Atheist, Lover of Humanity, Democrat

PERCY BYSSHE SHELLEY

Eleanor Marx Battles the Shelley Society!

In April of 1888, Eleanor Marx and Edward Aveling delivered a Marxist evaluation of the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley to an institution known as “The Shelley Society”. Composed of some of the giants of the Victorian literary community, the Society undertook research, hosted speeches, spawned local affiliates, republished important articles and poems (some for the first time!) and even produced Shelley’s The Cenci for the stage. But the Shelley Society was also a vehicle seemingly designed to obliterate Shelley’s left-wing politics. This article examines why the Shelley Society came into being and how it influenced the reception of Shelley for generations to come. Go behind the scenes with me as Eleanor Marx battles the forces of the male, bourgeois, Victorian literary establishment.

Eleanor Marx Battles the Shelley Society!

Eleanor Marx

In 1886, at the height of the Victorian era, a group of admirers of Percy Bysshe Shelley came together to form the Shelley Society. Among the founders were some of the intellectual giants of the age. For example, the list of distinguished names includes Edward Dowden, Buxton Forman, William Michael Rossetti, Arthur Napier (the Merton Professor of English Language and Literature at Oxford), Dr. Richard Garnett, George Bernard Shaw, Henry Salt, William Bell Scott (whose gorgeous painting of Shelley’s grave hangs in the Ashmolean Museum), Algernon Charles Swinburne, Francis Thompson, the Rev. Stopford Brooke, Edward Aveling and Eleanor Marx - to name only a few. At inception there were just over 100 but this number soon swelled to over 400 members. In addition, members of the general public were allowed to attend the meetings. As a result, while the inaugural lecture had an audience of over 500 - only a small proportion of whom were actual paid members. As it grew, the Society came to have chapters around the world. One thing that to me stands out from the list of eminent names, is what amounts to an ideological left/right fault-line which is at the heart of our story. And it actually speaks to Shelley’s protean character that he would find passionate adherents on both ends of the political spectrum.

A useful history of the literary societies of the 1880s (Shelley’s was not the only one) can be found in Angela Dunstan’s article, ‘The Newest Culte’: Victorian Poetry and the Literary Societies of the 1880s (In Nineteenth-Century Literature in Transition: The 1880s, edited by Penny Fielding and Andrew Taylor and published in 2019 by Cambridge). Dunstan points out that

“Though many in the Society were eminent literary scholars or critics the Notebooks make a concerted effort to legitimate opinions and close readings of rank and file members, demonstrating the capacity of vernacular poetry to be seriously studied by professional scholars and amateur enthusiasts alike.”

Also apparent to anyone reading through the Society proceedings is the presence of female voices. Dunstan writes,

Women were active in the Shelley society; notices of their involvement were regularly printed in “Ladies’ Columns:” in the press and reprinted in the Notebooks, and female members certainly attended the Society’s activities that contributed to debates. The Notebooks evidence debates over close readings of Alastor, for example, where ordinary female speakers confidently take on George Bernard Shaw or William Michael Rossetti over interpretation, and it is this democratic nature of literary societies’ debates which many outside of the societies and particularly in the universities found threatening.

“A stuffy Victorian, bourgeois morality suffuses the written record of the Society’s meetings.”

The Society published notes of its meeting, undertook research, hosted speeches, spawned local affiliates, republished important articles and poems (some for the first time!) and even produced Shelley’s The Cenci for the stage — all before it fell apart four years later. The goal was to make the scholarly study of Shelley more accessible to the general public - to in effect popularize Shelley and “democratise” literary criticism - and the meetings gained a reputation for an interest in critical rather than mere biographical exercises. Though largely forgotten by history, the proceedings of the Shelley Society constituted a momentous episode in the history of Shelley’s reception by the reading public; though one that is not without controversy.

Some, notably the socialist Paul Foot, were of the view that the Society had a deleterious effect on his reputation as a political radical. That said, Professor Alan Weinberg has noted that

We are reminded that prominent members of the Shelley Society present at the inaugural lecture were not averse to the poet's politics. If anything they tended to advance them. Succeeding lectures were devoted to Queen Mab (Forman), Prometheus Unbound(Rossetti), The Triumph of Life (Todhunter), The Mask of Anarchy (Forman), The Hermit of Marlow and Reform (Forman), Shelley and Disraeli's politics (Garnett) -all of which point positively or constructively to Shelley's radical sentiments.

