just been published in the Spring 2016 issue of the Keats-Shelley Review.

Anna has given me permission to reprint an article that was originally published as part of the ‘Teaching Romanticism’ series on Romantic Textualities. You can find Anna's own website here. Anna writes extensively on the Shelleys and her articles appear regularly on the web, including this gem from the blog at The Wordsworth Trust: "In the Footsteps of the Shelleys" Here she recounts a visit she made to Lerici, where Shelley died almost 200 years ago. I wasinterested in that post because my father had made a similar pilgrimage decades ago. I have an upcoming blog planned that will cover the peculiar circumstances of my father's and my own divergent interests in Shelley.

However, I am particularly interested in Anna's post here because it complements my own interest in how Shelley is taught. I believe Shelley (and Romantic studies) in general will need to undergo a virtual revolution if we are to start seeing him taught properly. You can find some of my own thoughts on this (and compare them to Anna's) in the Shelley Section in my article "Shelley in the 21st Century"

Here is her article:

I will be teaching undergraduates for the first time in Spring 2015. One anxiety I have is that new readers may come to the works of the ‘big’ Romantic poets with presumptions about their iconic status and therefore their work. Shelley has had perhaps one of the most unsettled critical histories of any Romantic figure: Matthew Arnold infamously branded him an ‘ineffectual angel’ in 1881, and although this misrepresentation has gradually and persistently been disproved in scholarship, the Romantics as a group of aristocratic, white, male, imaginative authors (of course, they all are not always these things, but Shelley is), writing 200 years ago, can sorely influence a new reader’s judgement of them. Surely it is important to establish that Shelley was actually philosophical, radical and political, as well as capable of writing beautiful verse effusions.

One of the critical minds responsible for establishing Shelley’s power was Kenneth Neill Cameron, who in 1942 wrote that ‘the key to the understanding of the poetry, in fact, is to be found in the prose’. More recent Shelley scholarship presents these works side by side, such as in the Norton critical editions. As an undergraduate at the University of Liverpool, I was given A Defence of Poetry to read for a seminar that – and this sounds hyperbolic, but is in reality no exaggeration – I now realise in retrospect changed my life. All of those famous phrases, ‘A Poet is a nightingale who sits in darkness, and sings to cheer its own solitude with sweet sounds; his auditors are as men entranced by the melody of an unseen musician, who feel that they are moved and softened, yet know not whence or why’, ‘for the mind in creation is as a fading coal which some invisible influence, like an inconstant wind, awakens to transitory brightness’, and of course, ‘Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the World’, struck me. I don’t believe I had any predetermined disposition towards Shelley and his writing; in fact, I knew nothing of Shelley before I picked up Duncan Wu’s excellent anthology for the first time as a nineteen year old, and I had never studied the long eighteenth century before.

Connecting prose with poetry in Romanticism is a critical understanding that is long established, obviously originating from the Romantics themselves. I do not know if the poems are taught in universities in isolation, but this should not be the case: and especially not with Shelley. Comparably, we know that one way of getting readers interested in the style of Lyrical Ballads is to read Wordsworth’s preface, or that to understand aspects of Coleridge’s poetics is to read the Biographia Literaria. Directing students towards Shelley’s prose gives them a wealth of understanding unparalleled by reading the verse alone, even with the abundance of criticism available.

As a research student, whose thesis focuses on both Percy Bysshe and Mary Shelley, I have contemplated my aspiration to present these two inextricably linked authors in a way that is inspiring, equal, and above all relevant to (both of) their turbulent critical histories. It is appropriate here (and especially as I believe as both Shelleys should be read very closely together) to say that Frankenstein by Mary Shelley can be interpreted in such a vast variety of ways that the text occasionally eclipses its author’s voice: the notorious night of ghost story telling in Geneva in 1816 dominates perceptions of Mary Shelley’s creativity as a writer.

The relevant problem here is how then to introduce students to P. B. Shelley, whose reputation precedes him, both as a ‘Romantic’ poet, and as an individual present during that night in Geneva. The biographies of P. B. Shelley, and Mary Shelley, often overshadow the reason why they are established literary figures in the first place.

I do not pretend that the Shelleys’ turbulent lives did not in fact attract my own attention as a new literature student some years ago. Adolescent genius, forbidden love, undeniable intellect, and the combination of scholarship and drama contribute to the Shelleys’ intrigue. Yet Mary Shelley’s insight into her husband’s poetry is necessarily literary, and reminds us why we are interested in him at all: because of his poetic genius. In her 1839 Preface to P. B. Shelley’s Poetical Works, she explains how ‘his poems may be divided into two classes’:

"the purely imaginative, and those which sprung from the emotions of his heart. […] The second class is, of course, the more popular, as appealing at once to emotions common to us all."

This is the complexity of the poetry of P. B. Shelley, and what has to be conveyed to new readers. He can, in some verses, portray the beautiful in the everyday misery:

When the lamp is shattered

The light in the dust lies dead—

When the cloud is scattered

The rainbow’s glory is shed.

When the lute is broken,

Sweet tones are remembered not;

When the lips have spoken,

Loved accents are soon forgot. (‘When the Lamp is Shattered’, 1-8)

I remember hearing this poem for the first time in a lecture by Prof. Kelvin Everest; he explained its stunning intricacy as both relatable and idealistic. The poem on first reading has that Romantic simplicity from which the complexity must be extracted. It is therefore at once accessible and challenging. Shelley also has many poems, which are commonly misread assimply personal but in actuality are far more complicated than that.