What Shelley Means to Me

Allow me to introduce you to Oliver. Oliver popped up one day on my twitter feed. Oliver’s pronouns are they/their and they are a high school student living in Michigan. Oliver has an incredible passion for poetry and Shelley in particular. Oliver started asking for book recommendations - and they devoured them. They started doing research and bringing new findings and perspectives to our twitter feeds. Oliver started engaging with a large cross-section of the online Shelley community - ranging from amateur fans to some of the most respected academic authorities in the world!

Introduction to Oliver

Years ago when my interest in the revolutionary writer Percy Bysshe Shelley was revived, my first instinct was to create a community. I wanted to share my passion for Shelley with a wide audience. And so this site was born.

I devoted a lot of time and money to building it. But I very quickly discovered that the dictum "build it and they will come" did not operate in cyberspace! And so I needed to develop strategies to engage a wider non-academic audience. To do that I created companion amplification outlets on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. The effect was catalytic, and my audience grew rapidly around the world. For example, one of the largest audiences I have on Facebook is in Italy.

But I wanted more! And so I hired technical experts to help me with the search engine optimization of the site. It worked. Almost immediately The Real Percy Bysshe Shelley became more visible and easy to find in the audience grew again.

One audience, however, proved elusive: the younger generation. Where were they? How was I to find them? Did I have to create a TikTok site!? Perhaps I do. In any event, one day I got lucky.

Allow me to introduce you to Oliver. Oliver (they/them) is a high school student living in Midwestern United States. They popped up one day on my Twitter feed. Oliver was inquisitive and eager; asking all kinds of questions and for book recommendations among other things. They seemed particularly interested in Shelley’s more radical, political poetry and essays which was very gratifying to me personally. WhileI know they were nervous at first, that didn't prevent them from rapidly integrating into the community and interacting with an incredibly wide range of Shelleyans; including some of the most distinguished academic scholars in the world! We started to joust with Shelley-pals like Bysshe Coffey on a wide range of subjects.

It's suddenly occurred to me, that I should be asking a young person such as Oliver to write for this site. And so I did. And Oliver agreed! And am I ever glad I did and they did! What Oliver produced was heartfelt, poignant and uplifting. If I never do anything again with this site, this will be enough and I will be happy. Having fired a young person’s mind with a passion for Shelley is more than I could've hoped for. There is a forest in every acorn.

Thank you, Oliver, for you fearless, inquiring mind, thank you for taking a chance; and thank you for writing this beautiful essay. Onward!!

What Percy Bysshe Shelley Means to Me, a Young Person From Minority and Marginalized Groups

by Oliver

Shelley to me is a person who could see hope and light in the darkness that surrounds people. To me he feels like someone who was a protector. And not just a protector of his loved ones alone, but also of people who have faced harsh words from others who in order to feel better about themselves bring others down.

That man was not a poet who just wrote about politics and nature but a writer and poet for the people who can’t get up in the morning because depression and anxiety are pushing them down. He is a guardian to lost children and teenagers who have to face the fact that their parents are struggling and not listening to their needs. Shelley speaks for those who aren’t listened to by authority figures.

To me, Percy is the poet of the different and silenced people of oppressed groups. He spoke in words that may be hard to understand to some but which nonetheless get the meaning across. He writes for the lost and hurt - people who have suffered because of their oppressors. His poetry is something that should be cherished by the people for whom it was written. And it also deserves attention from the wider general public.

I look at my small collection of books I have about him and by him. They sit on my shelf and it feels like he’s always been there for me. I read his poems and seek to learn his messages. I believe that he’s been here since I first experienced loss in my life. He feels like a spirit that watches over us and swoops into our minds whenever he is needed. It seems like he’s always there when it feels like I can’t do anything right and yet I’m trying so hard to do things the right way. I learned from him that I don’t want to do everything that adults and authority figures say I must. He supports my belief that I’m my own person and don’t have to follow their way of thinking just because I’m a teenager. He supports my belief that I don’t have to conform to their ways of thinking; because I’m not like them at all. I am not a student of my school, I feel like I am a student of Shelley and my mentors in these studies.

This isn’t everything I want to say about Percy Shelley and definitely is not the last of how I’ll write and speak of him. Hopefully we will see no end to people sharing his words with others and speaking them in times when it seems right and. His legacy will be kept alive in this way!

Oliver is a high school student living in Michigan. Their favourite poem by Shelley is The Mask of Anarchy and right now they are reading Richard Holmes biography of PBS: “Shelley, The Pursuit.” However, Oliver’s favourite biography is the one by James Bieri. When asked what question they might ask Percy were they to meet him, Oliver suggested this: “How do you think people will see your life once you’re gone.” I would love to get an answer to that myself! Oliver would one day like to be a writer and a member of the Keats Shelley Association of America. You can find Oliver on Twitter here.

“Fear not for the future - Percy Shelley”

Eleanor Marx Speaks!!! "Shelley's Socialism"

This is a Marxist evaluation of the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley by Eleanor Marx and Edward Aveling. It was delivered as a speech to the Shelley Society in April of 1888. This is the only complete and authoritative version of the speech that is available on line. It is almost impossible to find in a printed format.

Editor’s Introductory Note

According to Marx’s biographer Yvonne Kapp, Shelley’s Socialism was first published by To-day: The Journal of Scientific Socialism in 1888 (Yvonne Kapp, Eleanor Marx, p. 450). It also appeared as a pamphlet in an edition of only twenty-five copies published (presumably by the Shelley Society) for private circulation under the title Shelley and Socialism. In 1947, Leslie Preger (a young Manchester socialist who had fought in the Spanish Civil War) arranged to have it published, with an introduction by the Labour politician Frank Allaun through CWS Printing Work. The Preger edition can be found online through used book services such as AbeBooks. The version published by Preger and that which appeared in To-Day are somewhat different. The version which appears in To-Day appears to have been lightly edited and omits several selections from Shelley’s poetry that appear in the Preger edition. My assumption is that Preger reproduced the pamphlet version released by the Shelley Society. The version I have made available (see link below) is based on Preger and thus is the only complete and “authoritative” version of the speech (as delivered) available on line.

In their speech, Marx and Aveling refer to a second part which they intended to deliver upon some future occasion. Either the second installment has been either lost or perhaps it was never delivered. However, Kapp tantalizingly points out that Engels in fact translated the second part into German for publication in Germany by Die Neue Zeit (Kapp p. 450). No trace of it appears to exist - a loss for us all given the intended subject matter discussed in the speech.

Frank Allaun, author of the preface to the Preger edition, offered this encapsulation of the speech: “A Marxist evaluation of the poetry of Percy Bysshe Shelley.” He concludes his preface with this sage assessment:

“Shelley, who died when his sailing boat sinking a storm in 1822, lived when the Industrial Revolution was only beginning. The owning class had not yet "dug their own graves" by driving the handloom weavers and other domestic workers from their kitchens and plots of land into the "dark satanic mills" alongside thousands of other operatives. Conditions were not ripe for the modern trade union and socialist movement. Had they been so Shelley would have been their man.”

Of the authors, George Bernard Shaw said "he (Aveling) was quite a pleasant fellow who would've gone to the stake for socialism or atheism, but with absolutely no conscience in his private life. He said seduced every woman he met and borrowed from every man. Eleanor committed suicide. Eleanor's tragedy made him infamous in Germany". Shaw added, "While Shelley needs no preface that agreeable rascal Aveling does not deserve one.”

Eleanor Marx was an extraordinary person who deserves far more attention from our modern society. According to Harrison Fluss and Sam Miller writing in Jacobin, Marx was

born on January 16, 1855, Eleanor Marx was Karl and Jenny Marx’s youngest daughter. She would become the forerunner of socialist feminism and one of the most prominent political leaders and union organizers in Britain. Eleanor pursued her activism fearlessly, captivated crowds with her speeches, stayed loyal to comrades and family, and grew into a brilliant political theorist. Not only that, she was a fierce advocate for children, a famous translator of European literature, a lifelong student of Shakespeare and a passionate actress.

To which we can add that she was also devotee of and influenced by Percy Shelley. Both Eleanor and Aveling were immersed in culture - much like Karl Marx himself. This was not Aveling’s first foray into the subject matter. In 1879 he had given a speech about Shelley to the Secular Society - described by Annie Besant as a “simple, loving, and personal account of the life and poetry of the hero of the free thinkers..” (Kapp, p. 451) This assessment, by the way, is yet another indication of the high regard accorded to Shelley by the socialist community. According to her Wikipedia entry, Besant was was a

“British socialist, theosophist, women's rights activist, writer, orator, educationist, and philanthropist. Regarded as a champion of human freedom, she was an ardent supporter of both Irish and Indian self-rule. She was a prolific author with over three hundred books and pamphlets to her credit.”

That she considered Shelley to be the “hero of freethinkers” is telling and a further reminder of the influence Shelley had on 19th century socialists. Kapp perceptively points out that:

“There can be no doubt that this lecture, though delivered by Aveling, was it to collaboration between two people who had long and devotedly studied the poet with equal enthusiasm, Aveling primarily as an atheist, Eleanor as a revolutionary…”

You can read a wonderful encapsulation of Eleanor Marx and her legacy in the Jacobion, here. And you can buy Kapp’s biography of Eleanor Marx here, though I strongly suggest you instead order it through your local bookseller.

