Shelley Lives - Taking the Revolutionary Poet Shelley to the Streets.

Last fall Mark Summers did something absolutely fantastic: HE ACTUALLY TOOK SHELLEY'S POETRY TO A STREET PROTEST. Read his moving account of his experience. There are lessons for all of us in his experience. I think Mark's article is one of the most important I have published - and every student or teacher of Shelley needs to pay close attention to what Mark did. The revolutionary Shelley would be ecstatic!

One of the goals of my site is also to gather together people from all disciplines and walks of life who are interested in Shelley. One such person is Mark Summers. You have encountered his writing on my site: The Political Fury of Percy Bysshe Shelley and Revolutionary Politics and the Poet. Mark Summers came late to Shelley - he first encountered him when the newly discovered Poetical Essay on the Existing State of Things was published for the first time in late 2015. But he was a quick learner, and I think he has a better sense of Shelley than many people who have been studying him for thirty years.

Mark is an e-Learning specialist for a UK Midlands based company and a musician specializing in experimental and free improvised forms. An active member of the Republic Campaign which aims to replace the UK monarchy with an accountable head of state, Mark blogs at at www.newleveller.net which focuses on issues of republicanism and radical politics and history. You can also find him on Twitter @NewLeveller.

Mark's writing has a vitality and immediacy which is exhilarating. What I love most about it is his ability to put Shelley in the context of his time, and then make what happened then feel relevant now. Both Mark and I sense the importance of recovering the past to making sense out of what is happening today. With madcap governments in England and the United States leading their respective countries toward the bring of authoritarianism, Shelley's revolutionary prescriptions are enjoying something of a renaissance; and so they should, we need Percy Bysshe Shelley right now!

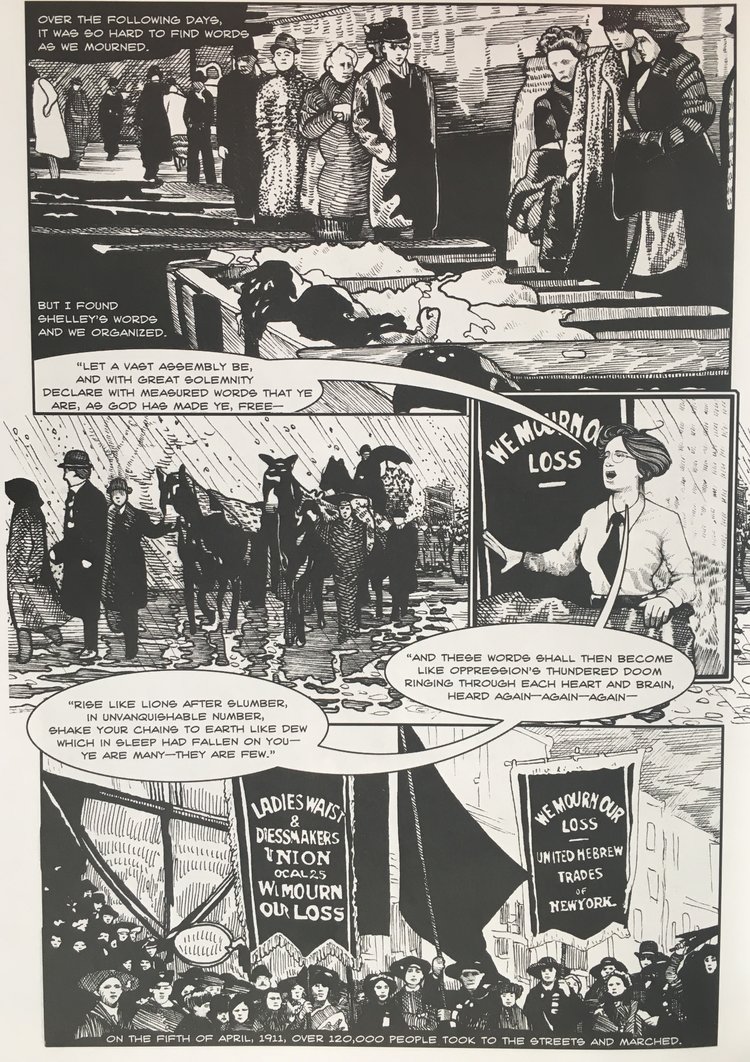

One of Mark's dreams was to "take Shelley to the streets". There has been a long history of this, most recently during the Occupy Wall Street demonstrations. Then there was the early 20th Century union organizer Pauline Newman who deployed Shelley's poetry to great effect while founding the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union. I wrote about that in Masks of Anarchy by Michael Demson. I also recently reported on a highly unusual but effective use of Shelley's The Mask of Anarchy by English fashion designer John Alexander Skelton: Shelley Storms the Fashion World With Mask of Anarchy.

