“What Art and Poetry Can Teach Us about Food Security”: A TED Talk on John Keats and John Constable by Professor Richard Marggraf Turley.

In his TED Talk “What art and poetry can teach us about food security,” Professor Richard Marggraf Turley dives deep into two classic works of British Romanticism: John Keats’ poem “To Autumn” (1819) and John Constable’s painting The Hay Wain (1821). Both present picturesque scenes from the English countryside that, on initial glance, appear far removed from the period’s volatile political debates. But Professor Turley encourages us to look closer. Both works, he suggests, bear the mark of one of the major social problems of the time: hunger. Both Keats and Constable lived through times in which the English countryside underwent considerable change: food prices, growing at a rapid rate, brought wealthy speculators to England’s agricultural areas, many of whom bought up large swaths of the land. The results were devastating: families who had tilled the ground for generations found themselves pushed off the land as early versions of industrial farming took root. Mass unemployment ensued, inflated food prices soared even higher, and much of the country went hungry.

Constable's The Hay Wain (1821), completed a year after the publication of Keats' great poem, "To Autumn"

As Professor Turley fleshes out the deeper layers of each work, he shows us how even the most seemingly apolitical subjects, like a solitary artist’s contemplation of nature, bear the weight of major political controversies. He also shows us how these artists can help us to have our own conversations about hunger and poverty today: in our time as in the Romantic period, many in the middle and lower classes regularly struggle to put food on the table. Have a listen to Professor Turley’s talk to learn more about how writers like Keats and painters like Constable can help us face our greatest obstacles, as food waste, soil erosion, and economic turmoil create a whole new set of hunger problems in the twenty-first century.

Richard Marggraf Turley is Aberystwyth University's Professor of Engagement with the Public Imagination. He has published and taught widely on the Romantics, and he is one of the organisers of the International Keats Conference. He is also a blues guitarist and velocipedist.

Ginevra: A Shelley-Inspired Animation by Tess Martin and Max Rothman. By Jonathan Kerr

