Atheist, Lover of Humanity, Democrat

PERCY BYSSHE SHELLEY

The Shelley Conference - London, 15-16 September 2017

On Friday and Saturday the 15th and 16th of September, in London, the Centre for Eighteenth Century Studies at University of York, is presenting a two day conference that celebrates the writings of Percy Bysshe Shelley and Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley. I will be speaking at this conference on the topic of "Romantic Resistance". My presentation will demonstrate how Shelley’s politics, his philosophical skepticism and his theory of the imagination combine to offer some potent solutions for the troubles of the early 21st Century. Given recent events, it is time that we cast a fresh eye on romantic, specifically Shelleyan, theories of resistance.

On Friday and Saturday the 15th and 16th of September, in London, the Centre for Eighteenth Century Studies at University of York, is presenting a two day conference that celebrates the writings of Percy Bysshe Shelley and Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley. The event is organized by two brilliant young young Romantics scholars: Anna Mercer and Harrie Neal.

I will be speaking at this conference.

Keynote speakers include some of the very top people in this field: Professor Nora Crook, Michael Neill and Kelvin Everest. But there are also a host of panel discussions that look excellent. I strongly recommend this conference to anyone who can make it. The price is right and many of the topics are mouthwatering.

Some of the names that will be familiar to my readers include: Mark Summers who will talk about "Reclaiming Shelley's Radical Republicanism"; Anna Mercer on the extent to which Percy and Mary collaborated; Jacqueline Mulhallen on "1817 - a Philosophical Year for Shelley"; and Lynn Shepherd on "Fictionalizing the Shelleys".

As for me, my topic will be the subject of "Romantic Resistance." Shelley's writing affords modern political activists a veritable treasure trove of ideas and, as one of my readers put it, "Words of Power". As we contemplate a world in which wealth is concentrated in ever fewer hands, a world in which superstition and religion are increasing their pernicious influence, a world in which tyrants are proliferating, we must see that our world is very much Shelley's. We have need of his guidance. He was one of the greatest political thinkers of any age.

The event takes place at the Institute for English Studies, Senate House, Malet Street, London Greater London WC1E 7HU (near to the British Museum).

Paul Foot understood this. He persistently and passionately promoted Shelley's ideas to a generation of leftists whom he believed had lost their intellectual vigor as well as their connection to the problems of everyday people.

Paul Foot

He offered this reason for restoring Shelley to prominence: modern activists need, he said in his famous speech to the 1981 London Marxism Conference,

"...a language which has some bite and zest and enthusiasm. That’s what we have to do and that’s why I think reading great revolutionary poets like Shelley is fundamentally important. It is filled with all kinds of images, all kinds of similes and metaphors - ways of saying things, different ways of saying things. The great masters of language really understood language and could use it like great musicians use the piano. These are things we need to soak up. Particularly when those great masters of language are in line with our politics."

But I think there is more, much more, than just language. Timothy Webb once said of Shelley that “politics was probably the dominating concern of his life.” My presentation will demonstrate how Shelley’s politics, his philosophical skepticism and his theory of the imagination combine to offer some potent solutions for the troubles of the early 21st Century. Given recent events, it is time that we cast a fresh eye on romantic, specifically Shelleyan, theories of resistance.

When Shelley declared in Chamonix that he was a “lover of humanity, a democrat and an atheist” he did so knowing his words would be widely read. The “Chamonix Declaration”, as I refer to it, was a more revolutionary statement than has commonly been assumed. I will offer a new interpretation of what Shelley meant by these words and the radical programme he proposed to upend the political and religious status quo.

Mont Blanc

To do this I will reopen the question of Shelley’s philosophical skepticism and the role it played in his theory of revolution. For Shelley skepticismwas a critically important tool to undermine authority and attack truth claims. In an age of “alternative facts” and “fake news” the value of skepticism as a discipline and approach to tyranny is all too evident. Mere skepticism was not and still is not, enough, however, to effect permanent political change.

I will argue that Shelley therefore evolved a theory of the imagination, at a time almost exactly contemporaneous to the Chamonix Declaration, to provide a mechanism for permanent revolutionary change; the type of change that would avoid the backsliding into chaos and tyranny he witnessed in the aftermath of the French Revolution.

Shelley has answers that remain as relevant today as they were in his time; just how we communicate those answers to the general public will also be discussed. Shelley famously wrote, "Mont Blanc yet gleams on high: the power is there," he did not mean for us to think the power lay outside us. It is actually within us all. We have the power to change the world. But we have to act. Paul Foot understood this well when he said:

Of all the things about Shelley that really inspired people since his death, the thing that matters above all is his enthusiasm for the idea that the world can be changed. It shapes all his poetry. And when you come to read Ode to the West Wind where he writes about the “pestilence stricken multitudes” and the leaves being blown by the wind; then you understand that he sees the leaves as multitudes of people stricken by a pestilence. You begin to see his ideas, his enthusiasm and his love of life. He believed in life and he really felt that life is what mattered. That life could and should be better than it is. Could be better and should be better. Could and should be changed. That was the thing he believed in most of all.

