The Politics of Percy Bysshe Shelley

Shelley is a poet and thinker whose ideas have uncanny application to the modern era. His atheism, humanism, socialism, feminism, vegetarianism all resonate today. His critiques of the tyranny and religious oppression of the early 19th century seem eerily applicable to the early 21st century. He is the man who first conceived the concept of massive, non-violent protest as the most appropriate and effective response to authoritarian oppression. I have written about this in Shelley in our Time and What Should We Do to Resist Trump? But it may come as a surprise to many to learn Shelley also turned his mind to issues such as economics and the English national debt.

Today, the British government frames the argument around national debt by referring to the need for ‘us’ to make sacrifices or the fact that ‘we’ have been living beyond ‘our’ means and need austerity to survive economically. Despite evidence to the contrary, this ideology resonates with many people who think that in some way, we are all responsible for the financial crisis. We live within this widespread, false ideology, and some of us fight against it. However, a look back to the nineteenth century reveals that this fight was already taking place, and that capitalism was employing many of the tricks it still uses today. Jacqueline Mulhallen looks at the political life of the radical romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley in her new biography and reveals that there was much more to him than first meets the eye.

Shelley is a poet and thinker whose ideas have uncanny application to the modern era. His atheism, humanism, socialism, feminism, vegetarianism all resonate today. His critiques of the tyranny and religious oppression of the early 19th century seem eerily applicable to the early 21st century. He is the man who first conceived the concept of massive, non-violent protest as the most appropriate and effective response to authoritarian oppression. I have written about this in Shelley in our Time and What Should We Do to Resist Trump? But it may come as a surprise to many to learn Shelley also turned his mind to issues such as economics and the English national debt. For example:

"I forbear to address you as I had designed on the subject of your income as a public creditor of the English Government as it seems you have not the exclusive management of your funds...In vindication of what I have already said allow me to turn your attention to England at this hour. [There follows a detailed examination of the national debt and the unstable political situation in England] The existing government, atrocious as it is, is the surest party to which a creditor can attach himself - he may reason that "it may last my time" - though in the event, the ruin is more complete than in the case of popular revolution."

- Shelley to John and Maria Gisborne, Florence, 6 November 1819

This quote is drawn from a series of letters from Shelley to his friends John and Maria Gisborne. Shelley is discussing the fact that John had invested his money in "British Funds". These were a sort of "savings bond" used to finance England's staggering national debt. By 1815 the national debt had risen to over a billion pounds -- more than 200% of the GDP. Compare this to the modern era:

To the end of his life, Shelley continually pestered John to remove his money from the Funds - he expected ruin for his friend. Shelley's letters demonstrate that his genius extended far beyond poetry and philosophy. The letter also contains the first reference to A Philosophical View of Reform, which Shelley wrote between November 1819 and May 1820: he notes that he had "deserted the odorous gardens of literature to journey across the great sandy desert of Politics." And what an epic journey it turned out to be.

This letter shows a side of Shelley that few have ever seen. and today's guest article by Jacqueline Mulhallen brings this side into sharp focus. The article appeared on the website of Pluto Press, publisher of Jacqueline's book, Percy Bysshe Shelley: Poet and Revolutionary. You can find it here. And you can read my own review here. Without further ado, here is the article.

A Philosophical View of Reform: The Politics of Percy Bysshe Shelley

by Jacqueline Mulhallen

Today, the British government frames the argument around national debt by referring to the need for ‘us’ to make sacrifices or the fact that ‘we’ have been living beyond ‘our’ means and need austerity to survive economically. Despite evidence to the contrary, this ideology resonates with many people who think that in some way, we are all responsible for the financial crisis. We live within this widespread, false ideology, and some of us fight against it. However, a look back to the nineteenth century reveals that this fight was already taking place, and that capitalism was employing many of the tricks it still uses today. Jacqueline Mulhallen looks at the political life of the radical romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley in her new biography and reveals that there was much more to him than first meets the eye.

- Introduction from Pluto Press

Debt in the Time of Shelley

Shelley's drawing affixed to his copy of A Philosophical View of Reform. It demonstrates a quite extraordinary gift for draughtsmanship.

‘In 1819, Percy Shelley was writing A Philosophical View of Reform. In its pages, he is clear about whom he considered responsible for the national debt, which at that time was bigger than it had ever been before – in 1815 the interest amounted to £37,500,000. Shelley, like many people today, fought against the common consensus and blamed the bankers and the nation’s financial institutions. He clearly expressed his contempt in them; the ‘stock jobbers, usurers, directors, government pensions, country bankers: a set of pelting wretches who think of any commerce with their species as a means not an end’ and whose position in society he believed was based on fraud. Shelly himself surprisingly came from the landed aristocracy, however he had no love for this class either, as their existence was built upon force and was what he labelled ‘a prodigious anomaly’. He also talked of the rise of the newly wealthy as a different form of aristocracy who created a double burden on those whose labour created ‘the whole materials of life’. He could see that they together formed one class – ‘the rich’.