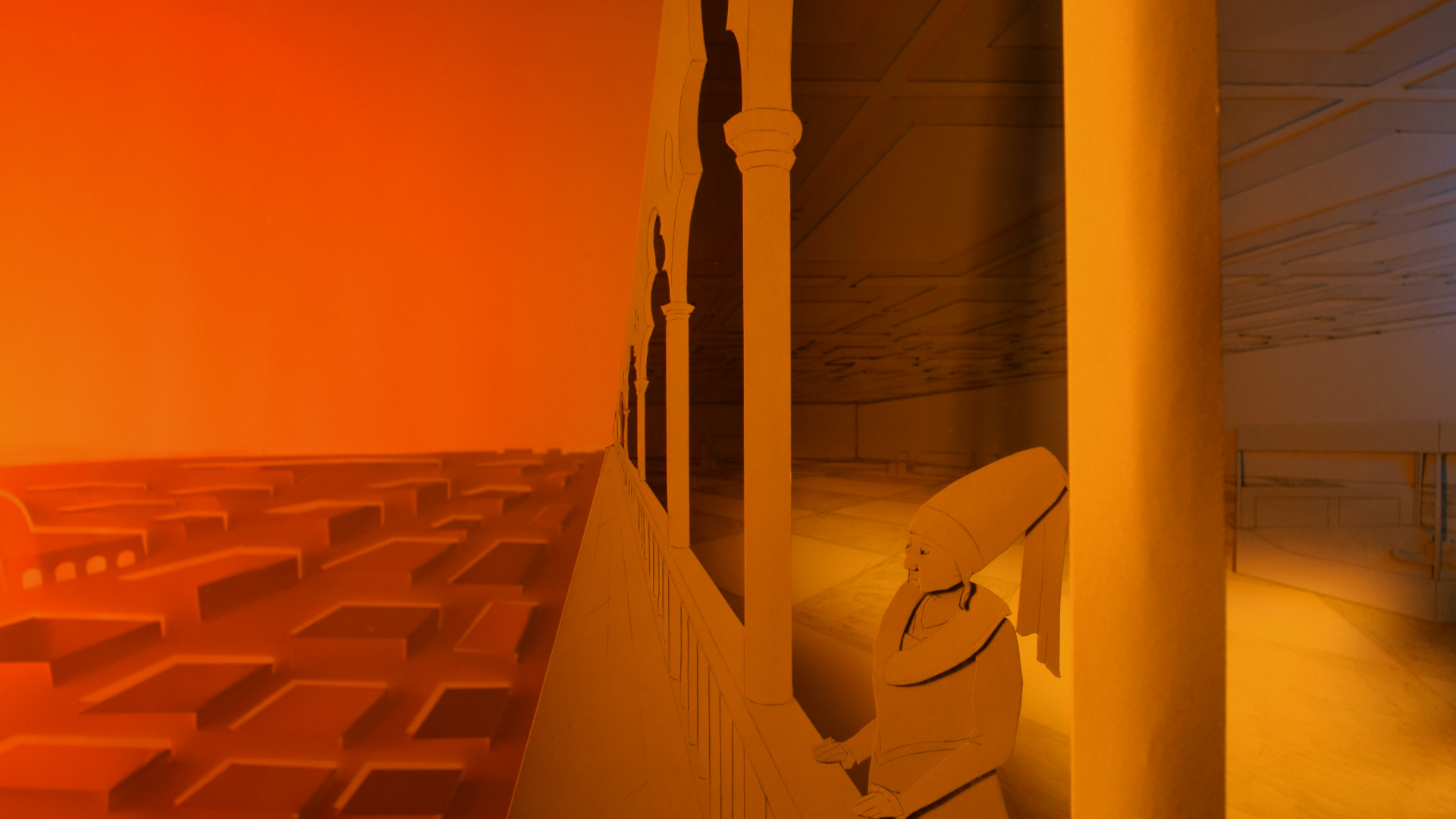

I recently had the opportunity to sit down and talk with two filmmakers who have contributed something truly remarkable to the Shelley revival. Tess Martin and Max Rothman have created Ginevra (2017), a short animated film that beautifully recreates one of Percy’s poems (also titled “Ginevra”) about the marriage and death of a young Italian woman. Created in cut-out animation with a voiceover narrator reciting lines from the original poem, Ginevra reimagines Shelley’s story, picking up where blanks appear in the unfinished manuscript. As it does so, it takes Shelley’s story in a bold, imaginative new direction.

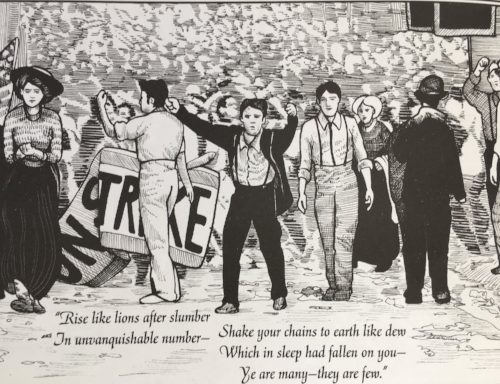

As Shelley enthusiasts, we are living through very exciting times. The bicentenaries marking the Shelleys’ legendary summer at Villa Diodati, the publication of Frankenstein, the Peterloo Massacre, and the composition of some of P.B.’s finest writing have brought with them a whole slew of Shelley commemorations. The 2017 Shelley Conference—the first of its kind since 1992—offered fascinating new perspectives for understanding the Shelleys and the issues that most dearly affected them. New graphic novels by Michael Demson and “Polyp” recreate some of the most pivotal events shaping Percy’s life and writing; feature-length films (here and here), a television production, and even a fashion show have found innovative ways to reimagine the Shelleys' life and times. Whether you’re a Shelley specialist, a costume-drama fanatic, a history buff, or a casual reader, the wave of interest in the Shelleys will certainly have something for you!

Michael Demson's graphic novel Masks of Anarchy (2013) tells the story of the Peterloo Massacre and Shelley's response to it.

I recently had the opportunity to sit down and talk with two filmmakers who have contributed something truly remarkable to the Shelley revival. Tess Martin and Max Rothman have created Ginevra (2017), a short animated film that beautifully recreates one of Percy’s poems (also titled “Ginevra”) about the marriage and death of a young Italian woman. Created in cut-out animation with a voiceover narrator reciting lines from the original poem, Ginevra reimagines Shelley’s story, picking up where blanks appear in the unfinished manuscript. As it does so, it takes Shelley’s story in a bold, imaginative new direction.