Please join me and others in London on September 14-15 for a wonderful excursion into the brilliant minds of Percy and Mary Shelley.

Shelley Square in Viareggio, Italy.

Shelley Storms the Fashion World with Mask of Anarchy

In what is surely one of the most unusual but at the same time coolest uses of Shelley's poetry, English fashion designer John Alexander Skelton deployed Shelley's Mask of Anarchy in his recent runway show. The circumstances are quite extraordinary.

In what is surely one of the most unusual but at the same time coolest uses of Shelley's poetry, English fashion designer John Alexander Skelton deployed Shelley's Mask of Anarchy in his recent runway show. The circumstances are quite extraordinary.

First, Skelton's entire clothing line was inspired by, and I am not making this up, the Peterloo Massacre. According to Rebecca Gonsalves,

"Skelton was inspired by the Peterloo Massacre of 1918 [sic], which saw armed cavalry charge into a peaceful pro-democracy protest in Manchester, killing many and injuring hundreds, and in turn inspiring Shelley’s controversial poem."

While Gonsalves has the date of Peterloo wrong (it took place in 1819) she gets the rest absolutely right.

Skelton has to be one of the first clothing designers in history whose clothing line was inspired by a bloody massacre. This might strike many as unusual, but I think it is actually quite an important example of art interfacing with politics and political protest – in a manner Shelley would have whole-heartedly approved.

Skelton, hailing from York, had recently become aware of the events at Peterloo. According to Gonsalves, he was appalled not only by the loss of life and the carnage, but also the fact that two hundred years later, this massacre has not been properly memorialized by the English authorities. If anything it has been swept under the carpet.

From Michael Demson's Masks of Anarchy which you can buy here.

I have written at length about Peterloo in my review of Michael Demon’s graphic novel, “Masks of Anarchy”. It was also referred to by Mark Summers, in his article which I republished here. Briefly the facts are as follows: On the morning of 16 August 1818, a peaceful assembly of some sixty thousand English men, women and children began to gather in what is now St. Peter’s Square in Manchester (hence the name the massacre was popularly given: Peterloo). They did so quietly and with discipline. The protest was organized by the Manchester Patriotic Union and was to feature the famed orator Henry Hunt. Here is Demson's depiction of the event:

Hunt was to speak from a simple platform in front of what is now the Gmex Center. The crowd brought homemade banners that proclaimed REFORM, UNIVERSAL SUFFRAGE, EQUAL REPRESENTATION and LOVE. But before the speeches could begin, local magistrates ordered the local militia (known as ‘yeomanry”) to break up the meeting. This was done with extraordinary violence. As many as 12 protestors died and over 500 were wounded.

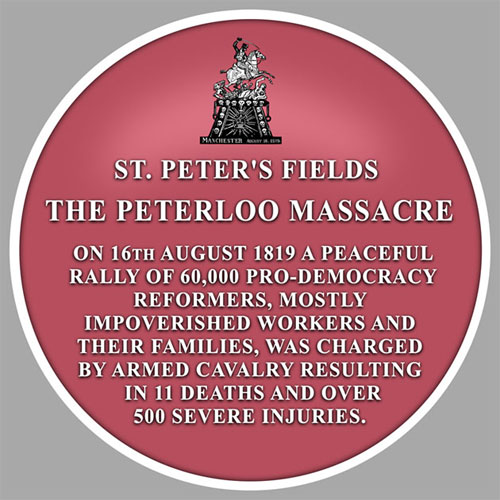

In the aftermath, journalists attempting to cover the massacre were arrested and news of the event suppressed. The businessman John Edwards Taylor was so shocked by what had happened that he went on to help set up the Guardian newspaper to ensure that the people would have a voice. Today the massacre still lacks an appropriate memorial despite decades of demand. For years, the event was commemorated only by a blue plaque which described the massacre as follows:

“The site of St Peters Fields where on 16th August 1819 Henry Hunt, radical orator addressed an assembly of about 60,000 people. Their subsequent dispersal by the military is remembered as “Peterloo”.

That the term “dispersal” is used to describe what was a massacre is an unconscionable euphemism. It was only in 2007 that the following plaque replaced it:

You can read about the Peterloo Memorial Campaign here.