The Rev. Stopford Brooke, 1885

The first speech at the inaugural meeting of the Society was delivered by the Reverend Stopford Augustus Brooke. Brooke was a prominent member of the Church of England who had risen to the post of “chaplain in ordinary” to Queen Victoria in 1875. He was a patron of the arts and was the leading figure in raising the money to acquire Dove Cottage (now administered by the Wordsworth Trust). In 1880, Brooke took the unusual step of seceding from the church because he no longer subscribed to its principal dogmas. In that same year Brooke also published a collection of Shelley’s poetry, Poems from Shelley, selected and arranged by Stopford A. Brooke (London: Macmillan & Co., 1880). In the speech, Brooke principally responds to the attacks on Shelley’s character that had been famously leveled by Mathew Arnold - opinions which have poisoned Shelley’s reception to the present day. The Society, said Brooke, desired to

“connect together all that would throw light on the poet’s personality and his work, to ascertain the truth about him, to issue reprints and above all to do something to further the objects of Shelley’s life and works, and to better understand and love a genius which was ignored and abused in his own time, but which had risen from the grave into which the critics had trampled it to live in the hearts of men.”

Matthew Arnold

Brooke also devoted considerable attention to rebutting the opinions of perhaps Shelley’s most effective critic, Matthew Arnold. Arnold’s judgement on Shelley was, Brooke thought, “victimized by his personal antipathy to Shelley’s idealism”, and Brooke found his views “petulant” and “prejudiced”. While others had attacked Shelley, none of them had the gravitas and influence of Mathew Arnold; Arnold who had characterized Shelley as a “beautiful and ineffectual angel, beating in the void his luminous wings in vain”. Arnold’s critique of Shelley appeared in a pair of essays written on Byron and Shelley and which were published together in his Essays in Criticism, Second Series (1888). You can find a beautifully written, approachable essay on the subject written by Professor Alan Weinberg here. Arnold’s encapsulation of Shelley’s character went on to have enormous influence. Weinberg:

On close examination (as will be shown), his [Arnold’s] argument is grossly superficial and unreliable. What has tended to carry weight is the authority of Arnold's position as eminent critic of his age (while this had currency) and the persuasiveness of his dictum which has connected with an ongoing antipathy or ambivalence towards Shelley. In the course of time, the dictum has become disentangled from the original argument and has acquired a life of its own.

Despite Professor Weinberg’s opinion expressed above, it is my view that Shelley’s radical politics were at best tolerated by Society members. It seems to me that from inception, there was a not so hidden agenda which came to dominate the Society’s proceedings. In seeking the “truth about Shelley”, Brooke for example proposed a distinctly religious and spiritual approach saying that Shelley’s “method was the method of Jesus Christ, reliance on spiritual force only…” Brooke saw Shelley’s life as “full of natural piety” and “noble ideals” while at the same times characterising his “aspirations” as “often unreal and visionary.” He saw Shelley as a man “not content with the world the way as it is” (fair enough) but as a “prophetic singer of the advancing kingdom of faith and hope and love.” (more problematic). A stuffy Victorian bourgeois morality suffuses the written record of the Society’s meetings. That morality even appears to have influenced membership applications. Henry Salt records that when Edward Aveling (a socialist living out of wedlock with the daughter of Karl Marx) attempted to join the Society, his application was turned down by a majority of members - “his marriage relations being similar to Shelley’s”. It was only through the “determined efforts” of William Michael Rossetti that the decision was over-turned (Yvonne Kapp, Eleanor Marx, p 450).

Frederick James Furnivall. William Rothenstein (attributed), Trinity Hall

Frederick James Furnivall, a prominent “Christian Socialist” who founded the London Working Men’s College and was a tireless promoter of English literature, lauded Brooke’s impassioned remarks by declaring that the Shelley Society would devote itself to responding to what he characterized as “Philistine” attacks on Shelley’s character and poetry. The chief “Philistine” referenced here was Cordy Jeaffreson who had recently authored a highly critical biography of Shelley: (The Real Shelley: New Views of the Poet's Life, 2 vols. 1885). What we see playing out here was a curious contest between rival camps to stake out exactly who the “real” Shelley was and just importantly, what he believed.

The Society’s goal, then, was not only to rebut attacks of Shelley, but also to find the “real Percy Bysshe Shelley”. Now, this is a mission which frankly resonates with me! However, at the hands of the Society, a very unusual, apolitical, quasi-religious Shelley would emerge as “real” Shelley. For his part, this would probably have come as an enormous surprise to Shelley himself - the self-declared atheist, humanist and republican who once wrote, "I tell of great matters, and I shall go on to free men's minds from the crippling bonds of superstition.” This battle for the soul of the “real” Percy Bysshe Shelley has never really gone away and it had real world consequences for me - something I wrote about in My Father’s Shelley - a Tale of Two Shelleys.

“I tell of great matters, and I shall go on to free men’s minds from the crippling bonds of superstition.”