It was obvious to Shelley that the national debt had been contracted by ‘the whole mass of the privileged classes towards one particular portion of those classes’ – just as is the case today. ‘If the principal of this debt were paid … it would be the rich who alone could, as justly they ought, to pay it … As it is, the interest is chiefly paid by those who had no hand in the borrowing and who are sufferers in other respects from the consequences of those transactions in which the money was spent’.

Austerity and War in the Nineteenth Century

A Page from A Philosophical View of Reform.

Shelley also expressed what he saw as a clear connection between austerity and war. The national debt was ‘chiefly contracted in two liberticide wars’, against the American revolutionaries and then the French revolutionaries. The money borrowed could have been spent in making the lives of working people better. As it was, the majority of the people in England were observed by Shelley as ‘ill-clothed, ill-fed, ill-educated’. After the Napoleonic Wars unemployment soared and returning soldiers were often found begging in the streets. The condition of all the classes ‘excepting those within the privileged pale’ was ‘singularly unprosperous’, allowing Shelley to comment, ‘The power which has increased is the power of the rich’.

Shelley also believed that anyone whose ‘personal exertions’ were ‘more valuable to him than his capital’ such as surgeons, mechanics, farmers and literary men (people often described as middle class) were only ‘one degree removed from the class which subsists by daily labour’ and therefore should not be classed with the rich. However, Shelley returned again and again to his obsession, the situation of the worker. His essay A Philosophical View of Reform, which on the surface was about the possibilities of reforming the English parliament to make it more representative, contained within it a message about how reform would not be enough. Why demand universal suffrage, he asks, when you can demand a Republic: ‘the abolition of, for instance, monarchy and aristocracy, and the levelling of inordinate wealth, and an agrarian distribution, including the parks and chases of the rich?’

The Radical Questions of the Day

As a boy, Shelley was probably involved in anti-slavery activity in his home town of Horsham in Sussex. His father had been elected to Parliament as an MP to support the anti-slave trade bill in 1790, although some corrupt practices meant that he lost his seat before he was able to vote on the question. But in 1807, the year the slave trade was abolished, the inhabitants of Horsham were particularly active, with a close family friend of the Shelleys standing on an anti-slavery platform.

Shelley also supported the independence of Ireland, arguing that the repeal of the Act of Union with England was a more important issue than Catholic Emancipation (although he supported the campaign for Catholics to sit in the British Parliament). Shelley admired Thomas Paine, the author of The Rights of Man and Mary Wollstonecraft, the author of A Vindication of the Rights of Women. He went so far as to try to renounce his inheritance as a member of the wealthy landowning class in favour of his sisters, though he only succeeded in transferring some of this wealth to his brother. He supported women writers including his own wife, Mary Shelley, the daughter of Mary Wollstonecraft and author of Frankenstein.

Percy Shelley believed that equality was the natural state. He was ahead of his time. And yet, in the twenty-first century we still labour in an unequal, class society, and we still live with racism, exploitation and sexism. As is well known, the gap between the rich and the poor has widened to become greater than at any time in the last fifty years.

Legacy

Despite living 200 years ago, Shelley’s legacy is very much with us today, even if it was ignored and ridiculed in his lifetime. He attempted to get A Philosophical View of Reform published in England, but the publisher he submitted the manuscript to ignored him. Not having other contacts in England, Shelley left the essay unfinished. It was not published until 100 years after his death and so was never read by his contemporaries, although he recycled parts of it into his Defence of Poetry. Even nowadays it is not often read or discussed, and it deserves to be better known. Shelley should be honoured as a political thinker, as well as a magnificent poet. In A Defence of Poetry, Shelley describes poets as the ‘unacknowledged legislators of the world’ and his example shows the way in which poets can be closely involved with the political issues of the day.

Jacqueline Mulhallen wrote and performed in the plays Sylvia and Rebels and Friends. She is the author of The Theatre of Shelley (Open Book Publishers, 2010) and contributed a chapter on Shelley to The Oxford Handbook to Georgian Theatre (OUP, 2014), which was shortlisted for the Theatre Book Prize 2015.

Percy Bysshe Shelley: Poet and Revolutionary is available to buy from Pluto Press. The foregoing article is reproduced with their kind permission. Visit Jacqueline's website here.

Keats’s Ode To Autumn Warns About Mass Surveillance

John Keats’s ode To Autumn is one of the best-loved poems in the English language. Composed during a walk to St Giles’s Hill, Winchester, on September 19 1819, it depicts an apparently idyllic scene of harvest home, where drowsy, contented reapers “spare the next swath” beneath the “maturing sun”. The atmosphere of calm finality and mellow ease has comforted generations of readers, and To Autumn is often anthologised as a poem of acceptance of death. But, until now, we may have been missing one of its most pressing themes: surveillance.

Introduction.