According to Michael Scrivener, “the response of the radical leadership to Peterloo was surprisingly timid…the leaders must have been more alarmed than inspired by the revolutionary situation”. Hunt, for example, called for passive resistance in a variety of forms (such as tax resistance) and others sought a Parliamentary investigation. Only Richard Carlile (a radical journalist championed by Shelley and who later did much to keep Shelley’s reputation alive) proposed a meaningful response: he and a few others proposed a general strike – which never materialized. Shelley as we shall see went much further. Scrivener notes: "...the key to understanding the uniqueness of Shelley’s poem is his proposal for massive non-violent resistance.”

His proposal for non-violent resistance famously appeared in one of the single greatest political poems written in the English language, The Mask of Anarchy.

Skelton became aware of this and so he wove Shelley into the fabric, so to speak, of his fashion show as well. "I wanted to bring light to the blood that was spilled at Peterloo," said Skelton. He was frustrated that the massacre is so poorly remembered today despite its immense significance and resonance in our modern times.

Skelton was also aware that,

“after Peterloo, mass meetings were banned, so people showed their allegiances in discreet ways. The way they would show unity was with one singular thing that was incredibly powerful en masse. One of the most discreet was a ribbon between the first and second buttonhole of their fustian jacket.”

Fustian is a type of cotton cloth that was worn by workers during the 19th century. It was heavy and durable, and according to historian Paul Pickering radical elements of the English working class chose to wear fustian jackets as a symbol of their class allegiance. This was especially marked during the Chartist era. Pickering has called the wearing of fustian "a statement of class without words.” Readers of this blog will remember that Shelley was also a major influence on the Chartists.

This clearly resonated with Skelton who picked up this theme and presented a clothing line with strong historical echoes and overt political overtones. In her review of the show Gonsalves noted that

"Each model was dressed in roughly hewn garments that were snagged, sewn and patched as though they had been worn, and loved, forever. Checks and stripes were mixed and matched, and a limited colour palette focused on earthy brown, rust, cream and mushroom.[There was a] “sense of authentic imperfection to the waistcoats, collarless shirts, thick twills and too-short trousers. This was reinforced by Skelton’s use of street-cast older men who looked like they had lived lives in these clothes rather than simply donned them backstage.”

So where does Shelley come in? Well, it appears that the principle lens through which Skelton came to view the massacre was Shelley’s Mask of Anarchy. So powerfully did Shelley’s poem impress him that he had his models recite the entire 91 stanzas! If you follow this link you will arrive at Skelton’s Instagram account and can watch a rehearsal with one of the models reading from the Mask of Anarchy. It looks fantastic, thought regrettably the audio quality is poor.

All of this reminds us of the extraordinary longevity of Shelley's influence. The Mask of Anarchy was not even published in his lifetime, yet it continues to inspire and influence creators and politically active thinkers to this day. Well done Percy.

- Aeschylus

- Amelia Curran

- Anna Mercer

- Arethusa

- Arielle Cottingham

- Atheism

- Byron

- Charles I

- Chartism

- Cian Duffy

- Claire Clairmont

- Coleridge

- Defense of Poetry

- Diderot

- Douglas Booth

- Earl Wasserman

- Edward Aveling

- Edward Silsbee

- Edward Trelawny

- Edward Williams

- England in 1819

- Engles

- Francis Thompson

- Frank Allaun

- Frankenstein

- Friedrich Engels

- George Bernard Shaw

- Gerald Hogle

- Harold Bloom

- Henry Salt

- Honora Becker

- Hotel de Villes de Londres

- Humanism

- James Bieri

- Jeremy Corbyn

- Karl Marx

- Kathleen Raine

- Keats-Shelley Association

- Kenneth Graham

- Kenneth Neill Cameron

- La Spezia

- Larry Henderson

- Leslie Preger

- Lucretius

- Lynn Shepherd

- Mark Summers

- Martin Priestman

- Marx

- Marxism

- Mary Shelley

- Mary Sherwood

- Mask of Anarchy

- Michael Demson

- Michael Gamer

- Michael O'Neill

- Michael Scrivener

- Milton Wilson

- Mont Blanc

- Neccessity of Atheism

- Nora Crook

- Ode to the West Wind

- Ozymandias

- Paul Foot

- Paul Stephens

- Pauline Newman

- Percy Shelley

- Peter Bell the Third

- Peterloo

- Philanthropist

- philanthropos tropos

- PMS Dawson

- Political Philosophy

- Prince Athanese

- Prometheus Unbound

- Queen Mab

- Richard Holmes

- romantic poetry

- Ross Wilson

- Sandy Grant

- Sara Coleridge

- Sarah Trimmer

- Scientific Socialism

- Shelleyana

- Skepticism

- Socialism

- Song to the Men of England

- Stopford Brooke

- Tess Martin

- The Cenci

- The Mask of Anarchy

- The Red Shelley

- Timothy Webb

- Tom Mole

- Triumph of Life

- Victorian Morality

- Villa Diodati

- William Godwin

- William Michael Rossetti

- Wordsworth

- Yvonne Kapp