Atheist, Lover of Humanity, Democrat

PERCY BYSSHE SHELLEY

Eleanor Marx Battles the Shelley Society!

In April of 1888, Eleanor Marx and Edward Aveling delivered a Marxist evaluation of the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley to an institution known as “The Shelley Society”. Composed of some of the giants of the Victorian literary community, the Society undertook research, hosted speeches, spawned local affiliates, republished important articles and poems (some for the first time!) and even produced Shelley’s The Cenci for the stage. But the Shelley Society was also a vehicle seemingly designed to obliterate Shelley’s left-wing politics. This article examines why the Shelley Society came into being and how it influenced the reception of Shelley for generations to come. Go behind the scenes with me as Eleanor Marx battles the forces of the male, bourgeois, Victorian literary establishment.

Eleanor Marx Battles the Shelley Society!

Eleanor Marx

In 1886, at the height of the Victorian era, a group of admirers of Percy Bysshe Shelley came together to form the Shelley Society. Among the founders were some of the intellectual giants of the age. For example, the list of distinguished names includes Edward Dowden, Buxton Forman, William Michael Rossetti, Arthur Napier (the Merton Professor of English Language and Literature at Oxford), Dr. Richard Garnett, George Bernard Shaw, Henry Salt, William Bell Scott (whose gorgeous painting of Shelley’s grave hangs in the Ashmolean Museum), Algernon Charles Swinburne, Francis Thompson, the Rev. Stopford Brooke, Edward Aveling and Eleanor Marx - to name only a few. At inception there were just over 100 but this number soon swelled to over 400 members. In addition, members of the general public were allowed to attend the meetings. As a result, while the inaugural lecture had an audience of over 500 - only a small proportion of whom were actual paid members. As it grew, the Society came to have chapters around the world. One thing that to me stands out from the list of eminent names, is what amounts to an ideological left/right fault-line which is at the heart of our story. And it actually speaks to Shelley’s protean character that he would find passionate adherents on both ends of the political spectrum.

A useful history of the literary societies of the 1880s (Shelley’s was not the only one) can be found in Angela Dunstan’s article, ‘The Newest Culte’: Victorian Poetry and the Literary Societies of the 1880s (In Nineteenth-Century Literature in Transition: The 1880s, edited by Penny Fielding and Andrew Taylor and published in 2019 by Cambridge). Dunstan points out that

“Though many in the Society were eminent literary scholars or critics the Notebooks make a concerted effort to legitimate opinions and close readings of rank and file members, demonstrating the capacity of vernacular poetry to be seriously studied by professional scholars and amateur enthusiasts alike.”

Also apparent to anyone reading through the Society proceedings is the presence of female voices. Dunstan writes,

Women were active in the Shelley society; notices of their involvement were regularly printed in “Ladies’ Columns:” in the press and reprinted in the Notebooks, and female members certainly attended the Society’s activities that contributed to debates. The Notebooks evidence debates over close readings of Alastor, for example, where ordinary female speakers confidently take on George Bernard Shaw or William Michael Rossetti over interpretation, and it is this democratic nature of literary societies’ debates which many outside of the societies and particularly in the universities found threatening.

“A stuffy Victorian, bourgeois morality suffuses the written record of the Society’s meetings.”

The Society published notes of its meeting, undertook research, hosted speeches, spawned local affiliates, republished important articles and poems (some for the first time!) and even produced Shelley’s The Cenci for the stage — all before it fell apart four years later. The goal was to make the scholarly study of Shelley more accessible to the general public - to in effect popularize Shelley and “democratise” literary criticism - and the meetings gained a reputation for an interest in critical rather than mere biographical exercises. Though largely forgotten by history, the proceedings of the Shelley Society constituted a momentous episode in the history of Shelley’s reception by the reading public; though one that is not without controversy.

Some, notably the socialist Paul Foot, were of the view that the Society had a deleterious effect on his reputation as a political radical. That said, Professor Alan Weinberg has noted that

We are reminded that prominent members of the Shelley Society present at the inaugural lecture were not averse to the poet's politics. If anything they tended to advance them. Succeeding lectures were devoted to Queen Mab (Forman), Prometheus Unbound(Rossetti), The Triumph of Life (Todhunter), The Mask of Anarchy (Forman), The Hermit of Marlow and Reform (Forman), Shelley and Disraeli's politics (Garnett) -all of which point positively or constructively to Shelley's radical sentiments.

The Rev. Stopford Brooke, 1885

The first speech at the inaugural meeting of the Society was delivered by the Reverend Stopford Augustus Brooke. Brooke was a prominent member of the Church of England who had risen to the post of “chaplain in ordinary” to Queen Victoria in 1875. He was a patron of the arts and was the leading figure in raising the money to acquire Dove Cottage (now administered by the Wordsworth Trust). In 1880, Brooke took the unusual step of seceding from the church because he no longer subscribed to its principal dogmas. In that same year Brooke also published a collection of Shelley’s poetry, Poems from Shelley, selected and arranged by Stopford A. Brooke (London: Macmillan & Co., 1880). In the speech, Brooke principally responds to the attacks on Shelley’s character that had been famously leveled by Mathew Arnold - opinions which have poisoned Shelley’s reception to the present day. The Society, said Brooke, desired to

“connect together all that would throw light on the poet’s personality and his work, to ascertain the truth about him, to issue reprints and above all to do something to further the objects of Shelley’s life and works, and to better understand and love a genius which was ignored and abused in his own time, but which had risen from the grave into which the critics had trampled it to live in the hearts of men.”

Matthew Arnold

Brooke also devoted considerable attention to rebutting the opinions of perhaps Shelley’s most effective critic, Matthew Arnold. Arnold’s judgement on Shelley was, Brooke thought, “victimized by his personal antipathy to Shelley’s idealism”, and Brooke found his views “petulant” and “prejudiced”. While others had attacked Shelley, none of them had the gravitas and influence of Mathew Arnold; Arnold who had characterized Shelley as a “beautiful and ineffectual angel, beating in the void his luminous wings in vain”. Arnold’s critique of Shelley appeared in a pair of essays written on Byron and Shelley and which were published together in his Essays in Criticism, Second Series (1888). You can find a beautifully written, approachable essay on the subject written by Professor Alan Weinberg here. Arnold’s encapsulation of Shelley’s character went on to have enormous influence. Weinberg:

On close examination (as will be shown), his [Arnold’s] argument is grossly superficial and unreliable. What has tended to carry weight is the authority of Arnold's position as eminent critic of his age (while this had currency) and the persuasiveness of his dictum which has connected with an ongoing antipathy or ambivalence towards Shelley. In the course of time, the dictum has become disentangled from the original argument and has acquired a life of its own.

Despite Professor Weinberg’s opinion expressed above, it is my view that Shelley’s radical politics were at best tolerated by Society members. It seems to me that from inception, there was a not so hidden agenda which came to dominate the Society’s proceedings. In seeking the “truth about Shelley”, Brooke for example proposed a distinctly religious and spiritual approach saying that Shelley’s “method was the method of Jesus Christ, reliance on spiritual force only…” Brooke saw Shelley’s life as “full of natural piety” and “noble ideals” while at the same times characterising his “aspirations” as “often unreal and visionary.” He saw Shelley as a man “not content with the world the way as it is” (fair enough) but as a “prophetic singer of the advancing kingdom of faith and hope and love.” (more problematic). A stuffy Victorian bourgeois morality suffuses the written record of the Society’s meetings. That morality even appears to have influenced membership applications. Henry Salt records that when Edward Aveling (a socialist living out of wedlock with the daughter of Karl Marx) attempted to join the Society, his application was turned down by a majority of members - “his marriage relations being similar to Shelley’s”. It was only through the “determined efforts” of William Michael Rossetti that the decision was over-turned (Yvonne Kapp, Eleanor Marx, p 450).

Frederick James Furnivall. William Rothenstein (attributed), Trinity Hall

Frederick James Furnivall, a prominent “Christian Socialist” who founded the London Working Men’s College and was a tireless promoter of English literature, lauded Brooke’s impassioned remarks by declaring that the Shelley Society would devote itself to responding to what he characterized as “Philistine” attacks on Shelley’s character and poetry. The chief “Philistine” referenced here was Cordy Jeaffreson who had recently authored a highly critical biography of Shelley: (The Real Shelley: New Views of the Poet's Life, 2 vols. 1885). What we see playing out here was a curious contest between rival camps to stake out exactly who the “real” Shelley was and just importantly, what he believed.

The Society’s goal, then, was not only to rebut attacks of Shelley, but also to find the “real Percy Bysshe Shelley”. Now, this is a mission which frankly resonates with me! However, at the hands of the Society, a very unusual, apolitical, quasi-religious Shelley would emerge as “real” Shelley. For his part, this would probably have come as an enormous surprise to Shelley himself - the self-declared atheist, humanist and republican who once wrote, "I tell of great matters, and I shall go on to free men's minds from the crippling bonds of superstition.” This battle for the soul of the “real” Percy Bysshe Shelley has never really gone away and it had real world consequences for me - something I wrote about in My Father’s Shelley - a Tale of Two Shelleys.

“I tell of great matters, and I shall go on to free men’s minds from the crippling bonds of superstition.”