In his wonderful graphic novel, Masks of Anarchy (reviewed by me here) Professor Michael Demson offers a glimpse into the sort of surveillance ("spying") to which Shelley was subjected. His letters were read, he was followed, he was the subject of specific investigatiuons authorized by Lord Sidmouth, the Home Secretary who presided of England's massive spying apparatus. Sidmouth was an arch-conservative figure in the Georgian period. According to the Encyclopedia Britannica:

As home secretary in the ministry of the earl of Liverpool, from June 1812 to January 1822, Sidmouth faced general edginess caused by high prices, business failures, and widespread unemployment. To crush demonstrations both by manufacturers and by Luddites (anti-industrial machine-smashing radicals) he increased the summary powers of magistrates. At his insistence the Habeas Corpus Act was suspended in 1817, and he introduced four of the coercive Six Acts of 1819, which, among other provisions, limited the rights of the people to hold public meetings and to circulate political literature.

These measures are among the most draconian anti-democratic measures ever enacted by an English government. It is easy to see why Shelley fell afoul of the authorities. From a very young age he was constantly and openly rebelling against the government and social conventions of the day. Much of his prose and poetry explicitly reacts to actions taken by Lord Sidmouth and in fact Lord Sidmouth is one of the three named agents of Anarchy in the Mask of Anarchy:

Clothed with the Bible, as with light, / And the shadows of the night, / Like Sidmouth, next, Hypocrisy / On a crocodile rode by. And many more Destructions played / In this ghastly masquerade, / All disguised, even to the eyes, / Like Bishops, lawyers, peers, or spies.

Shelley learning of Peterloo. Imagined by Michael Demson in Masks of Anarchy. Buy it here.

Note the specific reference to spies here. This now famous poem, which had enormous political influence over succeeding generations, was never published in his life time - directly as a consequence of laws enacted by Lord Sidmouth. PMS Dawson and Kenneth Neill Cameron (among others) offer penetrating insights into the effect this had on Shelley. He came to the attention of the authorities very early thanks to his visit to Ireland in 1812 (when he was 20) to support the cause of separation and the repeal of the Act of Union. A trunk of his, containing letters and copies of his Address to the Irish People, was detained at the border and forwarded to the Home office where its contents were inspected by Lord Sidmouth who personally authorized the surveillance of Shelley. Shelley never once stopped publishing (or attempting to publish) excoriating critiques of the government. For example: Letter in Defence of Richard Carlile, A Proposal for Putting Reform to the Vote, An Address to the People on the Death of the Princess Charlotte and A Philosophical View of Reform.

The effect of the government's attention however made Shelley fearful and at times even (justifiably) paranoid. It is surely one of the principle reasons he went into a self-imposed exile in Italy. If we do not understand just how pervasive and intrusive government surveillance was during this period, we cannot understand the poets and essayists of the time.

Richard Marggraf Turley (see below) has now offered a tantalizing, penetrating and brilliantly written insight into the effect of Lord Sidmouth's repressive laws on another famous poet of the period: John Keats. Keats reacted to the government's mass surveillance in a very different way, and I will turn it over now to Richard to tell the story.

Keats’s Ode To Autumn Warns About Mass Surveillance and Social Sharing.

by Richard Marggraf Turley

Richard Marggraf Turley. Photo: Sara Penrhyn Jones

John Keats’s ode To Autumn is one of the best-loved poems in the English language. Composed during a walk to St Giles’s Hill, Winchester, on September 19 1819, it depicts an apparently idyllic scene of harvest home, where drowsy, contented reapers “spare the next swath” beneath the “maturing sun”.

The atmosphere of calm finality and mellow ease has comforted generations of readers, and To Autumn is often anthologised as a poem of acceptance of death. But, until now, we may have been missing one of its most pressing themes: surveillance.

The opening of the second stanza appears to be a straightforward allusion to personified autumn: “Who hath not seen thee oft amid thy store?” But that negative is odd, and hints at a more troubling side to the famous poem. Keats, a London boy, was walking in Winchester’s rural environs to get away from it all – but rather than describing a peaceful stroll, the poem seems to form an anxious meditation on the impossibility of privacy.

St Giles’s Hill, Winchester, in 2010. Peter Trimming/Geograph.org, CC BY-SA

Seen thee

We might assume mass surveillance is a modern phenomenon, but “surveillance” is a Romantic word, first introduced to English readers in 1799. It acquired a chilling sub-entry in 1816 in Charles James’s Military Dictionary: the condition of “existing under the eye of the police”.

But why would Keats have been thinking about spies in the St Giles cornfield? Rewind six days to September 13, 1819, when Henry “Orator” Hunt was entering London to stand trial for treason.

The political reformer had been arrested in Manchester for speaking at the Peterloo Massacre. Hunt was welcomed to the capital by a crowd of 300,000, with Keats, whose literary circle included political radicals, among those lining the streets to catch a glimpse of the government’s greatest bugbear.

London was on lock down. The Bank of England had closed its doors, the entrance to Mansion House was packed with constables and the artillery was on standby. Spies mingled with the Orator’s supporters, listening out for murmurs of popular uprising.

These were dangerous times, which To Autumn perhaps acknowledges with its opening allusion to close conspiracy and loading (weapons): Close bosom-friend of the maturing sun / Conspiring with him how to load and bless / With fruit …

Usually a garrulous letter writer, Keats waited until September 18 – the day before he wrote his ode – to describe Hunt’s procession to his brother and sister-in-law, and then in only the sketchiest terms. He notes the huge numbers but carefully distances himself from the cheering crowds, claiming it had taken him all day to feel “among men”.