Well, last fall Mark Summers did something absolutely fantastic: HE ACTUALLY TOOK SHELLEY'S POETRY TO A STREET PROTEST. What follows is his moving account of his experience. There are lessons for all of us in his experience - including some very practical ones such as the correct use of a megaphone! I think Mark's article is one of the most important I have published - and every student or teacher of Shelley needs to pay close attention to what Mark did. It is easy for us to chat amiably about Shelley in seminar rooms or at conferences, to comment on our FaceBook pages or Twitter accounts - it is entirely another thing altogether to go to a protest and read Shelley aloud to demonstrators. Yet this is EXACTLY how I think Shelley would have wanted his poetry to be heard. The closest I have come to Mark's experience pales in comparison: I have taken to working Shelley into all my speeches. And what I have taken away from the experience is very similar to what Mark learned. So grab a coffee or a whiskey (or both) and settle in for a terrific read.

Suits, Poetry and Megaphones; My Experience with Shelley at #TakeBackBrum 2016 - by Mark Summers

In previous posts and articles I have described some of the ways in which the works of the great philosopher and poet Percy Bysshe Shelley have stood the test of time. My central point is that beneath the establishment whitewash, Shelley’s work is as relevant to radical politics now as it was two centuries ago; his concerns are our concerns. So it has been an idea of mine to take Shelley back to where he belongs – the streets of Britain, via a megaphone!

Protest and Poetry

This year the Conservative Party held its annual conference in central Birmingham between the 2nd and 5th October. As a means of protesting the Government’s austerity measures which has seen the poorer and more vulnerable members of society paying for the excess and incompetence of a broken financial system, the People’s Assembly organized a weekend of protest in the city. With our presence at the start of the Sunday protest march, the Birmingham branch of Republic Campaign drew attention to the fact that monarchy is one of the few institutions completely shielded from the cuts inflicted on the rest of society. This presented the perfect opportunity to debut my ‘Street Shelley’ plan especially as between 10,000 and 20,000 people would be queuing up to march past.

Deciding that road transport and parking would be a nightmare I took the train into Birmingham. It was an almost surreal experience as protestors laden with banners, flags and leaflets rubbed shoulders (literally in the case of a crowded train) with conference delegates in suits and carefully coiffured hair!. I had chosen my poems beforehand, England in 1819, Masque of Anarchy and Poetical Essay on the Existing State of Things. Three of the most radical and hard hitting of Shelley’s pieces. The major problem I needed to overcome was a total lack of experience of poetry recitation! My original plan had been to include some stanzas from the great chartist poets such as Gerald Massey.

Gerald Massey, Chartist, mid 1850's. From Samuel Smiles' Brief Biographies, 1876.

But powerful as these works are (I must get around to writing about them very soon) they proved far trickier for a novice to handle than the fluid lines of Shelley. Considering the fact that I was also using a megaphone in a restless crowd I decided to play safe by letting the words of the poems do the work.

Learning Quickly

As a shorter sonnet, England in 1819 was suitable for reading in its entirety. But the longer poems needed more careful consideration. One of the delights of reading both Mask of Anarchy and Poetical Essay at your leisure is the way in which Shelley structures his material, diverting now this way, now that way to provide background and develop his theme. This would simply not work for a shifting crowd where the aim is for impact in an environment with competing demands for attention. The best plan would be to choose portions in the hope of hooking people in to discover more. Selecting the material from Mask of Anarchy was a relatively straightforward task with Shelley deftly creating distinct points of tension within its tripartite structure. This means that groups of 10 or 12 stanzas are distributed through the poem which have both internal coherence and impact. So, for example, the following section works as a unit, especially as it contains one the most famous lines in radical poetry "Ye are many—they are few."