However, the Society didn’t just want a new, more religiously-minded Shelley, whose “rotten ethics” (see below) had been explained away as youthful folly. Notwithstanding the fact that Society members had a somewhat permissive or indulgent attitude toward Shelley’s radicalism (Weinberg, above), there was nonetheless a distinct tendency to in effect depoliticise Shelley. For example, in a lecture to the Society on 14 April 1886, Buxton Forman complained that,

“Shelley is far more widely known as the author of Queen Mab than as the author of Prometheus Unbound. As the latter really strengthens the spirit while the former does not, we, who reverence Shelley for his spiritual enthusiasm, desire to see all that changed. And the change is advancing.“

The battle lines were clearly drawn. This fight was going to be about more than poetry; it was going to be about politics and it was going to be about class. A major stumbling block for the bourgeois members of the Society was clearly Shelley’s professed atheism. But there were ways to deal with this. Francis Thompson, for example, devoted a significant portion of his famous 1889 essay, Shelley, opining that Shelley could not really have been an atheist - because he was “struggling - blindly, weakly, stumblingly, but still struggling - toward higher things.” He had just died before he got there. While we might question the robustness of this evidence, his final argument was air-tight: “We do not believe that a truly corrupted spirit can write consistently ethereal poetry…The devil can do many things. But the devil cannot write poetry.”

Sara Coleridge daughter of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and an arch, bourgeois Victorian, reflected a widespread view when she wrote to a friend,

Sara Coleridge

"You are more displeased with Shelley's wrong religion than with Keats' no religion. Surely Shelley was as superior to Keats as a moral being, as he was above him in birth and breeding. Compare the letters of the two . . . see how much more spiritual is Shelley's expression, how much more of goodness, of Christian kindness, does his intercourse with his friends evince.”

One might well think that with friends like this, who needs enemies? I am not sure what is worse: the cringe-worthy dismissal of Keats, or the complete misappropriation of Shelley. And indeed, on another occasion one of the attendees said almost exactly that. Having listened to a speech about Shelley by Edward Silsbee that struck her as more of a “homily” than literary criticism, a Mrs. Simpson remarked that had Shelley heard the speech, he might well have said, “Save me from my friends.” Silsbee was reminded by another listener that between Dante and Shelley there was in fact another poet by the name of Shakespeare. Hagiography was very much the order of the day it would appear.

By the time the bourgeois members of the Shelley Society had finished with Shelley, poems like Queen Mab had been successfully relegated to the back pages of collected editions under the heading “Juvenilia“ - a designation suggested by Forman himself. Thus a cordon sanitaire had been established - Shelley’s radicalism was “ring-fenced”. He had in effect been reclaimed by proper society.

“The battle lines were clearly drawn. This fight was going to be about more than poetry; it was going to be about politics and it was going to be about class. ”

Why was this happening? Well, Shelley an important poet. But he had two very distinct and mutually antagonistic audiences - both loved him and for very different reasons. On the one hand was the working class and its socialist champions. On the other? The upper class who valued above all Shelley’s “spiritualism”, his love poetry and his lyricism. The two could have probably co-existed but for the annoying fact that Shelley himself was ill-fitted to the bourgeois camp. That and the fact Shelley was actually a revolutionary who had set himself implacably against them - most of his output was intensely political and revolutionary.

Karl Marx and his daughters with Engels.

Bourgeois Victorian literary society in the main objected Shelley’s radical heritage. They wanted to shift focus from this unwelcome aspect of his poetry and in this regard, his prose was for the most part ignored. Though perhaps presciently, it was Arnold who observed that Shelley’s letters and essays might better resist the “wear and tear of time” and “finally come to stand higher that his poetry”. Instead the focus was to shift to Shelley’s “mysticism”, his “spiritual enthusiasm” and above all his “lyricism”. Shelley’s political poetry was considered to be almost an aberration and a defect of character and grist for the “street socialists.”

For a glimpse into what they were reacting against, here is the view from the left (seemingly directly in response to the activities of the Shelley Society), courtesy of Friedrich Engels:

"Shelley, the genius, the prophet, finds most of [his] readers in the proletariat; the bourgeoisie own the castrated editions, the family editions cut down in accordance with the hypocritical morality of today.”

According to Eleanor Marx, her father,

“who understood the poets as well as he understood the philosophers and economists, was wont to say: “The real difference between Byron and Shelley is this: those who understand them and love them rejoice that Byron died at thirty-six, because if he had lived he would have become a reactionary bourgeois; they grieve that Shelley died at twenty-nine, because he was essentially a revolutionist, and he would always have been one of the advanced guard of socialism.”

Our story begins in earnest during the spring of 1887 when in a speech to the Society on 13 April one of the members, Alexander G. Ross delivered a bitter, class-based attack not upon Shelley himself, but upon Shelley’s socialist proponents. According to Paul Foot, Ross had been “enraged to discover that workers and even socialists were quoting a well-known English poet to their advantage”. Worse, of course, was the fact that Ross believed that Shelley’s “ethics were rotten.” As did many of his bourgeois colleagues.

“...they grieve that Shelley died at twenty-nine, because he was essentially a revolutionist, and he would always have been one of the advanced guard of socialism.””

Ross approached the issue by arguing that while,

“…no one can contest the right of anyone even though he may be a mere sans culotte who runs about with red rag, to quote Shelley when or where he pleases; but when the blatant and cruel socialism of the street endeavours to use the lofty and sublime socialism of the study for its own base purpose it is time that with no uncertain sound all real lovers of the latter should disembowel any sympathy with the former….It will be clearly understood that I strongly protest against any Imaginative writer being cited as an authority in favour of any political or social action…”

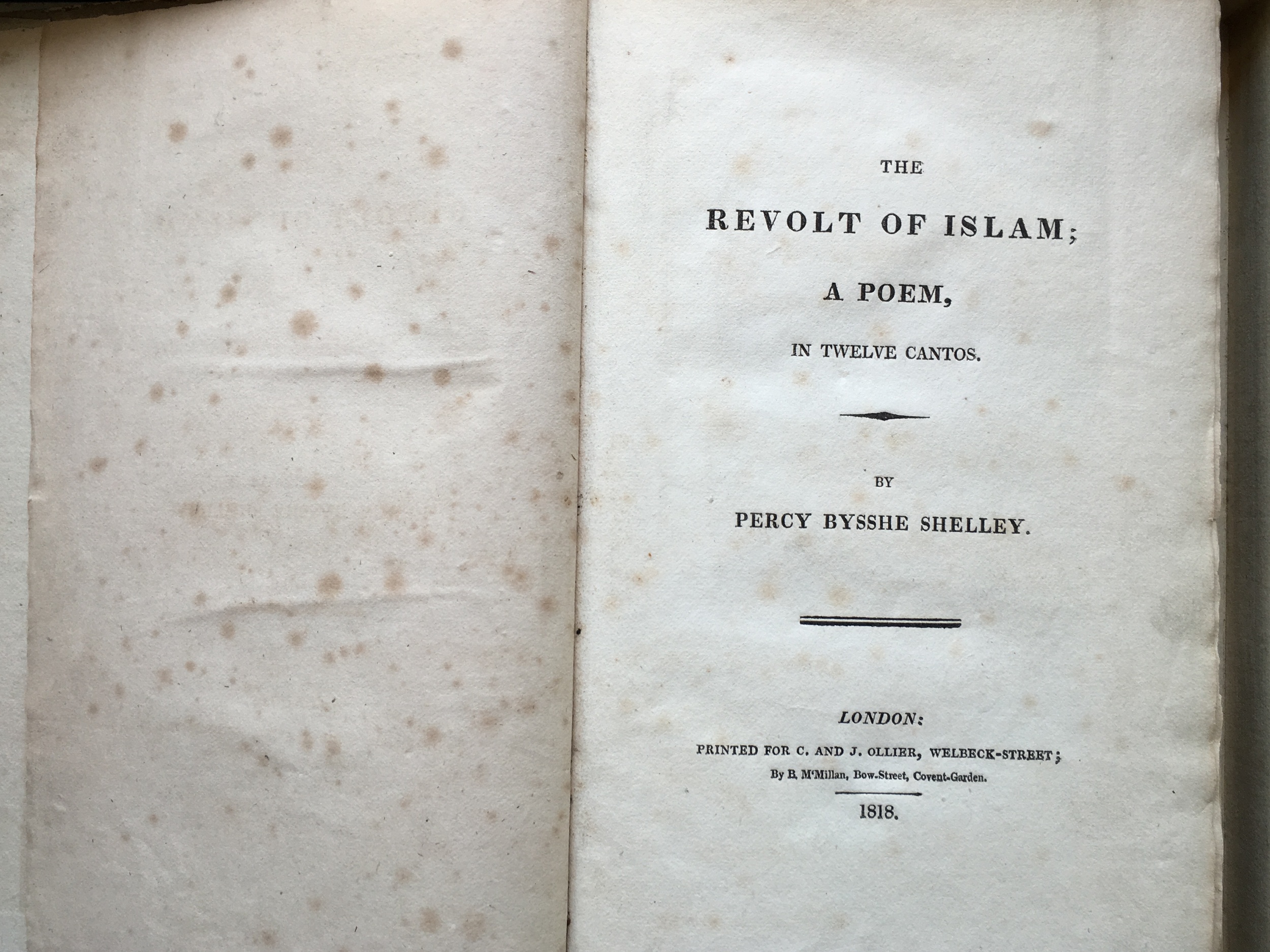

Edward Aveling

The distinction between “parlour socialism” and socialism actually put into action (“street socialism”) is quite something. Poetry was to be for poetry’s sake - and to hell with the politics. Now, in fairness, it is to be pointed out that both Rossetti and Furnivall both objected to elements of Ross’s address. Rossetti noted that a “great poet should put morals into his writings”, while carefully reinterpreting the Revolt of Islam’s message as “do good to your enemies; an annunciation of a universal reign of love.” The Revolt of Islam he concluded was “certainly not a didactic poem”. Furnivall complained that Ross seemed to treat poetry as a “toy”, and averred that “poets were men who felt certain truths more deeply than other men, and it was their work to put forth those thoughts.” Three of the avowed socialists in the room, Henry Salt, Aveling and George Bernard Shaw objected more specifically to the attacks on socialism.