I want to get to what Tess and Max had to say about "Ginevra"—what attracted them to Shelley, and what made them want to recreate this little-known poem. First, however, I want to introduce you to Ginevra herself, and to the legend that has fascinated storytellers from the Renaissance to the present.

Over the centuries, the story of Ginevra has come together like an old wall, the kind you might see lining the streets of an ancient city. Early stories—our wall’s base—first emerge over the Renaissance as a Florentine legend about a woman named Ginevra degli Almieri. There were many stories of Ginevra circulating, but the most important one to Shelley, and the animation film it inspired, comes down to us from Marco Lastri's L'Osservatore Fiorentino, first published in 1776-78. In Lastri's telling, Ginevra is betrothed by her father to a nobleman named Francesco Agolanti. Ginevra lives unhappily with her husband for several years until, one day, relatives find her collapsed and unresponsive. Thinking that Ginevra has died, relatives arrange a funeral and lay the young woman to rest in a cathedral. Ginevra is not dead, however; after awakening in her tomb, Ginevra manages to escape the crypt and quickly heads for home. What follows is surprisingly comic by the standards of urban legends: thought to be a ghost by both her husband and father, Ginevra is refused entry to both households and left an exile on Florence’s streets. She eventually visits Antonio, her former lover, who promptly takes the destitute woman in. Ginevra’s husband, soon informed of the recent turn of events, angrily petitions a Florentine court for restitution; however, since Ginevra had been declared legally dead, the marriage had already been nullified. Ginevra, meanwhile, has been given “second life,” and is free to remarry. She and Antonio marry and, according to Lastri's story, live happily ever after.

"Ginevra degli Almieri," a Renaissance urban legend, tells of the burial and "afterlife" of a Florentine woman. (Caption: Antoine Wiertz, The Premature Burial, 1854.)

Mary and Percy read Lastri's strange tale, in addition to other Italian legends about premature entombment and "resurrection." A cursory glance through whatever Shelley volume may reside in your library will give you a sense of just how deep ran Shelley's appreciation for Dark Age tales of horror and the macabre!

As Shelley engages with this particular story, he transforms it in really interesting ways. Unlike Lastri's heroine, Shelley’s Ginevra is not a victim of superstition or medical malpractice; rather, she dies under mysterious circumstances. Shelley writes Ginevra's life and death in a deliberately ambiguous and open-ended fashion: is Ginevra murdered by her husband on account of her love affair with Antonio? Does Ginevra, dejected about her forced marriage, choose to end her life? However we choose to read Ginevra's story, it bears the mark of some of Shelley's most characteristic preoccupations as a writer: the need to confront the weight that age-old customs and their institutions place upon people's self-conception, worldview, and decisions; the challenges involved overcoming power structures and living a self-determined life; and the especially oppressive conditions that European societies placed upon the most vulnerable, like (in Ginevra's case) women and the young.

Whatever we choose to make of Ginevra's mysterious fate, the dirge recited at Ginevra's funeral hints at some sort of rebirth for the heroine. Like Lastri's version of the story, Shelley’s poem gestures to a second life for Ginevra, then, although what that might mean is left unclear. As Shelley cryptically writes,

"She is still, she is cold

On the bridal couch,

One step to the white deathbed,

And one to the bier,

And one to the charnel—and one, oh where?"

Ginevra (2017), the latest addition to our wall, weaves the Renaissance urban legend and the Romantic poem together. In a way, it “completes” Shelley’s poem by filling in scenes where the manuscript breaks off. But it also contributes something totally original to this centuries-old tale. Ginevra might strike you as both very historical and very current. I won’t give you many details about the short film, since I don't want to spoil it; you should watch it for yourself and form your own experience with this little gem. But I will give you a little bit of the discussions I’ve recently had with two people from the Ginevra team: Tess Martin, the director, and Max Rothman, the producer. Tess and Max opened up about what drew them to Shelley's little-known poem and why they were inspired to complete Ginevra's transition from a bit of Italian folklore, to a forgotten classic of British Romanticism, to a work of animated film.

Ginevra came together with the spirit of collaboration in mind—fitting, given the story’s layered history. Shelley's poem first drew the interest of Max, a film producer who previously worked with NBC’s news department. He mentioned to me that the poem was perfect for the Campfire Poetry Project, a new initiative he’s working on that brings older poetry together with new art forms like animation, painting, and dance. The poem has a brooding atmosphere that Max recognized would lend itself nicely to visual illustration (the beautiful stills included below give you a nice idea of this); the unfinished poem also has a number of gaps that could free up an animator to take the story in interesting new directions.