Men of England, heirs of Glory,

Heroes of unwritten story,

Nurslings of one mighty Mother,

Hopes of her, and one another ;

Rise like Lions after slumber

In unvanquishable number.

Shake your chains to earth like dew

Which in sleep had fallen on you—

Ye are many—they are few.

…….

[Through to]

……

Paper coin—that forgery

Of the title-deeds, which ye

Hold to something from the worth

Of the inheritance of Earth.

’Tis to be a slave in soul

And to hold no strong control

Over your own wills, but be

All that others make of ye.

Reciting the poetry was an experience with very steep vertical learning curve. For example, I quickly discovered that it was more effective to actually turn down the megaphone volume and raise the volume of my voice. In this way I realized just how well it works as a visceral language with a weight capable of projection. Lines such as

’Tis to see your children weak

With their mothers pine and peak,

could be delivered with energy and passion, the whole thing becoming quite a cathartic experience. Strangely, despite having spent much time over the past few months with these works I discovered that the meaning of a few words and lines were less obvious than I originally thought.

Image from Michael Demson's Masks of Anarchy, a brilliant graphic novel that can be purchased here.

Shelley Lives!

The reaction of the protestors was mixed. Many of them were simply bemused, but I did draw a small round of applause at one point. More gratifyingly were the people who came up to me and enquired further about the poems which fulfilled a central aim of piquing interest. One person in particular wanted me to place Shelley in the historical sweep of radical dissent. The surprising and depressing fact was that he was an English History graduate for whom radicalism was presented as a half-hearted account of Marxism in the 19th Century! The majestic sweep and variety of radical thought over four centuries had largely passed him by – what an indictment of the education system.

Will I continue – absolutely! The sense of catharsis may have just been simply the result of over-oxygenation of course, but the surge of energy was wonderful. It was also a humbling experience to be a vessel for ideas and emotions far beyond my own abilities to articulate. I felt a great sense of connection, as though the past two centuries had simply evaporated and the man himself was still amongst us. I discovered patterns and connections which had not occurred to me when reading the material quietly and alone. I hope Shelley would have approved of what I had done to his poetry.

For me the work of Shelley is not an artifact to be studied and analyzed but a continuing personal inspiration for my political engagement. I am sure it will be the same for many more people when we release him from the sanitized, gilded cage in which the establishment has trapped him.

Let me tell you something Mark, Shelley, who went to his grave without seeing Mask of Anarchy published, would be overjoyed. Overjoyed because he wrote his poetry to inspire people to change the world the way you have been inspired. But I think his joy would be profoundly tinged with sadness, a sadness which stems from the realization that the world has not changed so very much from his times; the poor are still oppressed, and the rich have grown ever wealthier. Shame on us all.

Mark's article can be found here at his terrific website, New Leveller. It is reprinted with his permission. The banner image at the top of the post comes from Michael Demson's Masks of Anarchy, abrilliant graphic novel that can be purchased here.

Revolutionary Politics and the Poet. By Mark Summers

What I love about Mark Summers' writing is his ability to put Shelley in the context of his time, and then make what happened then feel relevant now. Both Mark and I sense the importance of recovering the past to making sense out of what is happening today. With madcap governments in England and the United States leading their respective countries toward the brink of authoritarianism, Shelley's revolutionary prescriptions are enjoying something of a renaissance; and so they should, we need Percy Bysshe Shelley right now!

One of the goals of my site is also to gather together people from all disciplines and walks of life who are interested in Shelley. One such person is Mark Summers. You have encountered his writing here before. One of Mark's stated goals is to "take Shelley to the streets". I have more to report about this later. There has been a long history of this, most recently during the Occupy Wall Street demonstrations. Mark is an e-Learning specialist for a UK Midlands based company and a musician specializing in experimental and free improvised forms. An active member of the Republic Campaign which aims to replace the UK monarchy with an accountable head of state, Mark blogs at at www.newleveller.net which focuses on issues of republicanism and radical politics/history. You can also find him on Twitter @NewLeveller. Mark's writing has a vitality and immediacy which is exhilarating. I first discovered him as a result an article of his which appeared in openDemocracy. I re-published here recently.