Aveling, for his part, maintained that “the socialism of the study and the street was one and the same thing – and that constituted the beauty of modern socialism.” Shaw was highly critical as well, arguing that “a poem ought to be didactic, and ought to be in the nature of a political treatise - for poetry was the most artistic way of teaching those things a poet ought to teach.” One of the oddities of the debate turns on the argument about whether Shelley’s poetry was “didactic” or not. It will help modern readers if we unpack the coded language here. Opponents of Shelley’s didacticism were really reacting to his politics; or to be more accurate, the fact that socialists were championing him and as Paul Foot suggested, doing so to their advantage - in other words advancing the cause of socialism.

Annie Besant

Ross’s contentious address prompted Aveling and Marx to request an opportunity to present the case for an alternative version of the “Real Shelley”; a case for the “Socialist Shelley”. To them, what was happening in the 1880s was, plainly, a battle for the legacy of Percy Bysshe Shelley. Viewed from the left, the stakes would have been remarkably high. Marx and Aveling saw Shelley as someone who saw more clearly than anyone else “that the epic of the nineteenth century was to be the contest between the possessing and the producing classes.” This insight removed him “from the category of Utopian socialists and [made] him as far as was possible in his time, a socialist of modern days.” To see Shelley “castrated” (in the words of Friedrich Engels) and co-opted by the bourgeoisie was a call to arms. Aveling delivered the paper in April of 1888 though was careful to point out that “although I am the reader, it must be understood that I am reading the work of my wife as well as, no, more than, myself.”

Eleanor Marx was an extraordinary person who deserves far more attention from our modern society. According to Harrison Fluss and Sam Miller writing in Jacobin, Marx was

born on January 16, 1855, Eleanor Marx was Karl and Jenny Marx’s youngest daughter. She would become the forerunner of socialist feminism and one of the most prominent political leaders and union organizers in Britain. Eleanor pursued her activism fearlessly, captivated crowds with her speeches, stayed loyal to comrades and family, and grew into a brilliant political theorist. Not only that, she was a fierce advocate for children, a famous translator of European literature, a lifelong student of Shakespeare and a passionate actress.

To which we can add that she was also devotee of and influenced by Percy Shelley. Both Eleanor and Aveling were immersed in culture - much like Karl Marx himself. This was not Aveling’s first foray into the subject matter. In 1879 he had given a speech about Shelley to the Secular Society - described by Annie Besant as a “simple, loving, and personal account of the life and poetry of the hero of the free thinkers..” (Kapp, p. 451) This assessment, by the way, is yet another indication of the high regard accorded to Shelley by the socialist community. According to her Wikipedia entry, Besant was was a

“British socialist, theosophist, women's rights activist, writer, orator, educationist, and philanthropist. Regarded as a champion of human freedom, she was an ardent supporter of both Irish and Indian self-rule. She was a prolific author with over three hundred books and pamphlets to her credit.”

That she considered Shelley to be the “hero of freethinkers” is telling and a further reminder of the influence Shelley had on 19th century socialists. Kapp perceptively points out that:

“There can be no doubt that this lecture, though delivered by Aveling, was it to collaboration between two people who had long and devotedly studied the poet with equal enthusiasm, Aveling primarily as an atheist, Eleanor as a revolutionary…”

Eleanor Marx at 18

Marx and Aveling were at pains to point out that “the question to be considered…is not whether socialism is right or wrong, but whether Shelley was or was not a socialist.” Thus they first described a set of six distinguishing hallmarks of socialism and pointed out, “…If he enunciated views such as these, or even approximating to these, it is clear that we must admit that Shelley was a teacher as well as a poet.” The authors then set out their course of study:

(1) A note or two on Shelley himself and his own personality, as bearing on his relations to Socialism;

(2) On those, who, in this connection had most influence upon his thinking;

(3) His attacks on tyranny, and his singing for liberty, in the abstract;

(4) His attacks on tyranny in the concrete;

(5) His clear perception of the class struggle; and

(6) His insight into the real meaning of such words as “freedom,'’ “justice,” “crime,” “labour,” and “property”.

Of Shelley’s personality, Marx and Aveling seem principally interested in adducing (with copious citations from The Cenci, Prince Athanese, Queen Mab, Laon and Cythna and Triumph of Life) Shelley’s connection to the politics of his era, noting his advanced thinking on issues such as Napoleon and evolution:

“Of the two great principles affecting the development of the individual end of the race, those of heredity and adaptation, he had clear perception, although day as yet we are neither accurately defined nor even named. He understood that men and peoples were the result of their ancestry and their environment.”

As for Shelley’s influences, the authors begin by contrasting Shelley with Byron.

In Byron they suggest,

“…we have the vague, generous and genuine aspirations in the abstract, which found their final expression in the bourgeois-democratic movement of 1848. In Shelley, there was more than the vague striving after freedom in the abstract, and therefore his ideas are finding expression in the social-democratic movement of our own day….He saw more clearly than Byron, who seems scarcely to have seen it at all, that the epic of the nineteenth century was to be the contest between the possessing and the producing classes. And it is just this that removes him from the category of Utopian socialists, and makes him so far as it was possible in his time, a socialist of modern days.

They then enumerate those whom they consider his prime influences: François-Noël Baboeuf, Rousseau, the French philosophes, the Encyclopaedists, Baron d’Holbach, and Denis Diderot. The addition of Diderot to this list is interesting. We now know that as early as 1812, Shelley had ordered copies of Diderot’s works - but this was not widely known in the 19th Century. I certainly feel that the spirit of Diderot suffuses Shelley’s philosophy and writings. Interestingly, Aveling and Marx thought very highly of Diderot as well, averring that Diderot “was the intellectual ghost of everybody of his time” - an assessment described to me as a “penetrating insight” by Andrew Curran the author of the excellent Diderot and the Art of Thinking Freely.

“We simply can not underestimate the influence Shelley had on the socialists of this period.”

Godwin was also singled out, hardly surprisingly - though as Marx and Aveling ruefully note, “Dowden’s Life has made us all so thoroughly acquainted with the ill-side of Godwin that just now there may be a not unnatural tendency to forget the best of him.” But of real interest is the time spent adducing the under-appreciated influence of “the two Marys” (Wollstonecraft and Godwin), and the perspective is instructive. “In a word,” Marx and Aveling suggest,

the world in general has treated the relative influences of Godwin on the one hand and of the two women on the other, pretty much has might have been expected with men for historians. Probably the fact that he saw so much through the eyes of these two women quickened Shelley's perception of woman's real position in society and the real cause of that position….this understanding…is in a large measure due to the two Marys.

Shelley’s espousal of what we would now call feminist causes was extremely unusual for his time. Clearly it resonated with Marx and Aveling who comment that “it was one of Shelley's "delusions that are not delusions" that man and women should be equal and united. And Paul Foot seizes on and develops this theme in his speech to the 1981 Marxism Conference in London.

“It’s not just that he saw that women were oppressed in the society, that the women were oppressed in the home; it’s not just that he saw the monstrosity of that. It’s not even just that he saw that there was no prospect whatever of any kind for revolutionary upsurge if men left women behind. Like, for example, in the 1848 rebellions in Paris where he men deliberately locked the women up and told them they couldn’t come out to the demonstrations that took place there because in some way or other that would demean the nature of the revolution. It wasn’t just that he saw the absurdity of situations like that. It was that he saw what happened when women did activate themselves, and did start to take control of their lives, and did start to hit back against repression. Shelley saw that what happened then was that again and again, women seized the leadership of the forces that were in revolution! All through Shelley’s poetry, all his great revolutionary poems, the main agitators, the people that do most of the revolutionary work and who he gives most of the revolutionary speeches, are women. Queen Mab herself, Asia in Prometheus Unbound, Iona in Swellfoot the Tyrant, and most important of all, Cythna in The Revolt of Islam. All these women, throughout his poetry, were the leaders of the revolution and the main agitators.”

I have written myself at length on the fact that much of Shelley’s radicalism concentrates on what he would have considered twinned targets: the monarchy and religion (religion being for Shelley the “hand-maiden of tyranny”). So it is not surprising that when Marx and Aveling came to the third part of their presentation, they pointed out that at the root of Shelley’s antagonism to the tyranny of church and state was the belief that the ultimate problem was

“the superstitious in the capitalistic system in the empire of class…. And always, every word that he has written against religious superstition and the despotism of individual rulers may be read as against economic superstition and the despotism of class.”

They also pointed out the extent to which Shelley’s concern with tyranny was more than just abstract, he is lauded not just for his attention to Mexico, Spain, Ireland and England, but also for his attacks on individuals: Castlereagh, Sidmouth, Eldon and Napoleon. “He is forever,” they wrote, “denouncing priest and king and statesman.”

Of most interest to me is the fourth section in which Marx and Aveling turn to Shelley’s understanding of “class struggle.” What makes Shelley a socialist more than anything else,

“is his singular understanding of the facts that today tyranny resolves itself into the tyranny of the possessing class over the producing, and that to this tyranny in the ultimate analysis is traceable almost all evil and misery. He saw that the soul-called middle class is the real tyrant, the real danger at the present day.”