A still from Ginevra.

Max brought the poem up with Tess, the director behind Ginevra. Shelley’s poem was one of 10 or 12 they discussed working on together. She, like Max, was attracted to the poem’s cliff-hanger ending. “It is interesting to think how Shelley would have finished his poem had he himself not died suddenly at sea,” she said. “In his poem, a bride dies on her wedding night. Would he have had her resurrect?”

More from Ginevra.

After doing some research into Shelley’s “Ginevra” and the Italian folk stories that inspired it, Tess set to work adding her own unique angle to the story. Ginevra’s fate is very different in all three versions, but all three also deal, in one way or another, with Ginevra’s rebirth into a new kind of life. I brought up with Tess how preoccupied Shelley was with forms of Old World tyranny, and particularly with the violence that marriage institutions permitted men to inflict against women and children—The Cenci, “Ginevra,” and Queen Mab all come to mind. Is this something that Tess wanted to explore as she depicted Ginevra’s death and rebirth? “Definitely there’s a feminist angle,” she told me, something that Tess also noticed in the Renaissance urban legend. In the original story, Ginevra finds a way to avoid her forced marriage, although “she still had to marry someone”; by contrast, something far more independent and strange awaits Tess’s Ginevra.

Max noted how interested he is in the overlap between the older kinds of stories told by poets and the newer techniques adopted by today’s filmmakers. “They’re working with the same storytelling archetypes we use now,” he says. In Ginevra’s case, the overlap is thematic as well. There’s something sadly current about Tess and Max’s animation, despite the old feel of Shelley’s language and the film’s Renaissance setting. All fairy-tales (and Ginevra certainly has a fairy-tale quality, despite its R-rating!) are timeless to one degree or another, since they are “about people trying to escape oppressors and be free,” Tess says.

Tess mentioned to me that for version of Ginevra's story, she wanted to evoke the tale's original Renaissance setting.

Tess had Blade Runner (1982) in mind when creating Ginevra.

When I asked Tess about whether she had any other films in mind when making Ginevra, she gave me an interesting one: Blade Runner. It surprised me initially, but it made more sense the more I thought about it. In Blade Runner, the more we look at the hyper-modern (or futuristic) problems encountered by the movie’s central figures, the more we realize that these problems—colonialism, gender inequality, the hubristic desire for too much knowledge or power—are in fact very old ones. It is just this interplay between history and the present that might have attracted Shelley to the first stories told about Ginevra degli Almieri. Shelley’s writing often captures the paradoxical sense that his period is both liberated from, and dominated by, history. This paradox also follows the story of Ginevra through the ages: a proto-feminist and victim of Old World violence, her story evokes both hope and fear about people's prospects for leading self-determined lives and creating change in the world.

How then would Shelley have finished his poem? Would Ginevra have emerged triumphant, liberated from her time and evolved into something "rich and strange" (to borrow lines from Shelley's epitaph)? Would Shelley have given us "Ginevra Unbound"? Or would the poem capture the possibility that history might be too strong for any one hero to combat on their own?

I, for one, am happy that these questions are left unresolved in Shelley's great, mysterious poem. From the gaps and fragments of Shelley's original have emerged new, exciting ways of engaging with his story. Tess and Max have returned to a classic Shelley poem, but they have also taken their heroine into bold and unpredictable territory. Looking back, in other words, has enabled them to imagine a new kind of future—for Ginevra, certainly, and perhaps for others as well. This, I think, would have made the Romantic rebel proud.

Jonathan Kerr is a university teacher and writer. He has recently completed his PhD from the University of Toronto with specialization in Shelley and other Romantics.

Tess Martin is an animator and film writer based in the Netherlands. She has received numerous grants, prizes and artist residencies in support of her work, which can be seen at festivals and in galleries worldwide. Learn more about Tess’ work here.

Max Rothman is a producer, editor, and filmmaker based in New York. He is the founder of Monticello Park Productions, a film production company that works with established and emerging auteurs from around the world. You can find more about Max’s work here.