Keats is uncharacteristically circumspect, almost as if he feared his correspondence might be intercepted – and perhaps for good reason.

Keats posted two letters during Hunt’s pageant, to his fiancé Fanny Brawne, and to his friend Charles Brown. The first letter arrived without mishap, but Brown’s went missing for 11 days. Later, Keats told him he believed the letter “had been stopped from curiosity” – that is, read by third parties.

The Massacre of Peterloo. George Cruikshank/Wikimedia

The truth was more mundane: Keats had got Brown’s address wrong, and the missive duly turned up on September 24. The letter has since been lost, and we can only guess at its contents, but it’s not inconceivable that, in the midst of Hunt’s maelstrom, Keats had been more candid about his support for the “hero of Peterloo”.

What we do know is that when Keats was writing his great ode on September 19, he suspected his private correspondence, posted during one of the most controversial political marches of the age, was in the hands of government spies.

Spies and informers

Keats’s creative antennae were already attuned to the issue of surveillance before this incident. His long poem Lamia, finished that same September, describes its heroine being tracked through the streets of Corinth by “most curious” spies (compare the phrase Keats used to refer to his missing letter: “stopped from curiosity”). That poem opens with a queasy scene in which Hermes transforms Lamia from serpent to woman. The price is information: Lamia agrees to give up the location of a nymph’s “secret bed” to the priapic god.

A rosy-hued Winchester cornfield might seem a long way from buzzing Corinth, or the violent scenes at Peterloo, or indeed the convulsed capital itself. But the field’s apparent calm is actually a fault line in Keats’s supposedly idyllic poem: the reapers, whose hooks lie idle, ought to be working flat out.

Landowners often grumbled about the laziness of Hampshire’s (poorly paid) casual labourers. It could be that Keats’s ode unwittingly drops the delinquent reapers in it, the poem’s lens giving them away at their “secret bed” (to recall Lamia’s betrayal of the sleeping nymph).

To Autumn is full of directed acts of invigilation: looking (patiently), watching (hours by hours), and seeking abroad (Keats’s first draft was more ominous: “whoever seeks for thee”). All the while those poor labourers were oblivious to the fact that their furtive nap was being observed, and carefully recorded.

Because let’s not forget, Keats is describing actual workers, real people whose slacking off he reports as unthinkingly as we might share our own peers’ political views or locations on social media. As casually as a Google car might capture a moonlighting worker up a ladder outside someone’s house.

When we take all this into account, To Autumn begins to read as an all-seeing optic, internalising the very surveillance culture Keats worried about, and itself becoming a spy transcript.

The ode is an early example of how art and literature process the psychological impacts of intrusive supervision. Written (in Keats’s mind) under surveillance, and bearing the marks of that imaginative pressure, the poem offers itself as a powerful document of what happens to communities, to social groups – to sociability itself – when watching, informing and being informed on become the norms of human interaction.

Richard Marggraf Turley is an award-winning Welsh writer and critic, author of Wan-Hu's Flying Chair and The Cunning House, as well as books on the Romantic poets. He was born in the Forest of Dean and lives in West Wales, where he teaches English Literature and Creative Writing at Aberystwyth University. He is the University’s Professor of Engagement with the Public Imagination. You can find him on Twitter and here on the web. This article was originally published by The Conversation and you can read it here. It is republished here under a Creative Commons Licence and with the permission of the author. Thank you, Richard.

Shelley Lives - Taking the Revolutionary Poet Shelley to the Streets.

Last fall Mark Summers did something absolutely fantastic: HE ACTUALLY TOOK SHELLEY'S POETRY TO A STREET PROTEST. Read his moving account of his experience. There are lessons for all of us in his experience. I think Mark's article is one of the most important I have published - and every student or teacher of Shelley needs to pay close attention to what Mark did. The revolutionary Shelley would be ecstatic!

One of the goals of my site is also to gather together people from all disciplines and walks of life who are interested in Shelley. One such person is Mark Summers. You have encountered his writing on my site: The Political Fury of Percy Bysshe Shelley and Revolutionary Politics and the Poet. Mark Summers came late to Shelley - he first encountered him when the newly discovered Poetical Essay on the Existing State of Things was published for the first time in late 2015. But he was a quick learner, and I think he has a better sense of Shelley than many people who have been studying him for thirty years.

Mark is an e-Learning specialist for a UK Midlands based company and a musician specializing in experimental and free improvised forms. An active member of the Republic Campaign which aims to replace the UK monarchy with an accountable head of state, Mark blogs at at www.newleveller.net which focuses on issues of republicanism and radical politics and history. You can also find him on Twitter @NewLeveller.

Mark's writing has a vitality and immediacy which is exhilarating. What I love most about it is his ability to put Shelley in the context of his time, and then make what happened then feel relevant now. Both Mark and I sense the importance of recovering the past to making sense out of what is happening today. With madcap governments in England and the United States leading their respective countries toward the bring of authoritarianism, Shelley's revolutionary prescriptions are enjoying something of a renaissance; and so they should, we need Percy Bysshe Shelley right now!