Shelley by George Clint after Amelia Curran

To support this position, a veritable arsenal of quotations is deployed. From what they call the Philosophic View of Reform, from Godwin, from letters to Hookham and Hitchens, and from Swellfoot the Tyrant, Peter Bell the Third and Charles the I. The effect is spectacular. For example, this from Swellfoot: “Those who consume these fruits through thee [the goddess of famine] grow fat. / Those who produce these fruits through the grow lean". The cumulative effect is to place Shelley in a tradition that leads directly to Marx, Engels and modern socialism. And, indeed, the resonance and reverberation of the language is uncanny.

Marx and Aveling conclude the section by quoting Mary to great effect (from her notes to her collected edition): “He believed the clash between the two classes of society was inevitable, and he eagerly ranged himself on the peoples side.” They clearly see Shelley as a direct precursor to Marx and Engels and it is hard to disagree with them. In an unusual turn of phrase considering their undoubted atheism, they had earlier referred to Shelley as a philosopher and a prophet - a term you will have seen Engels use as well in the quotation cited above. Elsewhere, Marx and Aveling refer to him as the “poet-leader”. In a truly remarkable passage they seem to treat Shelley’s writing, his value system, almost as a “sacred text”:

This extraordinary power of seeing things clearly and of seeing them in their right relations one to another, shown not alone in the artistic side of his nature, but in the scientific, the historical, the social, is a comfort and strength to us that hold in the main the beliefs, made more sacred to us in that they were his, and must give every lover of Shelley pause when he finds himself departing from the master on any fundamental question of economics, a faith, of human life.”

It was not uncommon for atheists, including Shelley, to use the words of religion when attempting to convey passionately held beliefs. And passages and expressions such as these mean that we simply can not underestimate the influence Shelley had on the socialists of this period.

“[What makes Shelley a socialist] is his singular understanding of the facts that today tyranny resolves itself into the tyranny of the possessing class over the producing class.”

In their final section, Marx and Aveling consider Shelley’s use of language, focusing on the words, “anarchy, freedom, custom, crime and property” as well as the concept of the “governing class”. Perceptively and shrewdly, they note that for Shelley the accepted meaning of certain phrases does not align with reality. Thus they touch on what came to be understood as Shelley’s famous capacity for ironic inversion. For example his deployment of the term “anarchy” to describe the then current social system and “rule of law”. For Shelley, they say, anarchy, was “God and King and Law…and let us add…Capitalism.”

On the question of “property”, Marx and Aveling reach their denouement. They begin by quoting a passage from A Philosophical View of Reform that directly anticipates Marx:

Labor, industry, economy, skill, genius, or any similar powers honourably or innocently exerted, are the foundations of one description of property. All true political institutions ought to defend every man in the exercise of his discretion with respect to property so acquired… But there is another species of property which has its foundation in usurpation, or imposture, or violence, without which, by the nature of things, immense aggregations of property could never have been accumulated.

They then paraphrase this in the language of what they call scientific socialism:

“A man has a right to anything his own labour has produced, and that he does not intend to employ for the purpose of injuring his fellows. But no man can himself acquire a considerable aggregation of property except at the expense of his fellows. He must either cheat a certain number out of the value of it, or take it by force.”

With citations from Song to the Men of England, Fragment: To the People of England, Queen Mab and a letter to Hitchener, Marx and Aveling make the case that Shelley understood,

the real economic value of private property in the means of production and distribution, whether it was in machinery, land, funds, what not. He saw that this value lay in the command, absolute, merciless, unjust, over human labour. The socialist believes that these means of production and distribution should be the property of the community. For the man or company that owns them has practically irresponsible control over the class that does not possess them.

And this, they conclude, are the “teachings of Shelley.” And as they are also the teachings of socialism, the two are one and the same thing. Thus Marx and Aveling end with the ringing words, “We claim him as a socialist.”

““We claim him as a socialist.””

According to Marx’s biographer Yvonne Kapp, Shelley’s Socialism was first published by To-day: The Journal of Scientific Socialism in 1888 (Yvonne Kapp, Eleanor Marx, p. 450). It also appeared as a pamphlet in an edition of only twenty-five copies published (presumably by the Shelley Society) for private circulation under the title Shelley and Socialism. In 1947, Leslie Preger (a young Manchester socialist who had fought in the Spanish Civil War) arranged to have it published, with an introduction by the Labour politician Frank Allaun through CWS Printing Work. The Preger edition can be found online through used book services such as AbeBooks. The version published by Preger and that which appeared in To-Day are somewhat different. The version which appears in To-Day appears to have been lightly edited and omits several selections from Shelley’s poetry that appear in the Preger edition. My assumption is that Preger reproduced the pamphlet version released by the Shelley Society. The version I have made available (see link below) is based on Preger and thus is the only complete and “authoritative” version of the speech (as delivered) available on line. You may read it online in it entirety for the first time.

In their speech, Marx and Aveling refer to a second part which they intended to deliver upon some future occasion. Either the second installment has been either lost or perhaps it was never delivered. However, Kapp tantalizingly points out that Engels in fact translated the second part into German for publication in Germany by Die Neue Zeit (Kapp p. 450). No trace of it appears to exist - a loss for us all given the intended subject matter discussed in the speech.

Frank Allaun, author of the preface to the Preger edition, offered this encapsulation of the speech: “A Marxist evaluation of the poetry of Percy Bysshe Shelley.” He concludes his preface with this sage assessment:

“Shelley, who died when his sailing boat sinking a storm in 1822, lived when the Industrial Revolution was only beginning. The owning class had not yet "dug their own graves" by driving the handloom weavers and other domestic workers from their kitchens and plots of land into the "dark satanic mills" alongside thousands of other operatives. Conditions were not ripe for the modern trade union and socialist movement. Had they been so Shelley would have been their man.”

Of the authors, George Bernard Shaw said "he (Aveling) was quite a pleasant fellow who would've gone to the stake for socialism or atheism, but with absolutely no conscience in his private life. He said seduced every woman he met and borrowed from every man. Eleanor committed suicide. Eleanor's tragedy made him infamous in Germany". Shaw added, "While Shelley needs no preface that agreeable rascal Aveling does not deserve one.”

You can read a wonderful encapsulation of Eleanor Marx and her legacy in the Jacobion, here. And you can buy Kapp’s biography of Marx here, though I strongly suggest you instead order it through your local bookseller.

Click the button to go to the speech.

The footnotes in all of the sources are antiquated and refer to out of date editions of Shelley’s poetry and prose - I will in due course provide references to more modern, available texts. Interestingly, there is no mention of the speech in any of the major Shelley biographies. Not even Kenneth Neill Cameron, a Marxist, alludes to it. Nor does Paul Foot reference it in Red Shelley. Thus, it would appear that Aveling’s and Marx’s effort to “claim Shelley as a socialist” had little effect either of the Society or upon public opinion in general. Perhaps this was predictable given the tenor of the times. As Foot observed:

Paul Foot

“In the 1840s as Engels noted, Shelley had been almost exclusively the property of the working class the Chartists had read him for what he was, a tough agitator and revolutionary. The effect of the Shelley-worship of the 1880s and 1890s was too weaken that image; to present for mass consumption a new, wet, angelic Shelley and to promote this new Shelley with all the influence and wealth of respectable academics and publishers.”

Paul Foot offers a disquieting account of the struggle during these years in chapter 7 of Red Shelley. It was a struggle which was largely won by the right and lost by the left. And it would be decades before Kenneth Neil Cameron emerged in the early 1950s to begin the lengthy and arduous process of salvaging Shelley’s left wing credentials. For generations, the Shelley that was embraced by Chartists, by Marx and Engels, would be subsumed by a tidal wave of mawkish Shelleyan “sentimentality’. Gone would be his revolutionary political ardour and in its place appeared a carefully curated selection of poetry designed to showcase only Shelley’s lyrical capabilities - his love poems.

Interestingly, to call Shelley a “love poet” can be intensely misleading. Many modern readers encountering the term “love poet” will think immediately of romantic or sexual love - and there is no doubt that Shelley wrote many poem that were almost purely romantic. However, when Shelley speaks of love, you have to look carefully at what he is saying, and what he is almost always talking about is empathy, that is the ability to imagine and understand the thoughts, perspective, and emotions of another person; to put yourself in their shoes, as it were. Shelley should therefore be thought of as the “poet of empathy” and of revolutionary love.

“Shelley should be thought of as the poet of empathy and, if anything, of revolutionary love.”

Isabel Quigley’s selection of Shelley’s Poetry: “No poet better repays cutting.”

For example, in the first part of the 20th century, Gresham Press offered a highly popular selection of poems by English poets. In the introduction to the Shelley volume, the poet and editor Alice Meynell (also a vice president of the Women Writers' Suffrage League) cheerfully announced that “ This volume leaves out all Shelley’s contentious poems.”

As recently as 1973, Kathleen Raine, in Penguin’s Poet to Poet series, omitted important poems such as Laon and Cythna - as well as most of the rest of his overtly political output. And she did so with considerable gusto, stating explicitly that she did so “without regret”. In a widely available edition of his poetry, the editor, Isabel Quigly, cheerfully notes, “No poet better repays cutting; no great poet was ever less worth reading in his entirety".

Fortunately Shelleyan scholarship has now long since passed through this dark period in his reception. The annus mirabilis in this regard was 1980, the year in which PMS Dawson published his book, Unacknowledged Legislator: Shelley and Politics, Paul Foot published Red Shelley, and Michael Scrivener published Radical Shelley: The Philosophical Anarchism and Utopian Thought of Percy Bysshe Shelley. All three owe an enormous debt to perhaps the greatest of Shelley’s politically minded biographers, the Marxist Kenneth Neill Cameron whose magisterial volume The Young Shelley: Genesis of a Radical appeared in 1958. This is a book of which one can truly be in awe.