Since its premiere in 2017, Ginevra has screened at a number of prominent film festivals and won several awards in film animation. Watch and learn more about Ginevra here.

"Ginevra," left incomplete on Shelley's death in 1822, was first published in Posthumous Poems (1824), a collection of Percy's poetry put together by Mary Shelley. You can read the poem in its entirety here.

Professor Michael Demson on the Real-World Impact of Shelley's Writing. A Summary by Jonathan Kerr.

Shelley’s poetry, Michael Demson argues, gave American workers a kind of writing that helped them to understand the political and economic forces to which they were subjected. “The Mask of Anarchy” was especially important in this context: written in easy-to-understand language, this poem attacks the power imbalances that helped to keep the powerful empowered and the poor disenfranchised. The conditions that made this sort of thing possible when Shelley lived—corrupt legal systems, unequal access to education, and working conditions that kept labourers underpaid and vulnerable—remained largely unchanged a century later in America. This is why, Demson alleges, a poem like “The Mask of Anarchy” could act as such a catalyzing force for New York’s industrial workers, not only providing common people with a language for understanding their problems, but also helping them to build a sense of community.

Michael Demson, “‘Let a great Assembly be’: Percy Shelley’s ‘The Mask of Anarchy,’” published in The European Romantic Review, Volume 22, Number 5, p. 641-665

a précis by Jonathan Kerr.

In “‘Let a great Assembly be,'” Michael Demson unearths powerful evidence for the real-world impact of Shelley’s writing. Many literary scholars throughout history have dismissed Shelley’s politics as naïve, out-of-touch, or disingenuous, a kind of adolescent posturing. By contrast, Demson not only reasserts Shelley’s deep commitment to radical causes; he also demonstrates that Shelley’s political poetry had concrete social impact in the decades and centuries following the poet’s death. Far from an elite writer speaking only to learned readers, Shelley used his poetry to expose and redress problems afflicting everyday people—and this effort paid off.

The International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union (ILGWU), whose labour activism was influenced by Shelley's writing.

Demson makes his case by investigating the role Shelley’s writing played in America’s early twentieth-century unions, and New York’s International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU) in particular. Shelley’s poetry, Demson argues, gave American workers a kind of writing that helped them to understand the political and economic forces to which they were subjected. “The Mask of Anarchy” was especially important in this context: written in easy-to-understand language, this poem attacks the power imbalances that helped to keep the powerful empowered and the poor disenfranchised. The conditions that made this sort of thing possible when Shelley lived—corrupt legal systems, unequal access to education, and working conditions that kept labourers underpaid and vulnerable—remained largely unchanged a century later in America. This is why, Demson alleges, a poem like “The Mask of Anarchy” could act as such a catalyzing force for New York’s industrial workers. In Demson’s words, “the language of ‘The Mask of Anarchy’ became the common tongue among workers, not only articulating their miserable conditions in a manner that brought them together, but also providing the terms of and for their protest” (651). As Demson suggests here, a poem like “The Mask of Anarchy” not only offered common people a language for understanding their problems, but also helped workers to build a sense of community from culture and shared political goals.

Pauline Newman (), whose labour activism was influenced by "The Mask of Anarchy."

No figure in New York’s labour movement was more influential than Pauline Newman (1887-1986) for organizing workers and forcing workplace reform. At the same time, no writer was more important to Newman’s efforts than Percy Shelley. Newman, born in modern-day Lithuania to Jewish parents, fought anti-Semitic and misogynistic laws in her home country and America to win herself an education; following the Newmans’ move to New York City’s Lower East Side, she worked at several factories in order to help her family stay afloat; in fact, Newman was just nine years old when she took her first job. This experience gave her a first-hand understanding of the dismal conditions afflicting lower-class workers. As she worked long hours in New York’s factory grind, Newman taught herself English and quickly became interested in Socialism. While still in her early twenties, Newman rose to prominence as an organizer for the ILGWU, helping to lead the cause toward unionization in America’s blue-collar industries. It was around this time that Newman also became introduced to Shelley’s writing by an English professor at New York’s City College.