Read my analysis of this speech here.

- Graham Henderson

"We claim him as a socialist" - Eleanor Marx to the Shelley Society, April 1888

Shelley’s Socialism

by Eleanor Marx and Edward Aveling

Introduction

This paper is, in the first place, an attempt at the treatment of an important subject on the plan that seems to its writers the one most likely to lead to results at once accurate and fruitful. That plan is based upon the co-operation of a man and a woman, whose sympathies are kindred, but whose points of view and methods of looking at facts are as different as are the positions of the two sexes to-day, even in the most favourable conditions, under the compulsion of our artificial and unhealthy society. That which one of us is about to read to you has been talked over, planned, followed in truth written by both of us; and although I am the reader, it must be understood that I am reading the work of my wife as well as, nay more than, of myself.

Only a few of the students of Shelley can lay claim to that encyclopaedic knowledge of all relating to him that is the happy gift of someone or to members of your society, who have fortunately a method equally happy of making all of us cool partners with them in their excellent possession. But many of the rank and file in this army of posey may have a special knowledge of the special subjects considered by the poet-leader. They may know by rule–of–some, perhaps, what he divines by intuition. And just as in the study of browning, help is given when the painter, the musician, or the man of science touches upon Browning’s poetry from the point of view of the specialist, we have thought there may be some interest in a study of Shelly and his writings by those who hold economic and political ideas that are in the main identical with his.

The question to be considered is not whether Socialism is right or wrong, but whether Shelley was or was not a socialist. Whilst at other times and in other places we are perfectly willing to discuss the arguments for or against socialism, at this time and in this place, we can only discuss the position of Shelly in regard to this phase of historical development. It may not be unfair to contend, that if it can be shown that Shelley was a socialist, a prima facia case at least, is in the judgment of every Shelley lover, is made out in favour of Socialism.

That the question at issue may be clearly understood, let us state in the briefest possible way what socialism means to some of us:

(1) That there are inequality and misery in the world;

(2) that this social inequality, this misery of the many and this happiness of the few are the necessary outcome of our social conditions;

(3) that the essence of these social conditions is that the mass of the people, the working class, produce and distribute all commodities, while the minority of the people, the middle and upper classes, possess these commodities;

(4) that this initial tyranny of the possessing class over the producing class is based on the present wage-system, and now maintains all other forms of oppression, such as that of monarchy, or clerical rule, or police despotism;

(5) that this tyranny of the few over the many is only possible because the few have obtained possession of the land, the raw materials, the machinery, the banks, the railways - in a word, of all the means of production and distribution of commodities; and have, as a class, obtained possession of these by no superior virtue, effort or self-denial, but by either force or fraud; and lastly

(6) that the approaching change in “civilised” society will be a revolution, or in the words of Shelley “the system of human society as it exists at present must be overthrown from the foundations.” [a] (Letter to Leigh Hunt. 1May 1820.) The two classes at present existing will be replaced be a single class consisting of the whole of the healthy and sane members of the community, possessing all the means of production and distribution in common, and working in common for the production and distribution of commodities.

Again let us say that we are not now concerned with the accuracy or inaccuracy of these principles. But we are concerned with the question whether they were or were not held by Shelley. If he enunciated views such as these, or even approximating to these, it is clear that we must admit that Shelley was a teacher as well as a poet. The large and interesting question whether a poet has or has not a right to be didactic as well as merely descriptive, analytical, musical, cannot be entered upon now. In passing we may note that poets have a habit of doing things whether they have the right or not. If the gentleman who read some months back, the exceedingly "tedious – brief" paper on a poem of some magnitude, Laon and Cythna, will allow us we should contend that while there is no reason that a poet should of necessity be didactic, there is equally no reason why of necessity he should not be a teacher of the intellect and moral nature as well as of the sense and imagination and although, as has been said, we do not propose to discuss this question tonight, much of our work will serve, as we believe, to strengthen the general position here taken into controvert the extraordinary statement of a speaker at the April meeting and printed in the Notebook of this society that Shelley's "ethics were rotten".

For the purpose of our study the following plan is suggested [for today]:

(1) A note or two on Shelley himself and his own personality, as bearing on his relations to Socialism;

(2) On those, who, in this connection had most influence upon his thinking;

(3) His attacks on tyranny, and his singing for liberty, in the abstract;

(4) His attacks on tyranny in the concrete;

(5) His clear perception of the class struggle; and

(6) His insight into the real meaning of such words as “freedom,'’ “justice,” “crime,” “labour,” and “property”.

We cannot hope today to deal with more than the above. If opportunity offers we shall consider upon some future occasion the following four topics.

(7) His practical, his exceedingly practical nature in respect to the remedies for the ills of society;

(8) His comprehension of the fact that a reconstruction of society is inevitable, is imminent;

(9) His pictures of the future, “delusions that were no delusions,” as he says; and lastly

(10) A reference to the chief works in which his socialistic ideas found expression.

Shelley’s own Personality

He was the child of the French Revolution. “The wild-eyed women” thronging round the path of Cythna as she went through the great city [b] were from the streets of Paris, and he, more than any other of his time, knew the real strength and beauty of this wild mother of his and ours. With his singular poetical and historical insight he saw the real significance of the holy struggle. Another singer of that melodious time, Byron, was also a child of the same Revolution. But his intellectual fore-runners were Voltaire and his school, and the Rousseau of the Nouvelle Héloise, whilst those of Shelley were [François-Noël] Baboeuf and the Rousseau of the Contrat Social. It is a wise child that knows his own father. As Marx, who understood the poets as well as he understood the philosophers and economists, was wont to say: “The real difference between Byron and Shelley is this: those who understand them and love them rejoice that Byron died at thirty-six, because if he had lived he would have become a reactionary bourgeois; they grieve that Shelley died at twenty-nine, because he was essentially a revolutionist, and he would always have been one of the advanced guard of socialism.”

The outbreak of the Revolution was only three years in advance of Shelley’s birth. Throughout Europe in the earlier part of this century reaction was in full swing. In England there were trials for blasphemy, trials for treason, suspension of the Habeas Corpus Act, misery everywhere. Shelley saw — not as Professor Dowden alternately has it, “thought he saw” — in the French Revolution an incident of the movement towards a reconstruction of society. He flung himself into politics, and yet he never ceased singing.

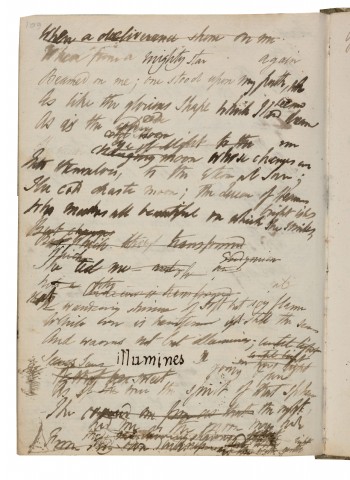

Every poem of Shelley’s is stained with his intense individuality. Perhaps for our purpose the Lines written on the Euganean Hills, the Lionel of Rosalind and Helen, and Prince Athanase afford the best exemplars. But let us also keep in remembrance Mary Shelley’s testimony to the especial value of Peter Bell the Third, in respect to the social and religious views of her husband.

“No poem contains more of Shelley’s peculiar views with regard to the errors into which many of the wisest have fallen, and of the pernicious effects of certain opinions on society ... Though, like the burlesque drama of Swellfoot, it must be looked on as a plaything, it has ... so much of himself in it that it cannot fail to interest greatly, and by right belongs to the world for whose instruction and benefit it was written.” [c]

And now having quoted her we may quote himself upon himself. Whether wholly unconsciously, or with the modest self-consciousness of genius he has written, lines and lines that are word-portraits of himself. Of these only one or two familiar instances can be taken.

He was one of:

“The sacred few who could not tame

Their spirits to the conquerors.”

- Triumph of Life [d]

“And then I clasped my hands and looked around —

But none was near to mock my streaming eyes,

Which poured their warm drops on the sunny ground —

So without shame, I spake: — “I will be wise,

And just, and free, and mild, if in me lies

Such power, for I grow weary to behold

The selfish and the strong still tyrannise

Without reproach or check.” I then controlled

My tears, my heart grew calm, and I was meek and bold.

“And from that hour did I with earnest thought

Heap knowledge from forbidden mines of lore,

Yet nothing that my tyrants knew or taught

I cared to learn, but from that secret store

Wrought linked armour for myself, before

It might walk forth to war among mankind;

Thus power and hope were strengthened more and more

Within me, till there came upon my mind

A sense of loneliness, a thirst with which I pined.”

- Laon and Cytha [e]

He was one of:

“Those who have struggled, and with resolute will

Vanquished earth’s pride and meanness, burst the chains,

The icy chains of custom, and have shone

The day-stars of their age.”