What I love about Mark Summers' writing is his ability to put Shelley in the context of his time, and then make what happened then feel relevant now. Both Mark and I sense the importance of recovering the past to making sense out of what is happening today. With madcap governments in England and the United States leading their respective countries toward the bring of authoritarianism, Shelley's revolutionary prescriptions are enjoying something of a renaissance; and so they should, we need Percy Bysshe Shelley right now!.

What comes next is Mark's follow-up to his important openDemocracy piece. Mark wrote his article in the summer of 2016; since then Donald Trump was elected President of the United States - making Mark's article prescient and even more compelling. Enjoy!

Revolutionary Politics and the Poet

"Ye are many, they are few!"

The anniversary of two events of primary importance in England's radical history occur in August; the birth of poet Percy Bysshe Shelley on the 4th (in 1792) and the Peterloo Massacre in Manchester, England on the 16th (in 1819). Last summer (27 July 2016) my thoughts Shelley’s great Poetical Essay on the State of Things was published on openDemocracy and it is a suitable moment to consider the relevance of another of his great works inspired by events in Manchester, the Mask of Anarchy (you can read it here). Like the openDemocracy article, this post is neither intended as a literary study of Shelley’s work nor an account of the origins of Shelley’s radical opinions. There are many people far better qualified for this task and I can only draw your attention to two examples, Paul Foot’s excellent article from 2006 or the materials on this fascinating blogsite by Graham Henderson. In both my openDemocracy article and the present post I have two aims. Firstly to outline my claim to Shelley as part of the tradition with which I identify and secondly to assess the importance of Shelley’s work and the invaluable lessons it has for us now.

Although popular pressure had been building for reform since the start of the French Revolution in 1789, economic depression and high unemployment following the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 intensified demands for change. In 1819 a crowd variously estimated at being between 60,000 and 100,000 had gathered in St Peters Field in Manchester to protest and demand greater representation in Parliament. The subsequent overreaction by Government militia forces in the shape of the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry led to a cavalry charge with sabres drawn. The exact numbers were never established but about 12 to 15 people were killed immediately and possibly 600-700 were injured, many seriously. For more information on the complex serious of events, go to this British Library resource and this campaign for a memorial. [Editor's note: For more on the Mask of Anarchy, follow this link to my review of Michael Demson's graphic novel, Masks of Anarchy]

Shelley was in Italy when news reached him of the events in Manchester and he set down his reaction in the poem Mask of Anarchy which contains the immortal lines contained in the title of my post. The work simmers over 93 stanzas with a barely controlled rage leading to a call to action and a belief that the approach of non-violent resistance (an approach followed by Gandhi over a century later) would allow the oppressed of England to seize the moral high ground and achieve victory. Such was the power of the poem that it did not appear in public until 1832, the year of the Great Reform Act which extended the voting franchise.

Detail from Michael Demson's Masks of Anarchy.

Anarchy – Chaos and Confusion as a Method of Control

An excellent place to start thinking about the relevance of the poem is with the eponymous evil villain, Anarchy. He leads a band of three tyrants which are identified as contemporary politicians, Murder (Foreign Secretary, Viscount Castlereagh), Fraud ( Lord Chancellor, Lord Eldon) and Hypocrisy (Home Secretary, Lord Sidmouth). But Shelley widens the cast of villains in his description to include the Church, Monarchy and Judiciary.

Last came Anarchy : he rode

On a white horse, splashed with blood ;

He was pale even to the lips,

Like Death in the Apocalypse.

And he wore a kingly crown ;

And in his grasp a sceptre shone ;

On his brow this mark I saw—

‘I AM GOD, AND KING, AND LAW!’

The promotion of anarchy with its attendant fear of chaos and disorder was one of the most serious accusations which could be levelled at authority. The avoidance of anarchy was also a concern of English radicals ever since the Civil War in the 1640s and Shelley was making the gravest personal attack with his explicit individual accusations. But Shelley’s attack is pertinent, the implicit threat of confusion and chaos to subdue a population for political ends is something which we experience today. The feeling of powerlessness which can result from an apparently confusing and chaotic situation is something which the documentary filmmaker Adam Curtis has termed ‘oh dearism’. In our own time he has identified recent Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne as deliberately using such a tactic. Likewise the Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn has been variously accused of being a threat to national security or a threat to the economy .