As Demson shows, Newman believed that true change for workers required not only new laws and systems of regulation, but education and literacy: these were the tools required for achieving a cultural (and not merely legislative) sea change. Newman helped to organize union reading groups that brought workers (and particularly female workers) together. Shelley was an especially popular author for these reading groups. This is because poems like “The Mask of Anarchy” addressed the major problems affecting labourers in Shelley’s time and in Newman’s: low pay, dangerous working conditions, and degrading treatment by employers. But by bringing people together through culture, Demson argues, Shelley also inspired class pride and even helped to build bridges between New York’s immigrant populations.

Pauline Newman was not the only influential unionist who championed Shelley. Demson points out that Shelley’s writings were also extremely popular subjects of study at the Workers’ University, an institution founded in 1918 by the ILGWU. Demson writes that “Shelley’s poetry was taught at the… Workers’ University to hundreds of laborers as the first poet in history to voice their struggles” (646). This helped to build the growing image of Shelley as a poet of the people, and his writings increasingly acted as a source of education, community-building, and protest for workers across America. Shelley’s influence on these circles of labour organizers and reformers leads Demson to a powerful conclusion: “‘The Mask of Anarchy’ played a very real role to bring about substantive change in the… realities of countless laborers in a time of political crisis” (646).

Cell from Michael Demson's, Masks of Anarchy

Demson argues that Shelley was not writing primary for the downtrodden of his own time: rather, “Shelley may have conceived of the reception of ‘The Mask of Anarchy,’ and his commitment to reform, in a larger… historical framework” (644)—that is to say, when Shelley wrote, he may have had in mind future communities of readers, taking up his revolutionary call generations after his own death. Shelley’s readers in the workers’ unions and universities explored by Demson answered such a call. As they did so, they confirmed Shelley’s view that the truth of a work like “The Mask of Anarchy” means that its power will be felt not only in its own time, but in the decades and centuries after.

Want more? In Masks of Anarchy, a graphic novel published by Verso Books, Demson gives us a fictionalized account of how Shelley’s great poem inspired reformers and changed history. You can find it at local book stores everywhere; you can also find more about Demson’s novel here.

Jonathan Kerr has recently obtained his PhD in English from the University of Toronto. His research explores changing ideas about nature and human nature in the writings of Shelley and his contemporaries. He is currently at Mount Alison University on a post doc.

- Mary Shelley

- Mask of Anarchy

- Anna Mercer

- Coleridge

- An Address to the Irish People

- Richard Carlile

- Jonathan Kerr

- George Bernard Shaw

- Chartism

- Diodati

- Timothy Webb

- Mary Wollstonecraft

- Defence of Poetry

- William Wordsworth

- Queen Mab

- Michael Gamer

- Maria Gisborne

- World Socialism Web Site

- Theobald Wolfe Tone

- Butcher's Dozen

- Percy Shelley

- Freidrich Engels

- Milton

- Blade Runner

- ararchism

- Paul Bond

- Rosa Luxemburg

- Masks of Anarchy

- Keats-Shelley Review

- John Keats

- Leigh Hunt

- A Defense of Poetry

- Humphry Davy

- perfectibility

- Henry Hunt

- Paradise Lost

- Political Justice

- Shelley Society

- Polidori

- Necessity of Atheism

- David Carr

- The Last Man

- Harriet Shelley

- Eleanor Marx

- Industrial Workers of the World

- A Philosophical View of Reform

- Joe Hill

- The Easter Rising

- When the Lamp is Shattered

- Richard Margraff Turley

- Henry Salt

- Buxton Forman

- Lord Sidmouth

- Valperga

- Daisy Hay

- Frankenstein

- Peterloo

- Michael Demson

- William Godwin

- Byron

- Pauline Newman

- Mutability

- Epipsychidion

- Thomas Paine

- Mont Blanc

- Mark Summers

- Paul Foot

- free media

- Daniel O'Connell

- Vindication of the Rights of Women

- Ginevra

- Jacqueline Mulhallen

- Edward Dowden

- Robert Southey

- Chamonix

- James Connolly

- Edward Aveling

- Claire Clairmont

- Levellers

- England in 1819

- Lynn Shepherd

- To Autumn

- Alastor

- Ozymandias

- Francis Burdett

- Kenneth Neill Cameron

- Thomas Kinsella

- Tess Martin

- Geneva

- Proposal for an Association

- Cenci

- Kathleen Raine

- Richard Emmet

- Martin Bodmer

- Sonia Liebknecht

- Radicalism

- Keats-Shelley Association

- Trotsky

- Isabel Quigley

- Alien