- Queen Mab. [f]

The dedication of The Cenci to Leigh Hunt may be taken as if Shelley was communing with his own heart:

“One more gentle, honourable, innocent and brave; one of more exalted toleration for all who do and think evil, and yet himself more free from evil; one who knows better how to receive and how to confer a benefit though he must ever confer far more than he can receive; one of simpler, and, in the highest sense of the word, of purer life and manners I never knew.”

- Dedication of The Cenci [g]For nought of ill his heart could understand,

But pity and wild sorrow for the same;-

Not his the thirst for glory or command,

….

For none than he a purer heart could have,

Or that loved good more for itself alone;

Of nought in heaven or earth was he the slave.

….

Yet even in youth did he not e'er abuse

The strength of wealth or thought, to consecrate

Those false opinions which the harsh rich use

To blind the world they famish for their pride;

Nor did he hold from any man his dues,

But, like a steward in honest dealings tried,

With those who toiled and wept, the poor and wise,

His riches and his cares he did divide.

Fearless he was, and scorning all disguise,

What he dared do or think, though men might start,

He spoke with mild yet unaverted eyes;- Prince Athanese

Pure-minded, earnest-souled, didactic poet, philosopher, prophet, then he is. But add to this, if you will rightly estimate the immense significance of his advocacy of any political creed, the fact already noted of his extraordinary political insight; and add also, if you will rightly estimate the value of his adherence to any scientific truth, the fact that he had a certain conception of evolution long before it had been enunciated in clear language by Darwin, or had even entered seriously into the region of scientific possibilities. Of his acuteness as historical observer, one general instance has already been given in connection with the French Revolution. Yet another less obvious but even more astounding example is furnished by his poems on Napoleon. Shelley was the first, was indeed the only man of his time to see through Napoleon. The man whom every one in Europe at that period took for a hero or a monster, Shelley recognised as a mean man, a slight man, greedy for gold, as well as for the littleness of empire. His instinct divined a “Napoleon the Little” in “Napoleon the Great”. That which [Jules] Michelet felt was true, that which it was left for [Pierre] Lanfrey to prove as a historical fact, the conception of Napoleon that is as different from the ordinary one, as an ordinary person is from Shelley, this “dreamer” had.

In 1816 we find him writing:

“I hated thee, fallen tyrant! I did groan

To think that a most unambitious slave,

Like thou, shouldst dance and revel on the grave

Of Liberty.” [h]

And in 1821, the year of Napoleon’s death.

“Napoleon’s fierce spirit rolled,

In terror, and blood, and gold,

A torrent of ruin to death from his birth” [i]

By instinct, intuition, whatever we are to call that fine faculty that feels truths before they are put into definite language, Shelley was an Evolutionist. He translated into his own pantheistic language the doctrine of the eternity of matter and the eternity of motion, of the infinite transformation of the different forms of matter into each other, of different forms of motion into each other, without any creation or destruction of either matter or motion. But that he held these scientific truths as part of his creed, there can be no doubt. You have the doctrine, certainly in a pantheistic form, but certainly there, in the letter to Miss Hitchener:

“As the soul which now animates this frame was once the vivifying principle of the lowest link in the chain of existence, so is it ultimately destined to attain the highest.”

- Letters VI., p.12 [k]

In Queen Mab:

“Spirit of Nature! here!

In this interminable wilderness

Of worlds, at whose immensity

Even soaring fancy staggers,

Here is thy fitting temple.

Yet not the lightest leaf

That quivers to the passing breeze

Is less instinct with thee

Yet not the meanest worm

That lurks in graves and fattens on the dead

Less shares thy eternal breath “[l]. (Book 1, 264-274)How wonderful! that even

The passions, prejudices, interests,

That sway the meanest being--the weak touch

That moves the finest nerve

And in one human brain

Causes the faintest thought, becomes a link

In the great chain of Nature! (Book 2, 102-108)'How strange is human pride!

I tell thee that those living things,

To whom the fragile blade of grass

That springeth in the morn

And perisheth ere noon,

Is an unbounded world;

I tell thee that those viewless beings,

Whose mansion is the smallest particle

Of the impassive atmosphere,

Think, feel and live like man;

That their affections and antipathies,

Like his, produce the laws

Ruling their moral state;

And the minutest throb

That through their frame diffuses

The slightest, faintest motion,

Is fixed and indispensable

As the majestic laws

That rule yon rolling orbs.' (Book 2, 225-243)

Of the two great principles affecting the development of the individual and of the race, those of heredity and adaptation, he had a clear perception, although they as yet were neither accurately defined nor even named. He understood that men and peoples were the result of their ancestry and of their environment. Two prose fragments in illustration of this. One is:

“It is less the character of the individual than the situation in which he is placed which determines him to be honest or dishonest.”

- Letter to Hunt. [m]

The other is:

“But there must be a resemblance which does not depend upon their own will, between all the writers of any particular age. They cannot escape from subjection to a common influence which arises out of an infinite combination of circumstances belonging to the times in which they live, though each is in a degree the author of the very influence by which his being is thus pervaded. Thus, the tragic poets of the age of Pericles; the Italian revivers of learning; those mighty intellects of our own country that succeeded the Reformation, the translators of the Bible, Shakespeare, Spenser, the dramatists of the reign of Elizabeth, and Lord Bacon, the colder spirits of the interval that succeeded; all resemble each other and differ from every other in their several classes. In this view of things Ford can no more be called the imitator of Shakespeare, than Shakespeare the imitator of Ford. There were perhaps few other joints of resemblance between these two men, than that which the universal and inevitable influence of their age produced. And this is an influence which neither the meanest scribbler, nor the sublimest genius of any era can escape, and which I have not attempted to escape.” (Preface to Laon and Cythna) F. I. p.57-58).

This extraordinary power of seeing things clearly and of seeing them in their right relations one to another, shown not alone in the artistic side of his nature, but in the scientific, the historical, the social, is a comfort and strength to us that hold in the main the beliefs, made more sacred to us in that they were his, and must give every lover of Shelley pause when he finds himself parting from the Master on any fundamental question of economics, of faith, of human life.

2. The People Most Immediately Influencing Him

We are always speaking of Shelley to-night in relation to his political and social thinking.

A word again upon Byron here. In Byron we have the vague, generous and genuine aspirations in the abstract, which found their final expression in the bourgeois-democratic movement of 1848. In Shelley, there was more than the vague striving after freedom in the abstract, and therefore his ideas are finding expression in the social-democratic movement of our own day. Thus Shelley was on the side of the bourgeoisie when struggling for freedom, but ranged against them when in their turn they became the oppressors of the working-class. He saw more clearly than Byron, who seems scarcely to have seen it at all, that the epic of the nineteenth century was to be the contest between the possessing and the producing classes. And it is just this that removes him from the category of Utopian socialists, and makes him so far as it was possible in his time, a socialist of modern days.

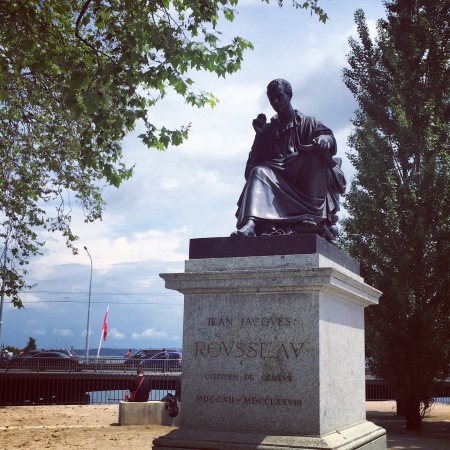

We have already referred to the influence of Baboeuf, (probably indirect), and of Rousseau. To these must of course be added the French philosophes, the Encyclopaedists, especially [Paul-Henri Dietric] Baron d’Holbach, or more accurately his ghost [Denis] Diderot — Diderot [who was] the intellectual ghost of everybody of his time.