The 1819 Peterloo massacre occurred at a time of heightened external tension with fear that the French revolution would spread to Britain. The fear was not unfounded and various groups around the country emerged with such an intent, in many cases inspired by Tom Paine’s The Rights of Man which the Government had been trying to unsuccessfully suppress. The existence of an external threat combined with homegrown radicals was explicitly used as a reason for a policy of political repression and censorship. Likewise today an external threat, Islamic State combined with an entirely separate perceived internal threat (employee strike action) has been cited as justification for a whole range of measures including invasive communication monitoring (so called ‘Snoopers Charter’) without requisite democratic controls and a repressive Trade Union Bill seeking to shackle the ability of unions to garner support and carry out industrial action.

Detail from Michael Demson's Masks of Anarchy.

The Nature of Freedom

The nature of freedom is a problem which has bothered both libertarians and republicans for generations. In Mask of Anarchy where Shelley is enumerating the injustice suffered by the poor he clearly defines freedom in terms of the state of slavery, a core republican premise:

What is Freedom? Ye can tell

That which Slavery is too well,

For its very name has grown

To an echo of your own

The essence of freedom which has financial independence as a core component is clearly articulated over a number of stanzas, starting with:

‘’Tis to work and have such pay

As just keeps life from day to day

In your limbs, as in a cell

For the tyrants’ use to dwell,

‘So that ye for them are made

Loom, and plough, and sword, and spade,

With or without your own will bent

To their defence and nourishment.

In our own time freedom is frequently constrained by insufficient financial resources as a result of hardship caused by issues such as disability support cuts, chronic low wages and a zero-hours contract society. Shelley would have no problem with identifying Sports Direct owner Mike Ashley, playing with multi-million pounds football clubs while his workforce toil in iniquitous conditions for a pittance; or Sir Philip Green impoverishing British Home Stores pensioners to pile up a vast fortune for his wife in Monaco.

Disgustingly the only thing we need to update from Shelley's Mask of Anarchy is the cast of villains, the substance is unchanged!.

Non-Violent Resistance – A Way Forward

I pointed out that in the 1811 Poetical Essay, Shelley was searching for a peaceful way to elicit change in an oppressive hierarchical society. By 1819 Shelley has settled on his preferred solution of non-violent resistance.

Stand ye calm and resolute,

Like a forest close and mute,

With folded arms and looks which are

Weapons of unvanquished war,

‘And let Panic, who outspeeds

The career of armèd steeds

Pass, a disregarded shade

Through your phalanx undismayed.

Nonviolent resistance is not an instant solution and takes years of persistent and widespread enactment to be successful. A partial victory was secured in the 1830s with the Great Reform Act (1832) and the Abolition of Slavery Act (1834). But history has proved that it is a viable strategy, the independence of India being an eloquent testament.

Detail from Michael Demson's Masks of Anarchy.

This article is republished with the kind permission of the author. It appeared originally on Mark's superb blogsite (www.newleveller.net) on 7 August 2016.

The Political Fury of Percy Bysshe Shelley - by Mark Summers

The real Shelley was a political animal for whom politics were the dominating concern of his intellectual life. His political insights and prescriptions have resonance for our world as tyrants start to take center stage and theocracies dominate entire civilizations. Dismayingly, the problems we face are starkly and similar to those of his time, 200 years ago. For example: the concentration of wealth and power and the blurring of the lines between church and state. Some of you will have read my review of Michael Demson's history of Shelley's Mask of Anarchy. Guest contributor Mark Summers comment on the Mask says it all: "Disgustingly the only thing we need to update from Mask is the cast of villains, the substance is unchanged!." For Castlereagh read Rex Tillerson; for Eldon read Michael Flynn, for Sidmouth read Stephen Bannon and for Anarchy itself, we have, of course Trump:

Part of a new feature at www.grahamhenderson.ca is my "Throwback Thursdays". Going back to articles from the past that have new urgency, were favourites or perhaps overlooked. This article falls into the first category.

The real Percy Bysshe Shelley was a political animal for whom politics were the dominating concern of his intellectual life. His political insights and prescriptions have resonance for our world as tyrants start to take center stage, countries retreat into nationalism and theocracies dominate entire civilizations. Dismayingly, the problems we face are starkly similar to those of his time, 200 years ago. For example: the concentration of wealth and power and the blurring of the lines between church and state.