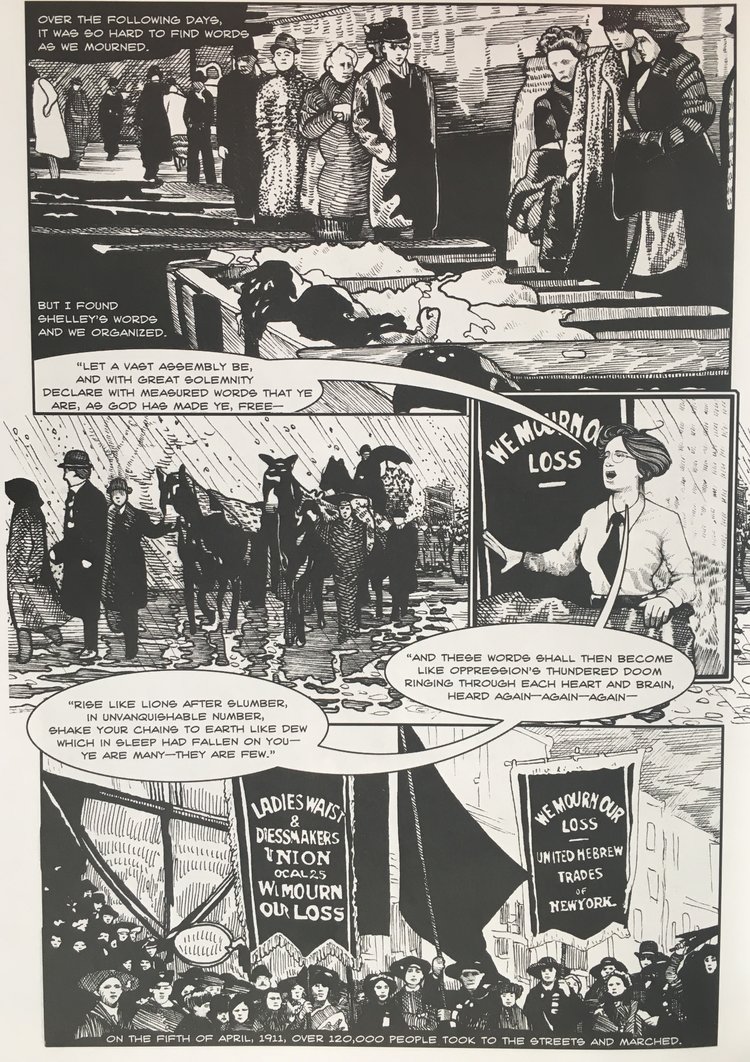

One of Mark's dreams was to "take Shelley to the streets". There has been a long history of this, most recently during the Occupy Wall Street demonstrations. Then there was the early 20th Century union organizer Pauline Newman who deployed Shelley's poetry to great effect while founding the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union. I wrote about that in Masks of Anarchy by Michael Demson. I also recently reported on a highly unusual but effective use of Shelley's The Mask of Anarchy by English fashion designer John Alexander Skelton: Shelley Storms the Fashion World With Mask of Anarchy.

Well, last fall Mark Summers did something absolutely fantastic: HE ACTUALLY TOOK SHELLEY'S POETRY TO A STREET PROTEST. What follows is his moving account of his experience. There are lessons for all of us in his experience - including some very practical ones such as the correct use of a megaphone! I think Mark's article is one of the most important I have published - and every student or teacher of Shelley needs to pay close attention to what Mark did. It is easy for us to chat amiably about Shelley in seminar rooms or at conferences, to comment on our FaceBook pages or Twitter accounts - it is entirely another thing altogether to go to a protest and read Shelley aloud to demonstrators. Yet this is EXACTLY how I think Shelley would have wanted his poetry to be heard. The closest I have come to Mark's experience pales in comparison: I have taken to working Shelley into all my speeches. And what I have taken away from the experience is very similar to what Mark learned. So grab a coffee or a whiskey (or both) and settle in for a terrific read.

Suits, Poetry and Megaphones; My Experience with Shelley at #TakeBackBrum 2016 - by Mark Summers

In previous posts and articles I have described some of the ways in which the works of the great philosopher and poet Percy Bysshe Shelley have stood the test of time. My central point is that beneath the establishment whitewash, Shelley’s work is as relevant to radical politics now as it was two centuries ago; his concerns are our concerns. So it has been an idea of mine to take Shelley back to where he belongs – the streets of Britain, via a megaphone!

Protest and Poetry

This year the Conservative Party held its annual conference in central Birmingham between the 2nd and 5th October. As a means of protesting the Government’s austerity measures which has seen the poorer and more vulnerable members of society paying for the excess and incompetence of a broken financial system, the People’s Assembly organized a weekend of protest in the city. With our presence at the start of the Sunday protest march, the Birmingham branch of Republic Campaign drew attention to the fact that monarchy is one of the few institutions completely shielded from the cuts inflicted on the rest of society. This presented the perfect opportunity to debut my ‘Street Shelley’ plan especially as between 10,000 and 20,000 people would be queuing up to march past.