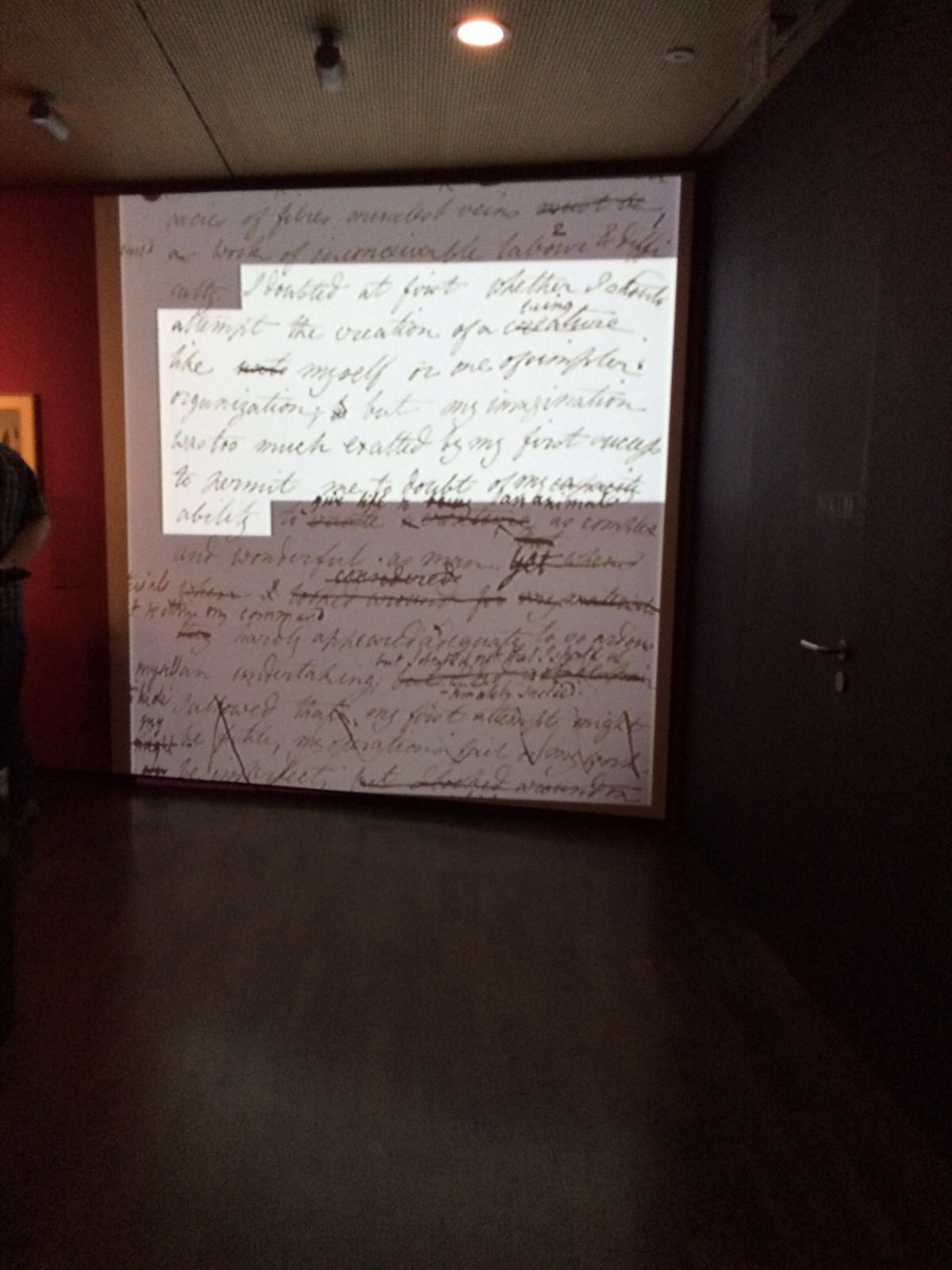

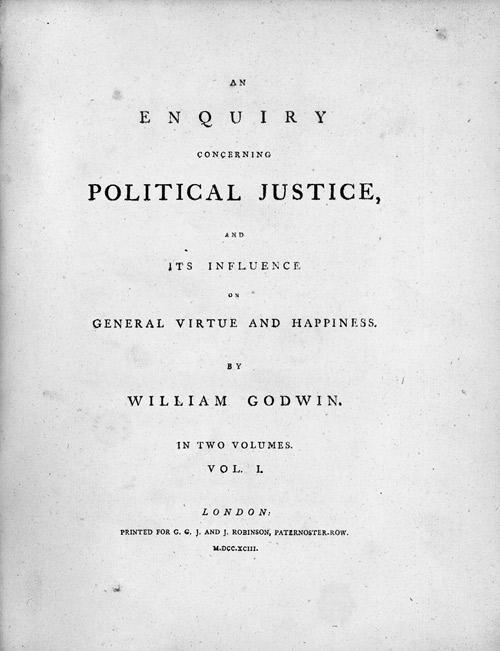

Into any inquiry concerning the writer, that influenced Shelley’s politics and sociology the name of [William] Godwin must necessarily enter prominently. Bowden’s Life, has made us all so thoroughly acquainted with the ill side of Godwin that just now there may be a not unnatural tendency to forget the best of him. But whatever his colossal and pretentious meannesses and other like faults may have been, we have to remember that he wrote Political Justice, a work in itself of extraordinary power, and of special significance to us as the one that did more than any other to fashion Shelley’s thinking. Much has been made, scarcely too much can be made, of the influence of Godwin’s writings on Shelley. But not enough has been made of the influence upon him of the two Marys: Mary Wollstonecraft and Mary Shelley. It was one of Shelley’s “delusions that are not delusions” that man and woman should be equal and united; and in his own life and that of his wife he not only saw this realised, but saw the possibility of that realisation in lives less keen and strong than theirs. All through his work this oneness with his wife shines out, and most notably in the dedication to that most didactic of poems, Laon and Cythna. Laon and Cythna are equal and united powers, brother and sister, husband and wife, friend and friend, man and woman. In the dedication to the history of their suffering, their work, their struggle, their triumph and their love, Mary is “his own heart’s home, his dear friend beautiful and calm and free.”

“And what art thou? I know, but dare not speak:

Time may interpret to his silent years,

Yet in the paleness of thy thoughful cheek,

And in the light thine ample forehead wears,

And in thy sweetest smiles and in thy tears,

And in thy gentle speech, a prophecy

Is whispered, to subdue my fondest fears;

And thro’ thine eyes, even in thy soul I see,

A camp of vestal fire burning internally.”

And in the next stanza to the one just quoted that other Mary is besung.

“One then left this earth

Whose life was like a setting planet mild,

Which clothed thee in the radiance undefiled,

Of its departing glory, still her fame

Shines on thee thro’ the tempests dark and wild,

Which shake these latter days.”

In a word, the world in general has treated the relative influences of Godwin on the one hand and of the two women on the other, pretty much as might have been expected with men for historians.

Probably the fact that he saw so much through the eyes of these two women quickened Shelley’s perception of women’s real position in society, and of the real cause of that position. This, which he only felt in the Harriet days, he would have understood fully of himself sooner or later. That this understanding came sooner, is in large measure due to the two Marys. One of them at least before him had seen in part that women’s social condition is a question of economics, not of religion or of sentiment. The woman is to the man as the producing class is to the possessing. Her “inferiority,” in its actuality and in its assumed existence, is the outcome of the holding of economic power by man to her exclusion. And this Shelley understood not only in its application to the most unfortunate of women, but in its application to every woman. Truly in Queen Mab he writes:

'All things are sold: the very light of heaven

Is venal; earth's unsparing gifts of love,

.....

Are bought and sold as in a public mart

Of undisguising Selfishness, that sets

On each its price, the stamp-mark of her reign.

Even love is sold; the solace of all woe

Is turned to deadliest agony, old age

Shivers in selfish beauty's loathing arms, (Book V, 178-179 and 186-191)

But note how in the Laon and Cythna it is (F. I. 108, xxi) “woman, [i.e. woman in general] outraged and polluted long.” Now truly he understands the position of woman, and how thoroughly he recognizes that in her degradation man is degraded, and that in dealing out justice to her man will be himself set free, the well-known Laon and Cythna passage will serve to illustrate.

“Can man be free if woman be a slave?

Chain one who lives, and breathes this boundless air

To the corruption of a closed grave!

Can they whose mates are beasts, condemned to bear

Scorn heavier far than toil or anguish, dare

To trample their oppressors? in their home

Among their babes, thou knowest a curse would wear

The shape of woman — hoary crime would come

Behind, and Fraud rebuild religion’s tottering dome.” [n]

It is interesting to compare this and kindred fiery outbursts of practical teaching in Shelley with the uncertain sound and bated breath of the washed out, emasculated, effeminated Shelley, Tennyson, Tennyson. The breath is bated in the latter case because it is that of a respectable gentleman, and the sound is uncertain, as we think, because Lord Tennyson does not grasp the real meaning of the relative positions of man and woman in to-day’s society.

3. Tyranny and Liberty in the Abstract

With these in the abstract the poets have always been busy. They have denounced the former in measured language and unmeasured terms. Yet they have been known to refuse their signatures to petitions asking for justice on behalf of seven men condemned to death upon police evidence of the worst kind. They have sung paeans in praise of liberty in the abstract, or in foreign lands. Yet they have written hymns against Ireland and for the Liberal Unionists. Shelley has not, to use a forcible colloquialism, “gone back on himself.” When we read the Ode to Liberty, or the 1819 Ode for the Spaniards, or the tremendous Liberty of 1820, we have not the sense of uneasiness that we have when reading Holy Cross Day or The Litany of Nations. [Note to Reader: Marx puts Browning and Swinburne squarely in her sites with this reference]

LIBERTY

I.

The fiery mountains answer each other;

Their thunderings are echoed from zone to zone;

The tempestuous oceans awake one another,

And the ice-rocks are shaken round Winter's throne,

When the clarion of the Typhoon is blown.

II.

From a single cloud the lightening flashes,

Whilst a thousand isles are illumined around,

Earthquake is trampling one city to ashes,

An hundred are shuddering and tottering; the sound

Is bellowing underground.

III.