Shelleyana!! My Father's Shelley, Part Two

Shelley had an enormous impact on me and my dad's life - though we had radically different ideas about exactly who Shelley was (which was the subject of part one of this essay). I want to explore this theme by digging into a photographic album I discovered among my father's effects after he died. It is a slim volume entitled "Shelleyana". I think we will find much to reflect upon, and Shelley may perhaps seem less remote and more immediate.

"Williams is captain, and we drive along this delightful bay in the evening wind, under the summer moon, until earth appears another world. Jane brings her guitar, and if the past and the future could be obliterated, the present would content me so well that I could say with Faust to the passing moment, "Remain thou, thou art so beautiful'."

Letter to John Gisborne, 18 June 1822. The Letters of Shelley, II 435-6

We all know what happened 16 days later; the past, the present and the future were indeed obliterated.

It is the anniversary of Shelley's death today [this article was written on July 8th 2017], and I thought the best way to observe this sad occasion was to turn again to the enormous impact Shelley on me and my dad's life - though we had radically different ideas about exactly who Shelley was. The "different" Shelleys were the subject of my essay, My Father's Shelley: A Tale of Two Shelleys." I want to further explore this theme by digging into a photographic album I discovered among my father's effects after he died. It is a slim volume entitled "Shelleyana". I think we will find much to reflect upon, and Shelley may perhaps seem less remote and more immediate.

My father's interest in Shelley must have started very early for reasons that will emerge quickly. And that fact that it did so inevitably leads my to conclude that his mother, Edith Wills, must have had something to do with it. She had an absolutely incalculable effect on his life. One of the reasons I know this is that shortly before his death I came into possession of hundreds of letters that he had written to her. She appears to have kept almost all of them. There is a generous sprinkling of those she wrote to him, but he does not appear to have been as concerned for posterity as she was.

My father was born in 1916 in Montreal, Canada. Very early in life he exhibited an aptitude for, and an interest in, the arts. This came from his mother, and not his father. He assiduously studied music and was good enough that he was in a position at one point to chose a career as a professional pianist. But he abandoned this for the stage. In his late teens he was active in the Montreal theatrical community. Then he did something truly extraordinary. In 1936, at age 18 he boarded a ocean liner and sailed for England to pursue an acting career.

While he did not appear to have set the acting word on fire, he did seem to progress his career until the Second World War ruined his dreams as it did those of almost everyone else on the planet.

The cover of my father's Shelley "scrap book".

While in England he also took the time to pursue a passion of his: Percy Bysshe Shelley. I know this because I have an unusual little scrap book which I found on his shelf with the rest of his Shelley materials. It is a bit shabby now, but he appears to have spent considerable effort to put it together - beginning in 1937.

"Shelleyana"

Now the term "Shelleyana" is an interesting term in and of itself, and I have been unable to find any "official" definition for it. It is used to refer to collections of materials that pertain to Shelley and his circle. It is clearly a coined term and I can think of no other example of it. There is an affectionate overtone; it strikes one as diminutive. It is even a little cloying. All of which is entirely in keeping with the manner in which Shelley was viewed by a large segment of the literate intelligentsia in the 19th century. I wrote about this in my article, "Shelley in the 21st Century."

Many people who held Shelley in high esteem had collections of "Shelleyana". These might be relics, or they might be first editions, or they might be rare or unusual books about him or those he was close to. For example, here is an article from the New York Times in 1922 extolling a particular collection of Shelleyana which was available to the public on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of his death.

My father always referred to his collection of books on Shelley as his "Shelleyana". And as suits the reverential, almost hagiographic overtone, which the term connotes, his scrap book begins with not one, but THREE portraits of the poet - each accorded its own page.

Amelia Curran's 1819 portrait of Shelley which hangs in the National Portrait Gallery

This is the most famous, even iconic, of the portraits. Shelley sat for Curran in Rome on May 7 and 8 in 1819. Curran was known to Shelley and Mary and they had last encountered her in Godwin's home in 1818. Crucially, this painting was NOT finished in his life time, and must be considered to be an extremely unreliable likeness. Shelley's biographer, James Bieri notes, "It has become the misleading image by which so many have misperceived Shelley." We know that neither Mary nor Shelley liked it - nor did his friends. The history of this painting and its effect on the way in which Shelley came to be regarded can not be underestimated, but this is not the time and place for such a discussion. Suffice to say that it played directly into the hands of those Victorians who preferred to imagine Shelley as a child-like, almost androgynous being - this is the "castrated" Shelley (in Engles' famous phrase). The man in this painting is NOT my Shelley - but it was most decidedly my father's Shelley.

Here is the second:

A crayon portrait based on the painting by George Clint

Well, what can you say? Here Shelley has lost almost all of his masculine characteristics and the ethereal being the Victorians (and my father) so came to adore is born. We are getting very close Mathew Arnold's vision of Shelley as "a beautiful and ineffectual angel, beating in the void his luminous wings in vain". Clint's portrait was painted in 1829 years after his death, and is known to be a composite of Curran's painting and a sketch by Shelley's friend, Edward Williams.

Sketch by Edward Ellerker Williams, Pisa, 27 November 1821

Curran's painting was repainted several times and each time, Shelley become less recognizable, more child-like, more androgynous, more ethereal. I believe these images of Shelley played a central role in the re-invention and distortion of his reputation. For example, here is Francis Thompson (one of his Victorian idolators) writing in 1889:

“Enchanted child, born into a world unchildlike; spoiled darling of Nature, playmate of her elemental daughters; "pard-like spirit, beautiful and swift," laired amidst the burning fastnesses of his own fervid mind; bold foot along the verges of precipitous dream; light leaper from crag to crag of inaccessible fancies; towering Genius, whose soul rose like a ladder between heaven and earth with the angels of song ascending and descending it;--he is shrunken into the little vessel of death, and sealed with the unshatterable seal of doom, and cast down deep below the rolling tides of Time.” - Francis Thompson, "Shelley", 1889

The story of the incalculable damage that these stylized images wrought, divorced as they were from reality, has yet to be properly told. But I think it is fair to say that had no portraits of Shelley ever existed, we might see him in a very different light today. I think that portraits like these fed a particular vision of Shelley that my father fed off. Looking into the eyes of these three Shelleys, it is difficult to see the revolutionary, the philosophical anarchist, the atheist that he was.

Postcard purchased at the Bodleian by my father, July 1937

On the next page we find, not unsurprisingly, a postcard my dad purchased in July, 1937 in Oxford at the Bodleian. It displays certain Shelley "relics". These are: (1) the copy of Sophocles allegedly taken from Shelley's hand after his body washed ashore; (2) locks of Shelley's and Mary's hair; (3) a portrait of him as a boy; (4) his baby's rattle; and (5) his pocket watch and seals.

The idea that Shelley was found with that book in his hand is a story we owe to one of the most notorious liars in history, Edward Trelawny who for his entire life trafficked in stories derived from his association with Shelley and Byron - two men, both dead, who could not contradict his lies. There are certain element of his biography of Shelley which we can take at face value, but they are few and far between. But stories like that, when the become "relics" and part of "Shelleyana" feed myths. My dad was always fond of Trelawny - and Trelawny did my father the ultimate disfavour of serving up a vision of Shelley that was almost completely divorced from reality.

Onslow Ford's Shelley Memorial, University College, Oxford. Commissioned in 1891.

Next up, entirely predictably, is one of the great abominations in the canon of Shelleyana - the famous (or infamous) Shelley Memorial at University College, Oxford. The history of this hardly bears repeating. It was so routinely disfigured and disrespected by young Oxford students that today it is actually encased in a cage. It was Shelley's daughter-in-law who perpetrated this imaginative, shambolic disaster. Paul Foot absolutely shreds this statue in his speech, "The Revolutionary Shelley"

Not content with this, she went further and commissioned Henry Weeks to reinvent Shelley as Christ and Mary as, well, another Mary. The resulting statute was, according to my father, refused by Westminister on the grounds of his atheism - if this anecdote is in any way true, I rather doubt his atheism had anything to do with it; more likely it was the monstrously poor taste in which the statue was executed. You be the judge:

Henry Weeks, Shelley Memorial, Christchurch Priory, Bournemouth, England

Shelley's birthplace, "Field Place", Horsham, Sussex.

It is now that the scrapbook becomes more interesting, for it becomes clear that my 19 year old father was engaged on a sort of pilgrimage, following in the footsteps of Shelley. The preceding pages feature postcards clearly acquired on a visit to Oxford in July of 1937; a visit clearly focused almost exclusively on Shelley. However, the previous year, and almost immediately upon his arrival in England, he traveled to Shelley's birthplace where he took a sequence of poorly composed but magical photographs:

There are thousands of beautiful pictures of Field Place; these are awful. But that is not the point. These photographs have a haunting, poignant, other-worldly quality. They were taken by an 18 year old boy who was enthralled by his hero, Shelley. And they take us back in time almost a century. He kept a very detailed diary of those years, and his thoughts and reflections in this pilgrimage are memorable and touching.

The graves of Mary, Mary Wollestonecraft, William Godwin, Percy Florence Shelley and the latter's wife, Jane Shelley

Dad also visited the graves of Mary, Mary Wollestonecraft, William Godwin, Percy Florence Shelley and the latter's wife, Jane Shelley. As he notes, "They are all in one plot of ground (barely sufficient for five people to die down)....One stone does for all." Interestingly, Mary had refused Trelawny's offer of the plot he had reserved for himself beside Shelley's grave in Rome. I have always found that curious, though none of Shelley's biographers offer any thoughts on this. Had she not refused, it would have been she and not Trelawny who is buried beside Shelley. This is, I think, a great loss; for more than one reason.