Some of you will have read my review of Michael Demson's history of Shelley's Mask of Anarchy. The reason poems like this are so important is that once upon a time the galvanized people to action. And they can again. People merely need to be inspired. As Demson demonstrates, The Mask of Anarchy is important because "unmasked" the true nature of the political order that was crushing England. Shelley's call for massive, non-violent protest was decades ahead of it's time and influenced unionorganizers and political leaders across the globe. But the more things change the more they seem to stay the same. Guest contributor Mark Summers comment on the Mask of Anarchy says it all: "Disgustingly the only thing we need to update from Mask is the cast of villains, the substance is unchanged!."

For Castlereagh read Rex Tillerson; for Eldon read Stephen Bannon, for Sidmouth read Michael Flynn and for Anarchy itself, Trump:

I met Murder on the way--

He had a mask like Castlereagh--

Very smooth he looked, yet grim;

Seven blood-hounds followed him:

All were fat; and well they might

Be in admirable plight,

For one by one, and two by two,

He tossed them human hearts to chew

Which from his wide cloak he drew.

Next came Fraud, and he had on,

Like Eldon, an ermined gown;

His big tears, for he wept well,

Turned to mill-stones as they fell.

And the little children, who

Round his feet played to and fro,

Thinking every tear a gem,

Had their brains knocked out by them.

Clothed with the Bible, as with light,

And the shadows of the night,

Like Sidmouth, next, Hypocrisy

On a crocodile rode by.

And many more Destructions played

In this ghastly masquerade,

All disguised, even to the eyes,

Like Bishops, lawyers, peers, or spies.

Last came Anarchy: he rode

On a white horse, splashed with blood;

He was pale even to the lips,

Like Death in the Apocalypse.

And he wore a kingly crown;

And in his grasp a sceptre shone;

On his brow this mark I saw--

'I AM GOD, AND KING, AND LAW!'

To someone today concerned with issues such as social and political equality, Shelley therefore offers two things; firstly a shocking wake up call to the fact things have changed so little, and secondly a storehouse of remarkably sophisticated ideas about what to do about this.

One of the goals of my site is also to gather together people from all disciplines and walks of life who are interested in Shelley. One such person is Mark Summers. One of his stated goals is to "take Shelley to the streets". I hope to have more to report about this later. There has been a long history of this, most recently during the Occupy Wall Street demonstrations. Mark is an e-Learning specialist for a UK Midlands based company and a musician specializing in experimental and free improvised forms. An active member of the Republic Campaign which aims to replace the UK monarchy with an accountable head of state, Mark blogs at at www.newleveller.net which focuses on issues of republicanism and radical politics/history. You can also find him on Twitter @NewLeveller. Mark's writing has a vitality and immediacy which is exhilarating. I first discovered him as a result of the article I am republishing below. It was written for openDemocracy. Mark has gone on to write more about Shelley. I hope this is only the beginning.

On his blog, Mark notes that:

"I take inspiration from the radical and visionary Leveller movement which flourished predominantly between the English Civil Wars of the mid 17th Century. In a series of brilliant leaflets and pamphlets the Levellers articulated their commitment to civil rights and a tolerant social settlement. I consider the ideals of justice and accountability expressed by this movement to be of continuing importance and their proposed solutions provide valuable lessons for meeting contemporary challenges. Clearly the 21st Century is vastly different to the 17th and it is my aim to apply the spirit of Leveller thinking rather than a simple reiteration of their demands. As such I espouse the aims of Civic Republicanism, church disestablishment along with the pursuit of social equality and inclusion."

To that, I say hear, hear! Now, allow me to introduce you to his fast paced prose which betrays great admiration and affection for the work and life of Percy Bysshe Shelley.

The Political Fury of Percy Bysshe Shelley

Imagine discovering a new set of string quartets by Beethoven or a large canvas by Turner that was thought to be lost. In either case, the mainstream media would have been agog, just as they were for the discovery of an original Shakespeare folio in April 2016.

So it’s remarkable that the release to public view of a major work by a near contemporary of both these artists on November 10 2015—the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley—was met with an air of such disinterest (The Guardian newspaper excepted).