But keener thy gaze than the lightening’s glare,

And swifter thy step than the earthquake’s tramp;

Thou deafenest the rage of the ocean; thy stare

Makes blind the volcanoes; the sun’s bright lamp

To thine is a fen-fire damp.

IV.

From billow and mountain and exhalation

The sunlight is darted through vapour and blast;

From spirit to spirit, from nation to nation,

From city to hamlet thy dawning is cast,--

And tyrants and slaves are like shadows of night

In the van of the morning light.

This man is through and through a foe to tyranny in the abstract and in the concrete form.

Of course in much of his work the ideas that exercise a malevolent despotism over men’s minds are attacked in general terms. Superstition and empire in all their forms Shelley hated, and therefore he again and again dealt with them as abstractions from those forms. Superstition, or an unfounded reverence for that which is unworthy of reverence, was to him, at first, mainly embodied in the superstition of religion.

To the younger Shelley, l'infâme of Voltaire’s ecrasez l'infâme was to a great extent, as with Voltaire wholly, the priesthood. And the empire that he antagonised was at first that of kingship and that of personal tyranny. But even in his attacks on these he simultaneously assails the superstitious belief in the capitalistic system, and the empire of class. As time goes on, with increasing distinctness, he makes assault upon these, the most recent, and most dangerous foes of humanity. And always, every word that he has written against religious superstitions, and the despotism of individual rulers may be read as against economic superstition and the despotism of class. “The immense improvements of which by the extinction of certain moral superstitions [for moral we can also read economic] human society may be yet susceptible.” [Preface to Julian and Maddalo] [o].

4. Tyranny in the Concrete

We must pass over, with a mere reference only, the songs for nations — for Mexico, Spain, Ireland, England. Of his attacks upon Napoleon mention has been made. In the Mask of Anarchy, Castlereagh, Sidmouth, Eldon, are all personally gibbeted. In each case, not only the mere man but the infamous principle he represents is the object of attack. Just as the Prince Regent to Shelley was embodied princeship, and Napoleon embodied personal greed and tyranny, so Castlereagh (the Chief Secretary for Ireland before he was War Minister), was embodied war and government; Sidmouth, Home Secretary at the Peterloo time, embodied officialism, Eldon embodied Law. He is for ever denouncing priest and king and statesman:

Kings priests and statesmen, blast the human flower,

Even in its tender bud; their influence darts

Like sudden poison, through the bloodless veins

Of desolate society.— (Queen Mab) [p]

But he scarcely ever fails to link with these the basis on which nowadays they all rest — our commercial system. See the Queen Mab passage beginning: —

Commerce has set the mark of selfishness,

The signet of its all-enslaving power,

Upon a shining ore, and called it gold;

Before whose image bow the vulgar great,

The vainly rich, the miserable proud,

The mob of peasants, nobles, priests and kings,

And with blind feelings reverence the power

That grinds them to the dust of misery.

But in the temple of their hireling hearts

Gold is a living god and rules in scorn

All earthly things but virtue.

‘Since tyrants by the sale of human life

Heap luxuries to their sensualism, and fame

To their wide-wasting and insatiate pride,

Success has sanctioned to a credulous world

The ruin, the disgrace, the woe of war.

His hosts of blind and unresisting dupes

The despot numbers; from his cabinet

These puppets of his schemes he moves at will,

Even as the slaves by force or famine driven,

Beneath a vulgar master, to perform

A task of cold and brutal drudgery; -

Hardened to hope, insensible to fear,

Scarce living pulleys of a dead machine,

Mere wheels of work and articles of trade,

That grace the proud and noisy pomp of wealth! [q]

It is not for nothing that in Charles I the court fool puts together the shops and churches.“ The rainbow hung over the city with all its shops — and churches."[r] This leads us to our next point.

5. Shelley’s Perception of the Class-Struggle

More than anything else that makes us claim Shelley as a socialist is his singular understanding of the facts that to-day tyranny resolves itself into the tyranny of the possessing class over the producing, and that to this tyranny in the ultimate analysis is traceable almost all evil and misery. He saw that the so-called middle-class is the real tyrant, the real danger at the present day. Those of us who belong to that class, in our delight at Shelley’s fierce onslaughts upon the higher members of it, aristocrats, monarchs, landowners, are apt to forget that de nobis etiam fabula narratur- of us also he speaks. This point is of such importance that more quotations than usual must be taken to enforce it. From Edinburgh, in his first honeymoon he writes: — “Had he [Uncle Pilfold] not assisted us, we should still have been chained to the filth and commerce of Edinburgh. Vile as aristocracy is, commerce — purse-proud ignorance and illiterateness — is more contemptible [s].” From Keswick a few months later he writes of the Lake District: — “Though the face of the country is lovely, the people are detestable. The manufacturers, with their contamination, have crept into the peaceful vale, and deformed the loveliness of nature with human taint [t].” Or take this quotation from the Philosophic View of Reform (sic):

One of the vaunted effects of this system is to increase the national industry, that is, to increase the labours of the poor and those luxuries of the rich which they supply. To make a manufacturer work 16 hours when he only worked 8. To turn children into lifeless and bloodless machines at an age when otherwise they would be at play before the cottage doors of their parents. To augment indefinitely the proportion of those who enjoy the profit of the labour of others, as compared with those who exercise this labour.

Note how he quotes Godwin:

It was perhaps necessary that a period of monopoly and oppression should subsist, before a period of cultivated equality could subsist. Savages perhaps would never have been excited to the discovery of truth and the invention of art, but by the narrow motives whch such a period affords. But surely, after the savage state has ceased, and men have set out in the glorious career of discovery and invention, monopoly, and oppression cannot be necessary to prevent them from retiurning to a state of barbarism. (Godwin’s Enquirer, Essay II. See also Political Justice, Book VIII, Chapter 2).

At the end of a Keswick letter, 1811, to Miss Hitchener: — “The grovelling souls of heroes, aristocrats, and commercialists.” Even when he uses the phrase “privileged classes” in the Philosophic View of Reform [u], it is clear he is thinking of them as a whole in contradiction to the class destitute of every privilege. Two or three last quotations in this connection to show how he understood the relative positions, not only above and below but antagonistic of these two classes [v].

Ay, there they are-

Nobles, and sons of nobles, patentees,

Monopolists, and stewards of this poor farm,

On whose lean sheep sit the prophetic crows,

Here is the pomp that strips the houseless orphan,

Here is the pride that breaks the desolate heart.

These are the lilies glorious as Solomon,

Who toil not, neither do they spin, – unless

It be the webs they catch poor rogues withal.

Here is the surfeit which to them who earn

The niggard wages of the earth, scarce leaves

The tithe that will support them till they crawl

Back to her cold hard bosom. Here is health

Followed by grim disease, glory by shame,

Waste by lame famine, wealth by squalid want,

And England’s sin by England’s punishment.- Charles I, Act I, Scene 1

“Wales,” he wrote to Hookham on 3 December 1812 in an indignant mood,

“is the last stronghold of the moist vulgar and commonplace prejudices of aristocracy. Lawyers of unexampled villainy rule and grind the poor, whilst they cheat the rich. The peasants are mere serfs and are fed and lodged worse than pigs. The gentry have all the ferocity and despotism of the ancient barons, without their dignity and chivalric disdain of shame and danger. The poor are as abject as Samoyed, and the rich as tyrannical as bashaws.”

[See also] the chorus of priests in Act II, scene 2 of Swellfoot the Tyrant: “Those who consume these fruits through thee grow fat; those who produce these fruits through thee grow lean.” For a taste of the consequences to all and sundry, to whichever class they belong, of this class-antagonism a few stanzas from Peter Bell The Third :

Hell is a city much like London --

A populous and a smoky city;

There are all sorts of people undone,

And there is little or no fun done;

Small justice shown, and still less pity.

…….

There is a Chancery Court; a King;

A manufacturing mob; a set

Of thieves who by themselves are sent

Similar thieves to represent;

An army; and a public debt.

…….

Lawyers -- judges -- old hobnobbers

Are there -- bailiffs -- chancellors --

Bishops -- great and little robbers --

Rhymesters -- pamphleteers -- stock-jobbers --

Men of glory in the wars, --

Mary’s words may be quoted as summing up his position:

“Shelley loved the people, and respected them as often more virtuous, as always more suffering, and, therefore more deserving of sympathy than the great. He believed that a clash between the two classes of society was inevitable, and he eagerly ranged himself on the people’s side.” (Notes on the Poems of 1819. The Poetical Works of Percy Bysshe Shelley Edward Moxon 1874)

6. Shelley’s Understanding of the Real Meaning of Things

His acuteness of vision is not only seen in his marking off society into the two groups, but in his understanding the real meaning of phrases that are to most of us either formulae or cant. Let us take as many of these as space allows.

Anarchy. — Shelley saw and said that the Anarchy we are all so afraid of is very present with us. We live in the midst of it. Anarchy is God and King and Law in the Mask of Anarchy, and let us add is Capitalism.