The home in Marlow in 1937

Prior to visiting Oxford in July of 1937, my father also dropped by Marlow to visit Shelley's home in that location. The pictures are somewhat clearer and he records the inscription above the dwelling which includes the line "...and was here visited by Lord Byron."

Lechlade, Gloucestershire, 1936

One of my father's favourite poems by Shelley was "Lechlade:A Summer-Evening Churchyard" so, of course he went there in 1936. In a chemist shop owned by a man named Davis, he was informed that according to local legend, Shelley had strolled through a particular path in the town composing the poem. The top photograph shows this path, the bottom, the neighbouring cathedral.

We now come to one of the more significant fabrications of literary history. The cremation of Shelley. Here is the painting by Louis Edward Fournier;

Louis Edward Fournier, "The Burning of Shelley", 1889.

It is not for me to debunk the many myths created by one of history's great liars, Edward John Trelawny (Bieri does an excellent job in his biography of Shelley). Shelley was indeed cremated by the bay of Lerici. The body had washed ashore after 10 days rotting in the ocean. It was thrown into a shallow grave and covered with lime. It was only over a month later that permission was finally received to exhume the body and cremate it - and what they found was horrific - the body was "badly mutilated, decomposed and destroyed." Mary was NOT at the burning and Byron refused to witness it himself. This painting, like so many of the other signal components of the Shelley myth, was hagiographic in tone and divorced from reality. But to an impressionable 19 year old Canadian on a pilgrimage in the footsteps of Shelley, it was as good as gold.

Upper right, Keats' tomb. Lower left, Trelawny, lower right, Shelley, Photographs 1950

The Second World War then stole almost 10 years from my father's life, as it did for so many millions more. He was lucky to be demobilized quickly and lucky again to find employment quickly. He became a journalist and rose very quickly to become the most famous Canadian broadcaster of his era. I will tell THIS story elsewhere. In 1950 he secured an extraordinary assignment. Tour the world and send stories back to Canadians eager to learn about strange an exotic locales. One of the places he went was Rome and it will surprise no one reading this that he made a beeline to the Protestant Cemetery and Shelley's grave.

The photographs are poorly composed and either under or over exposed. But again, they have an intensity, a nostalgia and a haunting quality which are undeniable. So many things strike me. why did my father have his picture taken at Keats' grave and not Shelley's? He had very little time for Keats. Why only a picture of the tombstone itself? I have been in the Cemetery. It is an extraordinary lace and it must have been even more extraordinary in 1950 when the world was literally bereft of tourists. The photograph of Shelley's grave, in many formats, graced our home through out my life. My father curiously never had it properly framed or preserved - and the negatives are long lost. But I treasure these images, the more so for their faded character, there soiled nature and their shop-worn corners.

Larry Henderson at Casa Magni, Lerici, Italy, September 1986

My father was a thorough man, and in 1986, as a vigorous 70 year old he made his way to the Bay of Lerici to visit the site of Shelley's death and his last domicile, the Casa Magni. Anna Mercer has made her own pilgrimage to Lerici, and her wonderful story, "In the Footsteps of the Shelleys" can be found here. He can be seen here, in one of his very typical poses, in front of Shelley's last home.

From his first pilgrimage in 1936, to his last 50 years later in 1986, my father was devoted to the man and the poet he perceived Shelley to be. While we could never find any common ground in our mutual appreciations for Shelley, which I wrote about in "My Father's Shelley: A Tale of Two Shelleys", I have come to realize that in his passion for Shelley, I am my father's son (and perhaps my grandmother's grandson!). I do not know if my father's and grandmother's love for this man will descend to another generation of Hendersons, but if it does not and if it ends here, it has be a truly memorable run. And were Shelley alive to have witnessed all this, as a man who believed that the world could indeed be changed one person at a time, I am hope he would be well and truly satisfied.

THE WIND has swept from the wide atmosphere

Each vapor that obscured the sunset’s ray;

And pallid Evening twines its beaming hair

In duskier braids around the languid eyes of Day.

Silence and Twilight, unbeloved of men,

Creep hand in hand from yon obscurest glen.

They breathe their spells toward the departing day,

Encompassing the earth, air, stars, and sea;

Light, sound, and motion own the potent sway,

Responding to the charm with its own mystery.

The winds are still, or the dry church-tower grass

Knows not their gentle motions as they pass.

Thou too, aerial pile, whose pinnacles

Point from one shrine like pyramids of fire,

Obeyest in silence their sweet solemn spells,

Clothing in hues of heaven thy dim and distant spire,

Around whose lessening and invisible height

Gather among the stars the clouds of night.

The dead are sleeping in their sepulchres;

And, mouldering as they sleep, a thrilling sound,

Half sense, half thought, among the darkness stirs,

Breathed from their wormy beds all living things around;

And, mingling with the still night and mute sky,

Its awful hush is felt inaudibly.

Thus solemnized and softened, death is mild

And terrorless as this serenest night;

Here could I hope, like some inquiring child

Sporting on graves, that death did hide from human sight

Sweet secrets, or beside its breathless sleep

That loveliest dreams perpetual watch did keep.

Percy Bysshe Shelley, drowned at sea, 8 July 1822.

"Death is mild and terrrorless as this serenest night."

My Father's Shelley; a Tale of Two Shelleys

My father’s Shelley, as I VERY quickly discovered, was very different from mine. He loved the lyric poet. He loved the Victorian version. He loved Mary’s sanitized version. In a weird way he bought into Mathew Arnold's caricature of Shelley (“a beautiful and ineffectual angel, beating his wings in a luminous void in vain.”) – and loved him the more for it. He hated the idea that Shelley was a revolutionary.

When I was very little, my father, dissatisfied with the state of my education, decided that he would offer Sunday evening lectures in his library. And so each Sunday, at exactly the time Bonanza was on, my brother and I would be herded into the library, moaning and complaining. A chalk board was produced. And the entire history of the Greek and Roman world played out, slowly, labouriously, on that chalk board over the ensuing years...or at least it seemed like years.

In addition to ancient history, recent poetry was assigned for memorization. When I say recent, I mean poetry from the 18th and 19th centuries. To this day, I have a little volume of around 20 poems that he gave to me – all specially selected. It was quite a cross-section.

We would actually be QUIZZED on poetry and history!! As if school wasn't bad enough. There were, however, incentives. I think we got 50 cents for every poem we could successfully recite. I recently found a little postcard that he sent home from one of his travels. It ended with a gentle admonition to make sure I had something new memorized for him upon his return. I discovered one of the quizzes years after his death. Have a look...how well would a 10-12 year old do today? -- how well would a university student do?!

Now as much as this grated on me when i was young, it did engender in me a love for classical culture and poetry. It also led to some amusing disagreements over the years. My father was deeply aggrieved, for example, that I failed to enshrine Pope's translation of the Iliad as the only translation worth having. On one visit to our home, he stood at my bookshelves gazing with open dismay on my collection of translations of the Iliad - at that time well over a dozen. He thought this was perverse. My wife ventured the thought that it must be wonderful to see a seed that he had planted grow to such fruition - but he was having none of it; I had sinned against Pope, the God of the Iliad. Weeks later, the issue was still occupying his thoughts. At a lunch with my brother, agitated, he put down his knife and fork and asked my brother what was wrong with me. Alexander Pope had been good enough for him (and by extension the entire world), why did I feel the need to venture afield and embrace these other pretenders: "Ross, what is wrong with Alexander Pope?" he lamented in his highly theatrical voice. What indeed?!

Later in life he also came down firmly on the side of the Greeks. Once, my brother gave him a book on the emperor Diocletian. Dad promptly returned the book unread, bitterly remarking upon Ross' and my putative adherence to Roman civilization - "The Romans," he remarked dismissively, "were nothing but bully-boys." But I digress.

As I grew up, like most boys, I actively sought out things to like and do that distanced me from my father. For example, I spent most of my high school years studying maths – a subject matter as alien to my father as any subject on earth. Then I went to University to be a geologist. Disaster. I finally dropped out and worked for a year or so, only to return to University where I ended up studying English Literature. I am not sure what it was that led me to Shelley. But something did…. perhaps the awful shadow of some unseen power. I went deeper and deeper: first an undergraduate thesis and then an MA thesis (undertaken under the supervision of that great Shelley scholar, Milton Wilson). I even started out on a PhD before I came to my senses.

Anyway, to the point. In those days, when one’s thesis was completed, they would bind up a couple of copies for you. Now by this point in my life, I have to confess, somewhat ruefully, that my father and I were barely on speaking terms. Nonetheless, like most young men, I still craved his approval. So, thesis in hand, I traveled to the family homestead to see my parents. Burning a hole in my briefcase was a copy of my thesis: “Prometheus Unbound and the Problem of Opposites.” (Hopefully soon to be published in this space!)

He was in his library. After spending sometime in the kitchen with my mum, I screwed up my nerve and knocked on the door. He called me in. As always, we had to stand at the door waiting for him to finish whatever thought it was that he was in the midst of jotting down. He was ALWAYS writing, furiously, on a clipboard. Finally, after what seemed an eternity, he looked up and said hello.

I explained what I was doing. I presented him with the thesis. And then something truly surreal happened; something that seared itself into my memory. Without really looking at it, he smiled absently, congratulated me and turned to walk toward his library shelves with my thesis. He casually remarked over his shoulder, “Thank you, Gra, I shall put it with the rest of my Shelleyana.”