Deciding that road transport and parking would be a nightmare I took the train into Birmingham. It was an almost surreal experience as protestors laden with banners, flags and leaflets rubbed shoulders (literally in the case of a crowded train) with conference delegates in suits and carefully coiffured hair!. I had chosen my poems beforehand, England in 1819, Masque of Anarchy and Poetical Essay on the Existing State of Things. Three of the most radical and hard hitting of Shelley’s pieces. The major problem I needed to overcome was a total lack of experience of poetry recitation! My original plan had been to include some stanzas from the great chartist poets such as Gerald Massey.

Gerald Massey, Chartist, mid 1850's. From Samuel Smiles' Brief Biographies, 1876.

But powerful as these works are (I must get around to writing about them very soon) they proved far trickier for a novice to handle than the fluid lines of Shelley. Considering the fact that I was also using a megaphone in a restless crowd I decided to play safe by letting the words of the poems do the work.

Learning Quickly

As a shorter sonnet, England in 1819 was suitable for reading in its entirety. But the longer poems needed more careful consideration. One of the delights of reading both Mask of Anarchy and Poetical Essay at your leisure is the way in which Shelley structures his material, diverting now this way, now that way to provide background and develop his theme. This would simply not work for a shifting crowd where the aim is for impact in an environment with competing demands for attention. The best plan would be to choose portions in the hope of hooking people in to discover more. Selecting the material from Mask of Anarchy was a relatively straightforward task with Shelley deftly creating distinct points of tension within its tripartite structure. This means that groups of 10 or 12 stanzas are distributed through the poem which have both internal coherence and impact. So, for example, the following section works as a unit, especially as it contains one the most famous lines in radical poetry "Ye are many—they are few."

Men of England, heirs of Glory,

Heroes of unwritten story,

Nurslings of one mighty Mother,

Hopes of her, and one another ;

Rise like Lions after slumber

In unvanquishable number.

Shake your chains to earth like dew

Which in sleep had fallen on you—

Ye are many—they are few.

…….

[Through to]

……

Paper coin—that forgery

Of the title-deeds, which ye

Hold to something from the worth

Of the inheritance of Earth.

’Tis to be a slave in soul

And to hold no strong control

Over your own wills, but be

All that others make of ye.

Reciting the poetry was an experience with very steep vertical learning curve. For example, I quickly discovered that it was more effective to actually turn down the megaphone volume and raise the volume of my voice. In this way I realized just how well it works as a visceral language with a weight capable of projection. Lines such as

’Tis to see your children weak

With their mothers pine and peak,

could be delivered with energy and passion, the whole thing becoming quite a cathartic experience. Strangely, despite having spent much time over the past few months with these works I discovered that the meaning of a few words and lines were less obvious than I originally thought.

Image from Michael Demson's Masks of Anarchy, a brilliant graphic novel that can be purchased here.

Shelley Lives!

The reaction of the protestors was mixed. Many of them were simply bemused, but I did draw a small round of applause at one point. More gratifyingly were the people who came up to me and enquired further about the poems which fulfilled a central aim of piquing interest. One person in particular wanted me to place Shelley in the historical sweep of radical dissent. The surprising and depressing fact was that he was an English History graduate for whom radicalism was presented as a half-hearted account of Marxism in the 19th Century! The majestic sweep and variety of radical thought over four centuries had largely passed him by – what an indictment of the education system.

Will I continue – absolutely! The sense of catharsis may have just been simply the result of over-oxygenation of course, but the surge of energy was wonderful. It was also a humbling experience to be a vessel for ideas and emotions far beyond my own abilities to articulate. I felt a great sense of connection, as though the past two centuries had simply evaporated and the man himself was still amongst us. I discovered patterns and connections which had not occurred to me when reading the material quietly and alone. I hope Shelley would have approved of what I had done to his poetry.

For me the work of Shelley is not an artifact to be studied and analyzed but a continuing personal inspiration for my political engagement. I am sure it will be the same for many more people when we release him from the sanitized, gilded cage in which the establishment has trapped him.

Let me tell you something Mark, Shelley, who went to his grave without seeing Mask of Anarchy published, would be overjoyed. Overjoyed because he wrote his poetry to inspire people to change the world the way you have been inspired. But I think his joy would be profoundly tinged with sadness, a sadness which stems from the realization that the world has not changed so very much from his times; the poor are still oppressed, and the rich have grown ever wealthier. Shame on us all.

Mark's article can be found here at his terrific website, New Leveller. It is reprinted with his permission. The banner image at the top of the post comes from Michael Demson's Masks of Anarchy, abrilliant graphic novel that can be purchased here.

Revolutionary Politics and the Poet. By Mark Summers

What I love about Mark Summers' writing is his ability to put Shelley in the context of his time, and then make what happened then feel relevant now. Both Mark and I sense the importance of recovering the past to making sense out of what is happening today. With madcap governments in England and the United States leading their respective countries toward the brink of authoritarianism, Shelley's revolutionary prescriptions are enjoying something of a renaissance; and so they should, we need Percy Bysshe Shelley right now!