Freedom. — The extraordinary statement that England is a free country was to Shelley the merest nonsense. “The death-white shore of Albion, free no more. … / The abortion with which she travaileth is Liberty, smitten to death.” (To — Corpses are Cold in the Tomb). And he understood the significant fact in this connection that those who talk and write of English freedom and the like know they are talking and writing cant. The hollowness of the whole sham kept up by newspaper writers, Parliamentary orators, and so forth, was as apparent to him sixty years ago as it is to-day to the dullest of us [aa].

'The tyrants of the Golden City tremble

At voices which are heard about the streets;

The ministers of fraud can scarce dissemble

The lies of their own heart, but when one meets

Another at the shrine, he inly weets,

Though he says nothing, that the truth is known;

Murderers are pale upon the judgement-seats,

And gold grows vile even to the wealthy crone,

And laughter fills the Fane, and curses shake the Throne.- Revolt of Islam

Custom. — The general evil of that custom which is to most of us a law, the law, the only law of life, he was never weary of denouncing. “The chains, the icy chains of custom (Queen Mab). The “more eternal foe than force or fraud, old custom” (Fall of Bonaparte). And with the denunciation of custom, followed merely because it is custom, is the noble teaching of self-mastery, and the poet’s contradiction of the statement that under the new regime men will be machines, uniformity reign, and individuality be dead [cc].

Nor happiness, nor majesty, nor fame,

Nor peace, nor strength, nor skill in arms or arts,

Shepherd those herds whom tyranny makes tame;

Verse echoes not one beating of their hearts,

History is but the shadow of their shame,

Art veils her glass, or from the pageant starts

As to oblivion their blind millions fleet,

Staining that Heaven with obscene imagery

Of their own likeness. What are numbers knit

By force or custom? Man who man would be,

Must rule the empire of himself; in it

Must be supreme, establishing his throne

On vanquished will, quelling the anarchy

Of hopes and fears, being himself alone.- Sonnet, Political Greatness

Cruelty of the governing class. — A tyrannical class like a tyrannical man stops at nothing in order to maintain its position of supremacy. No means are too insignificant, no weapon too ponderous. From the policeman’s “nark,” or spy not a member of the police force, to the machinery of a trial for treason, nothing comes amiss to the class that governs. Shelley knew what a mockery for the most part is a trial instituted by a government, whether in Ireland or in England. “A trial I think men call it” (Rosalind and Helen)

In June 1817, a few operatives rose in Derbyshire. A score of dragoons put down the Derbyshire insurrection, an insurrection there is reason to believe put up by a Government spy. On November 7th 1817, three men, Brandreth, Turner, Ludlam, “were drawn on hurdles to the place of execution, and were hanged and decapitated in the presence of an excited and horror-stricken crowd” (Dowden’s Life)

Against this judicial murder Shelley’s voice was lifted up, as it would be now in like case. For like cases are occurring, still occur in increasing numbers as the class struggle intensifies. In Ireland at Lisdoovarna, Constable Whelehan was murdered recently in a moonlighting raid. The raid had been planned by Cullinane, a Government spy. On Monday Dec. 12, 1887, one man was condemned to ten years’, four others to seven years’ penal servitude for an offence planned by a government spy. Against this sentence Shelley, were he alive, would, we are certain, protest. So would he have protested against the direct murders by the police at Mitchelstown, and Trafalgar Square. So would he have protested against the recent judicial murder in America of four men and the practical imprisonment for life of three others. The Chicago Anarchist meeting differed even from the Derbyshire insurrection of 1817. There was no rising, no talk of rising, no use of physical force by the people, no threat of it. Yet seven men were condemned on the evidence of the police, evidence that those who have read every word of it feel was not only insufficient to prove the guilt, but absolutely conclusive as to the innocence of the accused. Had Shelley been alive he would have been the first to sign the petition on behalf of the Chicago Anarchists.

Crime. — This phenomenon Shelley recognized as the natural result of social conditions. The criminal was to him as much a creature of the society in which the lived as the capitalist or the monarch. “Society,” said he, “grinds down poor wretches into the dust of abject poverty, till they are scarcely recognizable as human beings." (From Memoir of Shelley, William Michael Rossetti, p 96). In his literal discussions with Miss Hitchener, Shelley more than once asks whether with a juster distribution of happiness, of toil and leisure, crime and the temptation to crime, would not almost cease to exist. And much that is called crime was to Shelley (the Preface to Laon and Cythna is but one evidence) only crime by convention.

Property. The opinion of Shelley as to that which could be rightly enjoyed as a person’s own property and what could only be enjoyed wrongly, will be in part gathered from the following quotation:

But there is another species of property which has its foundation in usurpation, or imposture, or violence, without which, by the nature of things, immense possessions of gold or land could never have been accumulated.Labour, industry, economy, skill, genius, or any similar powers honourably and innocently exerted are the foundations of one description of property, and all true political institutions ought to defend every man in the exercise of his discretion with respect to property so acquired....

- A Philosophical View of Reform

We do not think the meaning of this quotation is strained if it is paraphrased in the more precise language of scientific socialism thus:

“A man has a right to anything that his own labour has produced, and that he does not intend to employ for the purpose of injuring his fellows. But no man can himself acquire a considerable aggregation of properly except at the expense of his fellows. He must either cheat a certain number out of the value of it, or take it by force.”

Again, note the conception of wealth in the Song to the Men of England: “The wealth ye find another keeps.” The source of all wealth is human labour, and that not the labour of the possessors of that wealth.

People of England ye who toil and groan,

Who reap the harvests which are not your own,

Who weave the clothes which your oppressors wear,

And for your own take the inclement air;

Who build warm houses....

And are like gods who give them all they have,

And nurse them from the cradle to the grave....- Fragment; To the People of England

As to that for which the working class work he quotes Godwin in the fifth note to Queen Mab:

“There is no real wealth but the labour of man….The poor are set to labour - for what? Not the food for which they famish: not the blankets for want of which their babies are frozen by the cold of their miserable hovels; : not those comforts of civilization without which civilized man is far more miserable than the meanest savage; oppressed as he is by all insidious evils, within the daily and taunting prospect of its innumerable benefits assiduously exhibited before him: no; for the pride of power, for the miserable isolation oif pride, for the false pleasures of the hundredth part of Society.”

Let us take as our last example of his understanding of the central position of socialism, a quotation to be found in a letter to Miss Hitchner, dated December 15th, 1811. Shelley is discussing the entailment of his estate: “that I should entail £120,000 of command over labour, of power to remit this, to employ it for beneficent purposes, on one whom I know not." (Letter to Elizabeth Hitchener, 15 December 1811)

We cannot expect even such a man as Shelley to have thought out in his time the full meaning of labour-power, labour, and the value of commodities. But undoubtedly he knew the real economic value of private property in the means of production and distribution, whether it was in machinery, land, funds, what not. He saw that this value lay in the command, absolute, merciless, unjust, over human labour. The socialist believes that these means of production and distribution should be the property of the community. For the man or company that owns them has practically irresponsible control over the class that does not possess them.

The possessor can and does dictate terms to the man or woman of that non-possessing class. “You shall sell your labour to me. I will pay you only a fraction of its value in wage. The difference between that value and what I pay for your labour I pocket, as a member of the possessing class, and I am richer than before, not by labour of my own, but by your unpaid labour.” This was the teaching of Shelley. This is the teaching of socialism, and therefore the teaching of socialism, whether it is right or wrong, is also that of Shelley. We claim him as a Socialist.

Tonight we have discussed the question whether he held our scientific principles. On some other occasion, if your courtesy allows us, we shall be glad to discuss the practical remedial measures that Shelley advocated, and the possible future that he anticipated. Here, again, we shall find him in harmony with modern socialistic thought. Finally, we propose on that future occasion to discuss certain of his chief works in the light of the investigation that has been commenced this evening.

The Peterloo Massacre and Percy Shelley by Paul Bond

Paul Bond’s essay is nothing less than a tour de force encapsulating and documenting Shelley’s reception by the radicals of his own era down to those of today. His article is wonderfully approachable, sparkles with erudition and introduces the reader to almost the entire radical dramatis personae of the 19th Century. I think it is vitally important for students of PBS to understand his radical legacy. And who better to hear this from than someone with impeccable socialist credentials: Paul Bond.

In the early autumn, my online “Shelley Alert” trip wire came alive with a link to an article published by Paul Bond on the World Socialist Web Site (“WSWS”) under the auspices of the International Committee of the Fourth International (“ICFI”). Paul, it turns out, is an active member of the Trotskyist movement and has been writing for the WSWS since its launch in 1998. It also turns out he is an ardent admirer of Percy Shelley. That someone like Paul would be interested in Shelley and that the ICFI would publish his article about Shelley did not surprise me in the least. Though I suspect it might arouse the curiosity of a goodly portion of Shelley’s current fan base.

Before we delve further into this, let’s find out exactly what the WSWS is? Understanding this may explain a lot:

The World Socialist Web Site is published by the International Committee of the Fourth International, the leadership of the world socialist movement, the Fourth International founded by Leon Trotsky in 1938.

The WSWS aims to meet the need, felt widely today, for an intelligent appraisal of the problems of contemporary society. It addresses itself to the masses of people who are dissatisfied with the present state of social life, as well as its cynical and reactionary treatment by the establishment media.