Time slowed to a stop. I remember struggling to understand what that could mean. But my gaze followed his hands, up, up, up to the higher shelves. And there it was…sweet mother of god…maybe 10 linear FEET of books on Shelley.

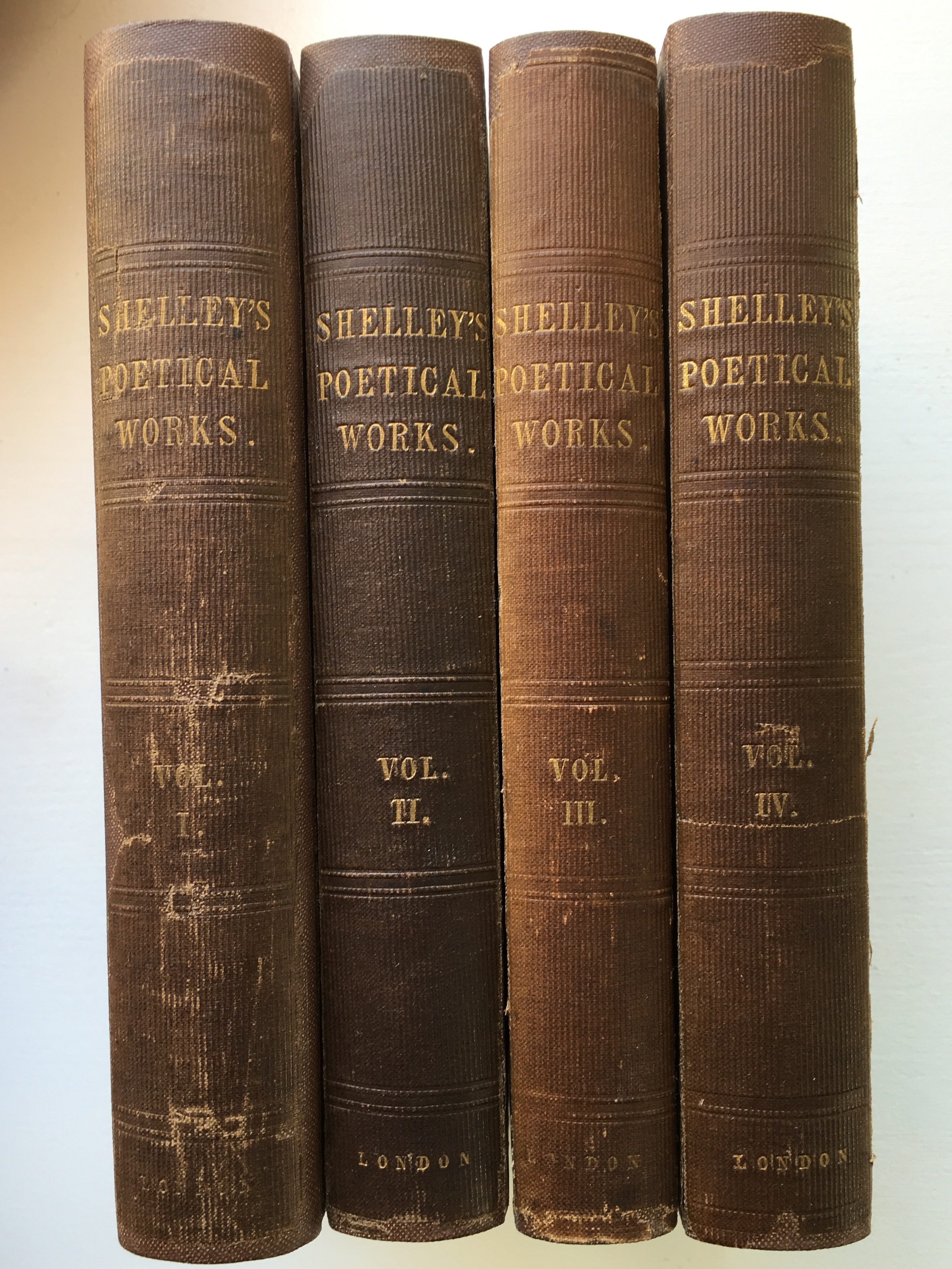

Approximately 1/3 of my father's "Shelleyana". Most of these books are first editions.

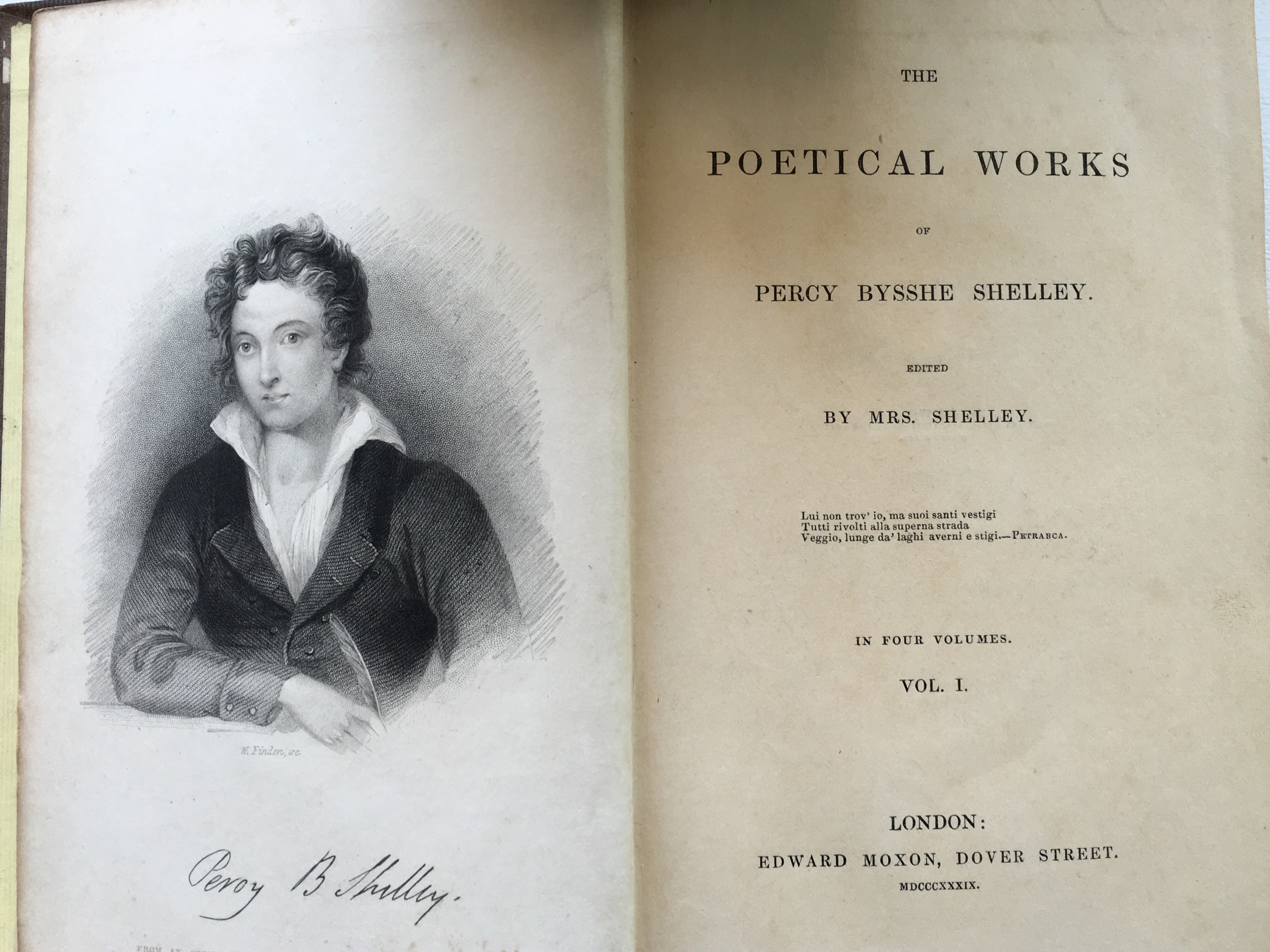

I did not realize at the time, but this collection also happened to include a first edition of “The Revolt of Islam” and the four volume 1839 Collected Works that Mary put out. I kid you not. In fact, it turned out that almost everything up there on those shelves was a first edition of some sort. It was like an Aladdin’s cave specially built for Shelley scholars. People like ME…people like…oh my god…my DAD!! Click on the image to see the slide show:

Inscription to my brother in Hutchinson's Collected Works of Shelley

Now in retrospect, none of this should have really been a big surprise. For starters, my brother’s middle name is Shelley (I am not sure he appreciated the choice as a boy). Dad had given him a copy Hutchinson's "The Complete Poetical Works of Shelley" (a gorgeous single volume, with gilt edged paper and blue calf skin binding) in 1956...AT AGE ONE!! It bore an inscription to my brother: 'The secret strength of things / Which governs thought, and to the infinite dome / Of heaven is as a law, inhabits thee!.'

My markups to Hutchinson's "Poetical Works of Shelley" -- given to my brother at age 1.

I knew this because it was this volume I had used throughout my entire course of Shelley studies.

And then, finally there was that other piece of evidence: there had been a Shelley poem in that little black volume I was given when I was around 10. As it turned out, Shelley was my father’s favourite poet. The man I barely spoke to, the man I had spent most of my life distancing myself from, was -- just like me -- devoted to Percy Bysshe Shelley. This was a sobering and disquieting revelation. As I reflect back on this, what I wonder is this: was it THAT poem? Was it Shelley's poem, the one he gave me to memorize, that planted the seed which flowered so many years later?