One of the goals of my site is also to gather together people from all disciplines and walks of life who are interested in Shelley. One such person is Mark Summers. You have encountered his writing here before. One of Mark's stated goals is to "take Shelley to the streets". I have more to report about this later. There has been a long history of this, most recently during the Occupy Wall Street demonstrations. Mark is an e-Learning specialist for a UK Midlands based company and a musician specializing in experimental and free improvised forms. An active member of the Republic Campaign which aims to replace the UK monarchy with an accountable head of state, Mark blogs at at www.newleveller.net which focuses on issues of republicanism and radical politics/history. You can also find him on Twitter @NewLeveller. Mark's writing has a vitality and immediacy which is exhilarating. I first discovered him as a result an article of his which appeared in openDemocracy. I re-published here recently.

What I love about Mark Summers' writing is his ability to put Shelley in the context of his time, and then make what happened then feel relevant now. Both Mark and I sense the importance of recovering the past to making sense out of what is happening today. With madcap governments in England and the United States leading their respective countries toward the bring of authoritarianism, Shelley's revolutionary prescriptions are enjoying something of a renaissance; and so they should, we need Percy Bysshe Shelley right now!.

What comes next is Mark's follow-up to his important openDemocracy piece. Mark wrote his article in the summer of 2016; since then Donald Trump was elected President of the United States - making Mark's article prescient and even more compelling. Enjoy!

Revolutionary Politics and the Poet

"Ye are many, they are few!"

The anniversary of two events of primary importance in England's radical history occur in August; the birth of poet Percy Bysshe Shelley on the 4th (in 1792) and the Peterloo Massacre in Manchester, England on the 16th (in 1819). Last summer (27 July 2016) my thoughts Shelley’s great Poetical Essay on the State of Things was published on openDemocracy and it is a suitable moment to consider the relevance of another of his great works inspired by events in Manchester, the Mask of Anarchy (you can read it here). Like the openDemocracy article, this post is neither intended as a literary study of Shelley’s work nor an account of the origins of Shelley’s radical opinions. There are many people far better qualified for this task and I can only draw your attention to two examples, Paul Foot’s excellent article from 2006 or the materials on this fascinating blogsite by Graham Henderson. In both my openDemocracy article and the present post I have two aims. Firstly to outline my claim to Shelley as part of the tradition with which I identify and secondly to assess the importance of Shelley’s work and the invaluable lessons it has for us now.

Although popular pressure had been building for reform since the start of the French Revolution in 1789, economic depression and high unemployment following the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 intensified demands for change. In 1819 a crowd variously estimated at being between 60,000 and 100,000 had gathered in St Peters Field in Manchester to protest and demand greater representation in Parliament. The subsequent overreaction by Government militia forces in the shape of the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry led to a cavalry charge with sabres drawn. The exact numbers were never established but about 12 to 15 people were killed immediately and possibly 600-700 were injured, many seriously. For more information on the complex serious of events, go to this British Library resource and this campaign for a memorial. [Editor's note: For more on the Mask of Anarchy, follow this link to my review of Michael Demson's graphic novel, Masks of Anarchy]

Shelley was in Italy when news reached him of the events in Manchester and he set down his reaction in the poem Mask of Anarchy which contains the immortal lines contained in the title of my post. The work simmers over 93 stanzas with a barely controlled rage leading to a call to action and a belief that the approach of non-violent resistance (an approach followed by Gandhi over a century later) would allow the oppressed of England to seize the moral high ground and achieve victory. Such was the power of the poem that it did not appear in public until 1832, the year of the Great Reform Act which extended the voting franchise.

Detail from Michael Demson's Masks of Anarchy.

Anarchy – Chaos and Confusion as a Method of Control

An excellent place to start thinking about the relevance of the poem is with the eponymous evil villain, Anarchy. He leads a band of three tyrants which are identified as contemporary politicians, Murder (Foreign Secretary, Viscount Castlereagh), Fraud ( Lord Chancellor, Lord Eldon) and Hypocrisy (Home Secretary, Lord Sidmouth). But Shelley widens the cast of villains in his description to include the Church, Monarchy and Judiciary.

Last came Anarchy : he rode

On a white horse, splashed with blood ;

He was pale even to the lips,

Like Death in the Apocalypse.

And he wore a kingly crown ;

And in his grasp a sceptre shone ;

On his brow this mark I saw—

‘I AM GOD, AND KING, AND LAW!’

The promotion of anarchy with its attendant fear of chaos and disorder was one of the most serious accusations which could be levelled at authority. The avoidance of anarchy was also a concern of English radicals ever since the Civil War in the 1640s and Shelley was making the gravest personal attack with his explicit individual accusations. But Shelley’s attack is pertinent, the implicit threat of confusion and chaos to subdue a population for political ends is something which we experience today. The feeling of powerlessness which can result from an apparently confusing and chaotic situation is something which the documentary filmmaker Adam Curtis has termed ‘oh dearism’. In our own time he has identified recent Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne as deliberately using such a tactic. Likewise the Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn has been variously accused of being a threat to national security or a threat to the economy .