Our web site provides a source of political perspective to those troubled by the monstrous level of social inequality, which has produced an ever-widening chasm between the wealthy few and the mass of the world's people. As great events, from financial crises to eruptions of militarism and war, break up the present state of class relations, the WSWS will provide a political orientation for the growing ranks of working people thrown into struggle.

We anticipate enormous battles in every country against unemployment, low wages, austerity policies and violations of democratic rights. The World Socialist Web Site insists, however, that the success of these struggles is inseparable from the growth in the influence of a socialist political movement guided by a Marxist world outlook.

The standpoint of this web site is one of revolutionary opposition to the capitalist market system. Its aim is the establishment of world socialism. It maintains that the vehicle for this transformation is the international working class, and that in the twenty-first century the fate of working people, and ultimately mankind as a whole, depends upon the success of the socialist revolution.

You can learn more about them here.

For those of you familiar with the radical Percy Shelley, this will, of course, make sense. Shelley has been an inspiration to those on the left from the early 1800s. I have written extensively about this in my articles “My Father’s Shelley: A Tale of Two Shelleys”, “Percy Bysshe Shelley in Our Time” and “Jeremy Corbin is Right: Poetry Can Change the World”.

I think the fact that the WSWS has published an extensive article exploring Shelley’s radicalism is an important and salutary moment. It should help to reconnect Shelley to a new generation of radicals. The principal reason that Shelley remains relevant today is almost exclusively connected to his radicalism. His love poetry is exquisite and reminds us that PB was a three dimensional person. But there is an enormous amount of brilliant love poetry out there; and precious little radical poetry - having said that a great deal of Shelley’s love poetry is in fact a very radical variant of love poetry.

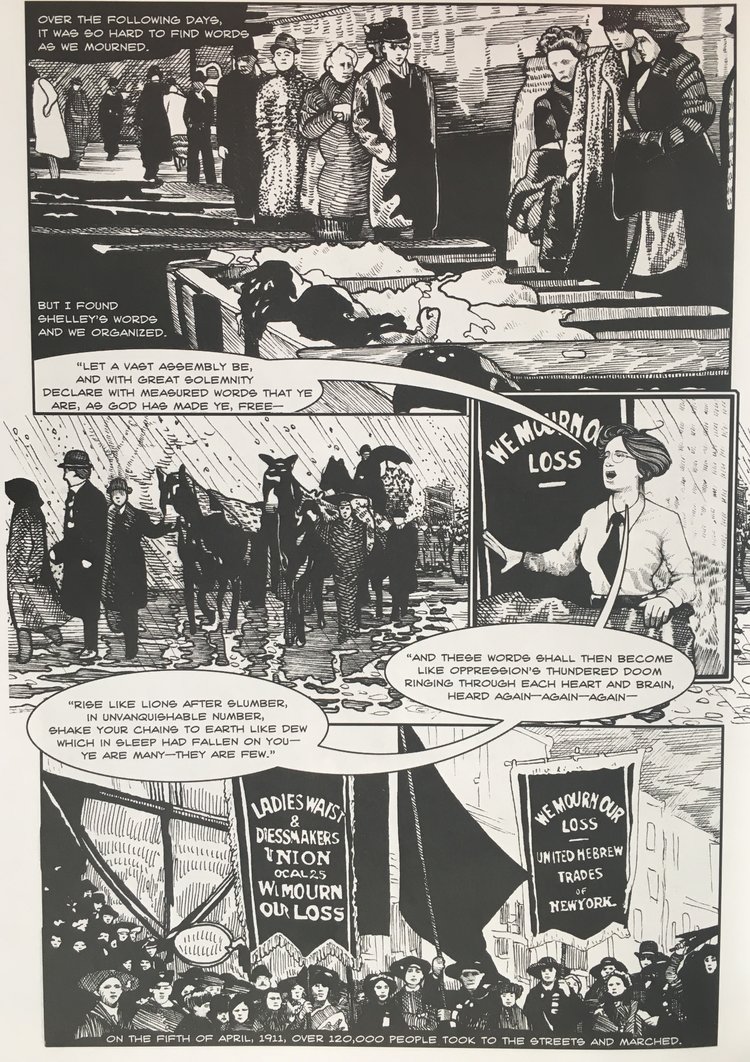

But it is Shelley’s radicalism that makes him stand out as a giant among his contemporaries. Little wonder then that Eleanor Marx proudly declaimed in a famous speech in 1888: “We claim his as a socialist.” Shelley’s radicalism inspired generations of activists and radicals; radicals who, explicitly inspired by Shelley, went on to change the world for the better. Is there a better example of this than the effect Shelley had on Pauline Newman, one of the founders of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union? You can read more about this in my article “The Story of the Mask of Anarchy: From Shelley to the Triangle Factory Fire”. And please read Michael Demson’s brilliant graphic novel of the same name. Links to buy it are in my article.

Two of the best biographies of Shelley were written by life-long members of the left. The first, Kenneth Neill Cameron (an avowed Marxist), penned The Young Shelley: Genesis of a Radical. The other, Paul Foot (the greatest crusading journalist of his generation), authored The Red Shelley. You can read Paul Foot’s spellbinding address to the 1981 International Marxism Conference in London here. It took me over two hundred hours to transcribe and properly footnote his speech!

For both Engels and Marx, Shelley was an inspiration:

Engels:

"Shelley, the genius, the prophet, finds most of [his] readers in the proletariat; the bourgeouise own the castrated editions, the family editions cut down in accordance with the hypocritical morality of today”

Marx:

The real difference between Byron and Shelley is this: those who understand them and love them rejoice that Byron died at thirty-six, because if he had lived he would have become a reactionary bourgeois; they grieve that Shelley died at twenty-nine, because he was essentially a revolutionist, and he would always have been one of the advanced guard of Socialism.

Eleanor Marx supplied the principle reason for these assessments of Shelley. She wrote,

More than anything else that makes us claim Shelley as a Socialist is his singular understanding of the facts that today tyranny resolves itself into the tyranny of the possessing class over the producing, and that to this tyranny in the ultimate analysis is traceable almost all evil and misery.

This grim portrayal of the tyranny faced by the citizens of Shelley’s and Marx’s eras has an equally grim, modern resonance. One need to look no further than Marxist-inspired writers such as Astra Taylor (The People’s Platform) and Shoshana Zuboff (The Age of Surveillance Capitalism) to come to grips with the fact that the situation has, if anything, got worse. Our modern “possessing class” of digital overlords threaten not simply to strip the people of their labour, but to turn our very lives into the raw materials that feed the rapacious, insatiable demands their modern “surveillance capitalism”.

However, let me turn the floor over to Paul Bond whose essay is something of a tour de force that encapsulates Shelley’s reception by the radicals of his era down to those of today. His article is wonderfully approachable, sparkles with erudition and introduces the reader to almost the entire radical dramatis personae of the 19th Century. I think it is vitally important for students of PBS to understand this radical legacy. And who better to hear this from than someone with impeccable socialist credentials: Paul Bond. You can follow Paul on Twitter @paulbondwsws and the World Socialist Web Site @WSWS_Updates.

The caption photo at top is of Eleanor Marx (middle) with her two sisters - Jenny Longuet, Laura Marx, father Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Eleanor was a champion of PBS.

The Peterloo Massacre and Shelley

by Paul Bond

This year marks the 200th anniversary of the Peterloo Massacre, a critical event in British history. On August 16, 1819, a crowd of 60,000 to 100,000 protestors gathered peacefully on Manchester’s St. Peter’s Field. They came to appeal for adult suffrage and the reform of parliamentary representation.The disenfranchised working class—cotton workers, many of them women, with a large contingent of Irish workers—who made up the crowd were struggling with the increasingly dire economic conditions following the end of the Napoleonic Wars four years earlier.

Shortly after the meeting began, local magistrates called on the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry to arrest the speakers and sent cavalry of Yeomanry and a regular army regiment to attack the crowd. They charged with sabres drawn. Eighteen people were killed and up to 700 injured.

On August 16 of this year the WSWS published an appraisal of the massacre.

The Peterloo Massacre elicited an immediate and furious response from the working class and sections of middle-class radicals.

The escalation of repression by the ruling class that followed, resulting in a greater suppression of civil liberties, was met with meetings of thousands and the widespread circulation of accounts of the massacre. There was a determination to learn from the massacre and not allow it to be forgotten or misrepresented. Poetic responses played an important part in memorialising Peterloo.

Violent class conflict erupted across north western England. Yeomen and hussars continued attacks on workers across Manchester, and the ruling class launched an intensive campaign of disinformation and retribution.

At the trial of Rochdale workers charged with rioting on the night after Peterloo, Attorney General Sir Robert Gifford made clear that the ruling class would stop at nothing to crush the development of radical and revolutionary sentiment in the masses. He declared: “Men deluded themselves if they thought their condition would be bettered by such kind of Reform as Universal Suffrage, Annual Parliaments, and Vote by Ballot; or that it was just that the property of the country ought to be equally divided among its inhabitants, or that such a daring innovation would ever take place.”