There were brief mentions and some excerpts were read out on BBC Radio 4, but no welcoming comments appeared from government ministers including the UK’s Minister for Culture, Media and Sport. So much for a significant early piece by one of Britain’s most revered poets.

The work in question was a pamphlet by Shelley entitled the “Poetical Essay on the Existing State of Things,” written anonymously in 1811 in support of Irish journalist Peter Finnerty who was imprisoned for libel after criticising the British military command during the Napoleonic Wars. Although a thousand copies of the pamphlet were printed, it is not known how successful the poem turned out to be in terms of raising money; what’s clear is that the work disappeared from view.

During the 1870s, some expert detective work positively identified a surviving example of the poem as the work of Shelley. Much more recently in 2006, a single copy was re-discovered by the scholar H.R.Woudhuysen, but it was lodged in a private collection so the work remained hidden from public view.

That was the position until 2015, when this private copy was acquired by the Bodleian Library in Oxford. You can now read (and even download) a copy from the Bodleian Library website. Poet and ex-children’s Laureate Michael Rosen had been campaigning for the release of the work for some time previously. In a blog post he gave his thoughts about why, in his words, the poem had been ‘suppressed,’ and why he had campaigned to get it released to the public.

Rosen argues that confusing the artistic substance of the pamphlet with the ownership of the physical artifact had meant that only a few privileged people could access the full content—a scandalous situation in his view.

What about the pamphlet itself? The Poetical Essay consists of a prose introduction along with a 172 line poem followed by accompanying notes. The nature of the work is clear: it’s a reasoned and passionate response to the perceived ills and injustices of the world by an 18 year old radical.

First and foremost the young Shelley issues a pointed condemnation of the militaristic stance of the British establishment, along with stanzas that are vehemently anti-monarchist and implacably opposed to the abuses of wealth that were prevalent at the time:

“Man must assert his native rights, must say;

We take from Monarchs’ hand the granted sway;”

The range and scope of his criticism is impressive, including a keen censure of the role of the media. Going way beyond simple anti-monarchism, the introduction to the poem reveals a subtle understanding of the kind of secular republican society that Shelley desires. For example, he states that:

“This reform must not be the work of immature assertions of that liberty, which, as affairs now stand, no one can claim without attaining over others an undue, invidious superiority, benefiting in consequence self instead of society.”

In this passage he correctly identifies the problem of equating liberty with an unrestrained personal freedom—what the philosopher Isaiah Berlin labeled as “positive liberty” in the 1950s. This remains a central concern of republicanism today. Likewise he warns clearly about the dangers of violent revolution in advancing the cause of egalitarianism:

“…it must not be the partial warfare of physical strength, which would induce the very evils which the tendency of the following Essay is calculated to eradicate; but gradual, yet decided intellectual exertions must diffuse light, as human eyes are rendered capable of bearing it.”

Interestingly, Shelley uses the words “patriot” and “patriotism” three times in the body of the poem. On each occasion he makes it clear that the duty of a patriot is to attempt to shine a light on the corruption and secrecy that surrounds autocratic government. For example:

“And shall no patriot tear the veil away

Which hides these vices from the face of day?”

But this range of criticism is, ironically, also a source of weakness in the work. As John Mullen pointed out in The Guardian, Shelley’s targets are hidden behind abstractions. The poem doesn’t deliver the punch of some of his later works such as the sonnet “England in 1819”, and the poem “Masque of Anarchy,” where the focus is on a single event—the outrage of the 1819 Peterloo Massacre. Interestingly, both of these works were also suppressed until the 1830s.

Was the public’s 200 year long wait for the poem worthwhile? For me the answer is ‘yes’, once I had become accustomed to the language and phrasing that Shelley uses. As Rosen says in this article by Alison Flood:

“…the poem was full of ‘portable triggers, lines of political outrage for people to catch and hold’. He added: ‘Political writing is often like that, but in times of oppression and struggle, this is no bad thing: a portable phrase to carry with us may help.’”

Ultimately, the concealment of Shelley’s Poetical Essay highlights a number of important contemporary issues about the values of our own society, including the rights of possession and access to important cultural artifacts.