The 1819 Peterloo massacre occurred at a time of heightened external tension with fear that the French revolution would spread to Britain. The fear was not unfounded and various groups around the country emerged with such an intent, in many cases inspired by Tom Paine’s The Rights of Man which the Government had been trying to unsuccessfully suppress. The existence of an external threat combined with homegrown radicals was explicitly used as a reason for a policy of political repression and censorship. Likewise today an external threat, Islamic State combined with an entirely separate perceived internal threat (employee strike action) has been cited as justification for a whole range of measures including invasive communication monitoring (so called ‘Snoopers Charter’) without requisite democratic controls and a repressive Trade Union Bill seeking to shackle the ability of unions to garner support and carry out industrial action.

Detail from Michael Demson's Masks of Anarchy.

The Nature of Freedom

The nature of freedom is a problem which has bothered both libertarians and republicans for generations. In Mask of Anarchy where Shelley is enumerating the injustice suffered by the poor he clearly defines freedom in terms of the state of slavery, a core republican premise:

What is Freedom? Ye can tell

That which Slavery is too well,

For its very name has grown

To an echo of your own

The essence of freedom which has financial independence as a core component is clearly articulated over a number of stanzas, starting with:

‘’Tis to work and have such pay

As just keeps life from day to day

In your limbs, as in a cell

For the tyrants’ use to dwell,

‘So that ye for them are made

Loom, and plough, and sword, and spade,

With or without your own will bent

To their defence and nourishment.

In our own time freedom is frequently constrained by insufficient financial resources as a result of hardship caused by issues such as disability support cuts, chronic low wages and a zero-hours contract society. Shelley would have no problem with identifying Sports Direct owner Mike Ashley, playing with multi-million pounds football clubs while his workforce toil in iniquitous conditions for a pittance; or Sir Philip Green impoverishing British Home Stores pensioners to pile up a vast fortune for his wife in Monaco.

Disgustingly the only thing we need to update from Shelley's Mask of Anarchy is the cast of villains, the substance is unchanged!.

Non-Violent Resistance – A Way Forward

I pointed out that in the 1811 Poetical Essay, Shelley was searching for a peaceful way to elicit change in an oppressive hierarchical society. By 1819 Shelley has settled on his preferred solution of non-violent resistance.

Stand ye calm and resolute,

Like a forest close and mute,

With folded arms and looks which are

Weapons of unvanquished war,

‘And let Panic, who outspeeds

The career of armèd steeds

Pass, a disregarded shade

Through your phalanx undismayed.

Nonviolent resistance is not an instant solution and takes years of persistent and widespread enactment to be successful. A partial victory was secured in the 1830s with the Great Reform Act (1832) and the Abolition of Slavery Act (1834). But history has proved that it is a viable strategy, the independence of India being an eloquent testament.

Detail from Michael Demson's Masks of Anarchy.

This article is republished with the kind permission of the author. It appeared originally on Mark's superb blogsite (www.newleveller.net) on 7 August 2016.

- Mary Shelley

- Anna Mercer

- Coleridge

- An Address to the Irish People

- Richard Carlile

- Jonathan Kerr

- William Wordsworth

- Queen Mab

- David Carr

- The Last Man

- Harriet Shelley

- Eleanor Marx

- Industrial Workers of the World

- A Philosophical View of Reform

- Joe Hill

- The Easter Rising

- When the Lamp is Shattered

- Richard Margraff Turley

- Henry Salt

- Buxton Forman

- Lord Sidmouth

- Valperga

- Daisy Hay

- Frankenstein

- Mask of Anarchy

- Peterloo

- Michael Demson

- William Godwin

- Byron

- Pauline Newman

- Mutability

- Epipsychidion

- Thomas Paine

- Mont Blanc

- Mark Summers

- Paul Foot

- George Bernard Shaw

- Chartism

- Diodati

- Timothy Webb

- Mary Wollstonecraft

- Defence of Poetry

- free media

- Daniel O'Connell

- Vindication of the Rights of Women

- Ginevra

- Jacqueline Mulhallen

- Edward Dowden

- Robert Southey

- Chamonix

- James Connolly

- Edward Aveling

- Claire Clairmont

- Levellers

- England in 1819

- Lynn Shepherd

- To Autumn

- Alastor

- Ozymandias

- Francis Burdett

- Kenneth Neill Cameron

- Thomas Kinsella

- Tess Martin

- Geneva

- Proposal for an Association

- Cenci

- Kathleen Raine

- Richard Emmet

- Martin Bodmer

- Sonia Liebknecht

- Radicalism

- Keats-Shelley Association

- Trotsky

- Isabel Quigley

- Alien

- Michael Gamer

- Maria Gisborne

- World Socialism Web Site

- Theobald Wolfe Tone

- Butcher's Dozen

- Percy Shelley

- Freidrich Engels

- Milton

- Blade Runner

- ararchism

- Paul Bond

- Rosa Luxemburg

- Masks of Anarchy

- Keats-Shelley Review

- John Keats

- Leigh Hunt

- A Defense of Poetry

- Humphry Davy

- perfectibility

- Henry Hunt

- Paradise Lost

- Political Justice

- Shelley Society

- Polidori

- Necessity of Atheism