Samuel Bamford (1788–1872), 'The Radical', Silk Weaver of Middleton by Charles Potter

Samuel Bamford, a reformer and weaver who led a contingent of several thousand marchers to Manchester from the town of Middleton, said he spent the evening of the massacre “brooding over a spirit of vengeance towards the authors of our humiliation.” Bamford told the judge at his trial for sedition that he would not recommend non-violent protest again.

Workers took a more direct response, even as the military were being deployed widely against the population. Despite the military presence, and press claims that the city had been subdued, riots continued across Manchester.

Two women were shot by hussars on August 20. A fortnight after Peterloo, the most affected area, Manchester’s New Cross district, was described in the London press as a by-word for trouble and a risky area for the wealthy to pass through. Soldiers were shooting in the area to disperse rioters. On August 18, a special constable fired a loaded pistol in the New Cross streets and was attacked by an angry crowd, who beat him to death with a poker and stoned him.

There was a similar response elsewhere locally, with riots in Oldham and Rochdale and what has been described by one historian as “a pitched battle” in Macclesfield on the night of August 17.

Crowds in their thousands welcomed the coach carrying Henry Hunt and the other arrested Peterloo speakers to court in Salford, the city across the River Irwell from Manchester. Salford’s magistrates reportedly feared a “tendency to tumult,” while in Bolton the Hussars had trouble keeping the public from other prisoners. The crowd shouted, “Down with the tyrants!”

While the courts meted out sharper punishment to the arrested rioters, mass meetings and protests continued across Britain. Meetings to condemn the massacre took place in Wakefield, Glasgow, Sheffield, Huddersfield and Nottingham. In Leeds, the crowd was asked if they would support physical force to achieve radical reform. They unanimously raised their hands.

These were meetings attended by tens of thousands and they did not end despite the escalating repression. The Twitter account Peterloo 1819 News (@Live1819) is providing a useful daily update on historical responses until the end of this year.

A protest meeting at London’s Smithfield on August 25 drew crowds estimated at 15,000-40,000. At least 20,000 demonstrated in Newcastle on October 11. The mayor wrote dishonestly to the home secretary, Lord Sidmouth, of this teetotal and entirely orderly peaceful demonstration that 700 of the participants “were prepared with arms (concealed) to resist the civil power.”

The response was felt across the whole of the British Isles. In Belfast, the Irishman newspaper wrote, “The spirit of Reform rises from the blood of the Manchester Martyrs with a giant strength!”

A meeting of 10,000 was held in Dundee in November that collected funds “for obtaining justice for the Manchester sufferers.” That same month saw a meeting of 10,000 in Leicester and one of 12,000 near Burnley. In Wigan, just a few miles north of the site of Peterloo, around 20,000 assembled to discuss “parliamentary reform and the massacre at Manchester.” The yeomanry were standing ready at many of these meetings.

The state was determined to suppress criticism. Commenting on the events, it published false statements about the massacre and individual deaths. Radical MP Sir Francis Burdett was fined £2,000 and sentenced to three months’ imprisonment for “seditious libel” in response to his denunciation of the Peterloo massacre. On September 2, he addressed 30,000 at a meeting in London’s Palace Yard, demanding the prosecution of the Manchester magistrates.

Richard Carlile

Radical publisher Richard Carlile, who had been at Peterloo, was arrested late in August. He was told that proceedings against him would be dropped if he stopped circulating his accounts of the massacre. He did not and was subsequently tried and convicted of seditious libel and blasphemy.

The main indictment against him was his publication of Thomas Paine’s The Rights of Man. Like Bamford, Carlile also concluded that armed defence was now necessary: He wrote, “Every man in Manchester who avows his opinions on the necessity of reform should never go unarmed—retaliation has become a duty, and revenge an act of justice.”

In Chudleigh, Devon, John Jenkins was arrested for owning a crude but accurate print of the yeomanry charging the Peterloo crowd when Henry Hunt was arrested. A local vicar, a magistrate, informed on Jenkins, whose major “crime” was that he was sharing information about Peterloo. Jenkins was showing the print to people, using a magnifying glass in a viewing box. The charge against Jenkins argued that the print was “intended to inflame the minds of His Majesty’s Subjects and to bring His Majesty’s Soldiery into hatred and contempt.”

Against this attempt to suppress the historical record there was a wide range of efforts to preserve the memory of Peterloo. Verses, poems and songs appeared widely. In October, a banner in Halifax bore the lines:

With heartfelt grief we mourn for thoseWho fell a victim to our causeWhile we with indignation viewThe bloody field of Peterloo.

Anonymous verses were published on cheap broadsides, while others were credited to local radical workers. Many recounted the day’s events, often with a subversive undercurrent. The broadside ballad, “A New Song on the Peterloo Meeting,” for example, was written to the tune “Parker’s Widow,” a song about the widow of 1797 naval mutineer Richard Parker.

Weaver poet John Stafford, who regularly sang at radical meetings, wrote a longer, more detailed account of the day’s events in a song titled “Peterloo.”

The shoemaker poet Allen Davenport satirised in song the Reverend Charles Wicksteed Ethelston of Cheetham Hill—a magistrate who had organised spies against the radical movement and, as the leader of the Manchester magistrates who authorised the massacre, claimed to have read the Riot Act at Peterloo.

Ethelston played a vital role in the repression by the authorities after Peterloo. At a September hearing of two men who were accused of military drilling on a moor in the north of Manchester the day before Peterloo, he told one of them, James Kaye, “I believe that you are a downright blackguard reformer. Some of you reformers ought to be hanged; and some of you are sure to be hanged—the rope is already round your necks; the law has been a great deal too lenient with you.”

Percy Bysshe Shelley, Alfred Clint (after Amelia Curran) c. 1829

Ethelston was also attacked in verse by Bamford, who called him “the Plotting Parson.” Davenport’s “St. Ethelstone’s Day” portrays Peterloo as Ethelston‘s attempt at self-sanctification. Its content is pointed— “In every direction they slaughtered away, Drunken with blood on St. Ethelstone’s Day”—but Davenport sharpens the satire even further by specifying the tune “Gee Ho Dobbin,” the prince regent’s favourite. (These songs are included on the recent Road to Peterloo album by three singers and musicians from North West England—Pete Coe, Brian Peters and Laura Smyth.)

The poetic response was not confined to social reformers and radical workers. The most astonishing outpouring of work came from isolated radical bourgeois elements in exile.

On September 5, news of the massacre reached the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822) in Italy. He recognised its significance and responded immediately. Shelley’s reaction to Peterloo, what one biographer has called “the most intensely creative eight weeks of his whole life,” embodies and elevates what is greatest about his work. It underscores his importance to us now.

Franz Mehring, circa 1900

Even among the radical Romantics, Shelley is distinctive. He has long been championed by Marxists for that very reason. Franz Mehring famously noted: “Referring to Byron and Shelley, however, [Karl Marx] declared that those who loved and understood these two poets must consider it fortunate that Byron died at the age of 36, for had he lived out his full span he would undoubtedly have become a reactionary bourgeois, whilst regretting on the other hand that Shelley died at the age of 29, for Shelley was a thorough revolutionary and would have remained in the van of socialism all his life.” (Karl Marx: The Story of His Life, Harvester Press, New Jersey, 1966, p.504)

Shelley came from an affluent landowning family, his father a Whig MP. Byron’s continued pride in his title and his recognition of the distance separating himself, a peer of the realm, from his friend, a son of the landed gentry, brings home the pressures against Shelley and the fact that he was able to transcend his background.

Percy Bysshe Shelley’s childhood and education were typical of his class. But bullied and unhappy at Eton, he was already developing an independence of thought and the germs of egalitarian feeling. Opposed to the school’s fagging system (making younger pupils beholden as servants to older boys), he was also enthusiastically pursuing science experiments.

He was expelled from Oxford in 1811 for publishing a tract titled “The Necessity of Atheism.” That year he also published anonymously an anti-war “Poetical Essay on the Existing State of Things.” This was a fundraiser for Irish journalist Peter Finnerty, imprisoned for libel after accusing Viscount Castlereagh of mistreating United Irish prisoners. Long thought lost, a copy was found in 2006 and made available by the Bodleian Library in 2015.

Ireland was a pressing concern. Shelley visited Ireland between February and April 1812, and his “Address to the Irish People” from that year called for Catholic emancipation and a repeal of the 1800 Union Act passed after the 1798 rebellions. Shelley called the act “the most successful engine that England ever wielded over the misery of fallen Ireland.”

Shelley’s formative radicalism was informed by the French Revolution. That bourgeois revolution raised the prospect of future socialist revolutionary struggles, the material basis for which—the growth of the industrial working class—was only just emerging.

Many older Romantic poets who had, even ambivalently, welcomed the French Revolution as progressive reacted to its limitations by rejecting further strivings for liberty. Shelley denounced this, writing of William Wordsworth in 1816:

In honoured poverty thy voice did weave

Songs consecrate to truth and liberty, —

Deserting these, thou leavest me to grieve,