Undoubtedly, the pamphlet contains explosive ideas which the British establishment might continue to regard as dangerous. It would be crass and superficial not to acknowledge that the situation in which Shelley found himself in 1811 is very different from the one we inhabit in the second decade of the 21st Century. Yet in some respects the poet would be depressed to see how certain aspects of social and political life have barely changed.

First, the poem was written to help raise money for a journalist—Finnerty—who was critical of Britain’s military commanders and who was imprisoned for libel as a result. With the increasing focus on military issues in Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria and elsewhere can we be sure that important criticisms of the military are not being similarly gagged today? Note how the failures of the British Army in Helmand Province, Afghanistan, for example, have been suppressed, including those highlighted by servicemen who were directly involved. News continues to be managed and the opinions of pacifist ex-servicemen are still marginalised.

Second, a central concern of Shelley and other critics in 1811 was the way in which the poor were made to bear the costs of military activity, while the glory and spoils of war were garnered by the establishment. What would his poem say if it were to be written today about the commitment of the UK government to spend two per cent of GDP on the military, or to give tax cuts to the wealthy, or to protect trusts and tax havens while cutting disability benefits, some of which affect ex-servicemen?

Finally, Shelley’s concern with the methods by which society can be moved from a position where privilege holds power to one where power is distributed throughout society and held accountable is just as real today. But here he runs into the same problems as everyone else who is seeking radical change.

Shelley claimed that the actions he was proposing in his pamphlet did not infringe on the interests of Government, but this was surely naive. Taking power from those who possess it is itself a revolutionary act. He needed to have looked no further than recent history (for him) in the form of the American Revolution for confirmation of this fact.

As Shelley put it in his poem:

“Then will oppression’s iron influence show; The great man’s comfort as the poor man’s woe.”

How to achieve peaceful and lasting change in modern societies remains an unanswered question, and one that’s ripe for fresh action and inspiration. Dangerous ideas from poets are just what a genuinely open society should be able to encompass and discuss, not conceal, ignore or suppress.

This article originally appeared on 27 July 2016 and can be found here. It is reprinted with the permission of the author and openDemocracy. My thanks to both.

- Mary Shelley

- Frankenstein

- Mask of Anarchy

- Peterloo

- Anna Mercer

- Michael Demson

- William Godwin

- Coleridge

- An Address to the Irish People

- Byron

- Richard Carlile

- Jonathan Kerr

- Pauline Newman

- Mutability

- Epipsychidion

- Thomas Paine

- Mont Blanc

- Mark Summers

- Paul Foot

- George Bernard Shaw

- Chartism

- Diodati

- Timothy Webb

- Mary Wollstonecraft

- Defence of Poetry

- William Wordsworth

- Queen Mab

- free media

- Daniel O'Connell

- Vindication of the Rights of Women

- Ginevra

- Jacqueline Mulhallen

- Edward Dowden

- Robert Southey

- Chamonix

- James Connolly

- Edward Aveling

- Claire Clairmont

- Levellers

- England in 1819

- Lynn Shepherd

- To Autumn

- Alastor

- Ozymandias

- Francis Burdett

- Kenneth Neill Cameron

- Thomas Kinsella

- Tess Martin

- Geneva

- Proposal for an Association

- Cenci

- Kathleen Raine

- Richard Emmet

- Martin Bodmer

- Sonia Liebknecht

- Radicalism

- Keats-Shelley Association

- Trotsky

- Isabel Quigley

- Alien

- Michael Gamer

- Maria Gisborne

- World Socialism Web Site

- Theobald Wolfe Tone

- Butcher's Dozen

- Percy Shelley

- Freidrich Engels

- Milton

- Blade Runner

- ararchism

- Paul Bond

- Rosa Luxemburg

- Masks of Anarchy

- Keats-Shelley Review

- John Keats

- Leigh Hunt

- A Defense of Poetry

- Humphry Davy

- perfectibility

- Henry Hunt

- Paradise Lost

- Political Justice

- Shelley Society

- Polidori

- Necessity of Atheism

- David Carr

- The Last Man

- Harriet Shelley

- Eleanor Marx

- Industrial Workers of the World

- A Philosophical View of Reform

- Joe Hill

- The Easter Rising

- When the Lamp is Shattered

- Richard Margraff Turley

- Henry Salt

- Buxton Forman

- Lord Sidmouth

- Valperga

- Daisy Hay