Well, before we get to that, I am afraid to say that it actually gets weirder. As I stood there, my jaw working, no sounds coming out of my mouth, he turned back to me and asked me what I meant by the “Problem of Opposites.” He asked if this was a reference to Jung, by any chance. By this time I knew where this is going -- there was an inevitability to it; there was an inexorable fate at work. He then gestured vaguely across the room at another shelf load of books. Yes, that’s right: The Complete Works of C.G. Jung. He asked if I would like to borrow any of them if I was continuing my studies on Jung and Shelley.

Because, of COURSE, that is EXACTLY what I had spent the better part of four years doing - applying Jungian theory to the study of Shelley's poetry.

I should point out that my approach to Shelley was so arcane and unique that my thesis supervisor, Milton Wilson, had a hard time drumming up professors to quiz me. It was niche to say the least. Yet somehow I had stumbled onto a course of study that duplicated two of my father's keenest interests.

Retreating from the library in some bemusement, I walked into the kitchen and my poor mother looked at me in dismay. “You look awful,” she said, “You look like you just saw a ghost. What happened in there?” Good question.

I can laugh about all of this now. But then? Not so much. I was young and desperate to be different.

As I sat at the kitchen table trying to sort through my emotions, I thought, “Well, at least, I now have something to talk to him about”. And so a desultory communication began. But this too soon turned into almost open warfare. My father’s Shelley, as I VERY quickly discovered, was very different from mine. He loved the lyric poet. He loved the Victorian version. He loved Mary’s sanitized version. In a weird way he bought into Mathew Arnold's caricature of Shelley (“a beautiful and ineffectual angel, beating his wings in a luminous void in vain.”) – and loved him the more for it. He hated the idea that Shelley was a revolutionary. I have an article coming on the truly remarkable evolution of Shelley's reputation - it is unlike almost another poet in history. Well, my father loved the Victorian version of Shelley, the version which led Engles to remark:

"Shelley, the genius, the prophet, finds most of [his] readers in the proletariat; the bourgeouise own the castrated editions, the family editions cut down in accordance with the hypocritical morality of today”

I once gave him a copy of Foot’s “The Red Shelley”. This was not well received. He hated the idea that Shelley was anything but the child-like construct of Francis Thompson:

“Enchanted child, born into a world unchildlike; spoiled darling of Nature, playmate of her elemental daughters; "pard-like spirit, beautiful and swift," laired amidst the burning fastnesses of his own fervid mind; bold foot along the verges of precipitous dream; light leaper from crag to crag of inaccessible fancies; towering Genius, whose soul rose like a ladder between heaven and earth with the angels of song ascending and descending it;--he is shrunken into the little vessel of death, and sealed with the unshatterable seal of doom, and cast down deep below the rolling tides of Time.”

We had heated arguments about this.

My father's marginalia in Santayana's short monograph on Shelley. "not a communist." Almost every statement Santayana makes on this page is completely incorrect,

As recently as a few months back, I was browsing through his library (he has been dead these past 9 years, but I have kept most of the library together – it is a reflection of his vast and complex mind). I pulled a slim volume from the Shelley shelves; one I had not looked at before. It was George Santayana’s short monograph on Shelley, "Shelley: Or the Poetic Value of Revolutionary Principles". My father was a fierce marker-up of books – another thing he seems to have bequeathed to me. I like flipping through his books to see what he underlined and what his comments were. I often get into arguments with his comments, writing my own in beside his. Anyway, half way through the essay, in one of the margins, were the words , “NOT A COMMUNIST” in a bold, firm, triumphant hand.

Now, my father was a big time anti-communist; he spent most of his life fighting the cold war and then refighting it after it was over. One of his great fears was that Shelley was some sort of communist! And of course, this EXACTLY what the communists thought he was! Marx:

"The real difference between Byron and Shelley is this: those who understand and love them rejoice that Byron died at 36, because if he had lived he would have become a reactionary bourgeois; they grieve that Shelley died at 29, because he was essentially a revolutionist and he would always have been one of the advanced guard of socialism."

But there, for my father, in the calming words of the great George Santayana, was solace and respite: no, Shelley was NOT a communist. Phew.

There can never be a resolution between these two visions of Shelley. My father's Shelley was a Shelley built on false foundations, willful misreadings and wishful thinking. He, and others like him, created a mythical version, so far removed from the historical Shelley that it is scarcely believable. The way in which this awful perversion of history took place is concisely covered in Michael Gamer's article, “Shelley Incinerated.” (The Wordsworth Circle 39.1/2 (2008): 23-26.) I intend to canvas the issues more fully at a future date.

It saddens me that our two Shelleys were separated by an unbridgeable chasm. But I have to always remember that my Shelley could never have come to life had not my father, in a very different time and place, conceived his own Shelley, and fallen in love with him and endeavoured to convey that passion to his children.

But how about that poem? The poem that may have planted the seed of which I was utterly unaware. What exactly was the Shelley poem in that little binder he had given to me at age 9 or 10? I know it by heart to this very day. It was this:.

Arethusa arose

From her couch of snows

In the Acroceraunian mountains,--

From cloud and from crag,

With many a jag,

Shepherding her bright fountains.

She leapt down the rocks,

With her rainbow locks

Streaming among the streams;--

Her steps paved with green

The downward ravine

Which slopes to the western gleams;

And gliding and springing

She went, ever singing,

In murmurs as soft as sleep;

The Earth seemed to love her,

And Heaven smiled above her,

As she lingered towards the deep.

II.

Then Alpheus bold,

On his glacier cold,

With his trident the mountains strook;

And opened a chasm

In the rocks—with the spasm

All Erymanthus shook.

And the black south wind

It unsealed behind

The urns of the silent snow,

And earthquake and thunder

Did rend in sunder

The bars of the springs below.

And the beard and the hair

Of the River-god were

Seen through the torrent’s sweep,

As he followed the light

Of the fleet nymph’s flight

To the brink of the Dorian deep.

III.

'Oh, save me! Oh, guide me!

And bid the deep hide me,

For he grasps me now by the hair!'

The loud Ocean heard,

To its blue depth stirred,

And divided at her prayer;

And under the water

The Earth’s white daughter

Fled like a sunny beam;

Behind her descended

Her billows, unblended

With the brackish Dorian stream:—

Like a gloomy stain

On the emerald main

Alpheus rushed behind,--

As an eagle pursuing

A dove to its ruin

Down the streams of the cloudy wind.

IV.

Under the bowers

Where the Ocean Powers

Sit on their pearled thrones;

Through the coral woods

Of the weltering floods,

Over heaps of unvalued stones;

Through the dim beams

Which amid the streams

Weave a network of coloured light;

And under the caves,

Where the shadowy waves

Are as green as the forest’s night:--

Outspeeding the shark,

And the sword-fish dark,

Under the Ocean’s foam,

And up through the rifts

Of the mountain clifts

They passed to their Dorian home.

V.

And now from their fountains

In Enna’s mountains,

Down one vale where the morning basks,

Like friends once parted

Grown single-hearted,

They ply their watery tasks.

At sunrise they leap

From their cradles steep

In the cave of the shelving hill;

At noontide they flow

Through the woods below

And the meadows of asphodel;

And at night they sleep

In the rocking deep

Beneath the Ortygian shore;--

Like spirits that lie

In the azure sky

When they love but live no more.

Well chosen, Dad, well chosen; and thank you for this great gift (thanks also for not giving ME the middle name, Shelley!).

- Aeschylus

- Amelia Curran

- Anna Mercer

- Arethusa

- Arielle Cottingham

- Atheism

- Byron

- Charles I

- Chartism

- Cian Duffy

- Claire Clairmont

- Coleridge

- Defense of Poetry

- Diderot

- Douglas Booth

- Earl Wasserman

- Edward Aveling

- Edward Silsbee

- Edward Trelawny

- Edward Williams

- England in 1819

- Engles

- Francis Thompson

- Frank Allaun

- Frankenstein

- Friedrich Engels

- George Bernard Shaw

- Gerald Hogle

- Harold Bloom

- Henry Salt

- Honora Becker

- Hotel de Villes de Londres

- Humanism

- James Bieri

- Jeremy Corbyn

- Karl Marx

- Kathleen Raine

- Keats-Shelley Association

- Kenneth Graham

- Kenneth Neill Cameron

- La Spezia

- Larry Henderson

- Leslie Preger

- Lucretius

- Lynn Shepherd

- Mark Summers

- Martin Priestman

- Marx

- Marxism

- Mary Shelley

- Mary Sherwood

- Mask of Anarchy

- Michael Demson

- Michael Gamer

- Michael O'Neill

- Michael Scrivener

- Milton Wilson

- Mont Blanc

- Neccessity of Atheism

- Nora Crook

- Ode to the West Wind

- Ozymandias

- Paul Foot

- Paul Stephens

- Pauline Newman

- Percy Shelley

- Peter Bell the Third

- Peterloo

- Philanthropist

- philanthropos tropos

- PMS Dawson

- Political Philosophy

- Prince Athanese

- Prometheus Unbound

- Queen Mab

- Richard Holmes

- romantic poetry

- Ross Wilson

- Sandy Grant

- Sara Coleridge

- Sarah Trimmer

- Scientific Socialism

- Shelleyana

- Skepticism

- Socialism

- Song to the Men of England

- Stopford Brooke

- Tess Martin

- The Cenci

- The Mask of Anarchy

- The Red Shelley

- Timothy Webb

- Tom Mole

- Triumph of Life

- Victorian Morality

- Villa Diodati

- William Godwin

- William Michael Rossetti

- Wordsworth

- Yvonne Kapp