However, the Society didn’t just want a new, more religiously-minded Shelley, whose “rotten ethics” (see below) had been explained away as youthful folly. Notwithstanding the fact that Society members had a somewhat permissive or indulgent attitude toward Shelley’s radicalism (Weinberg, above), there was nonetheless a distinct tendency to in effect depoliticise Shelley. For example, in a lecture to the Society on 14 April 1886, Buxton Forman complained that,

“Shelley is far more widely known as the author of Queen Mab than as the author of Prometheus Unbound. As the latter really strengthens the spirit while the former does not, we, who reverence Shelley for his spiritual enthusiasm, desire to see all that changed. And the change is advancing.“

The battle lines were clearly drawn. This fight was going to be about more than poetry; it was going to be about politics and it was going to be about class. A major stumbling block for the bourgeois members of the Society was clearly Shelley’s professed atheism. But there were ways to deal with this. Francis Thompson, for example, devoted a significant portion of his famous 1889 essay, Shelley, opining that Shelley could not really have been an atheist - because he was “struggling - blindly, weakly, stumblingly, but still struggling - toward higher things.” He had just died before he got there. While we might question the robustness of this evidence, his final argument was air-tight: “We do not believe that a truly corrupted spirit can write consistently ethereal poetry…The devil can do many things. But the devil cannot write poetry.”

Sara Coleridge daughter of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and an arch, bourgeois Victorian, reflected a widespread view when she wrote to a friend,

Sara Coleridge

"You are more displeased with Shelley's wrong religion than with Keats' no religion. Surely Shelley was as superior to Keats as a moral being, as he was above him in birth and breeding. Compare the letters of the two . . . see how much more spiritual is Shelley's expression, how much more of goodness, of Christian kindness, does his intercourse with his friends evince.”

One might well think that with friends like this, who needs enemies? I am not sure what is worse: the cringe-worthy dismissal of Keats, or the complete misappropriation of Shelley. And indeed, on another occasion one of the attendees said almost exactly that. Having listened to a speech about Shelley by Edward Silsbee that struck her as more of a “homily” than literary criticism, a Mrs. Simpson remarked that had Shelley heard the speech, he might well have said, “Save me from my friends.” Silsbee was reminded by another listener that between Dante and Shelley there was in fact another poet by the name of Shakespeare. Hagiography was very much the order of the day it would appear.

By the time the bourgeois members of the Shelley Society had finished with Shelley, poems like Queen Mab had been successfully relegated to the back pages of collected editions under the heading “Juvenilia“ - a designation suggested by Forman himself. Thus a cordon sanitaire had been established - Shelley’s radicalism was “ring-fenced”. He had in effect been reclaimed by proper society.

“The battle lines were clearly drawn. This fight was going to be about more than poetry; it was going to be about politics and it was going to be about class. ”

Why was this happening? Well, Shelley an important poet. But he had two very distinct and mutually antagonistic audiences - both loved him and for very different reasons. On the one hand was the working class and its socialist champions. On the other? The upper class who valued above all Shelley’s “spiritualism”, his love poetry and his lyricism. The two could have probably co-existed but for the annoying fact that Shelley himself was ill-fitted to the bourgeois camp. That and the fact Shelley was actually a revolutionary who had set himself implacably against them - most of his output was intensely political and revolutionary.

Karl Marx and his daughters with Engels.

Bourgeois Victorian literary society in the main objected Shelley’s radical heritage. They wanted to shift focus from this unwelcome aspect of his poetry and in this regard, his prose was for the most part ignored. Though perhaps presciently, it was Arnold who observed that Shelley’s letters and essays might better resist the “wear and tear of time” and “finally come to stand higher that his poetry”. Instead the focus was to shift to Shelley’s “mysticism”, his “spiritual enthusiasm” and above all his “lyricism”. Shelley’s political poetry was considered to be almost an aberration and a defect of character and grist for the “street socialists.”

For a glimpse into what they were reacting against, here is the view from the left (seemingly directly in response to the activities of the Shelley Society), courtesy of Friedrich Engels:

"Shelley, the genius, the prophet, finds most of [his] readers in the proletariat; the bourgeoisie own the castrated editions, the family editions cut down in accordance with the hypocritical morality of today.”

According to Eleanor Marx, her father,

“who understood the poets as well as he understood the philosophers and economists, was wont to say: “The real difference between Byron and Shelley is this: those who understand them and love them rejoice that Byron died at thirty-six, because if he had lived he would have become a reactionary bourgeois; they grieve that Shelley died at twenty-nine, because he was essentially a revolutionist, and he would always have been one of the advanced guard of socialism.”

Our story begins in earnest during the spring of 1887 when in a speech to the Society on 13 April one of the members, Alexander G. Ross delivered a bitter, class-based attack not upon Shelley himself, but upon Shelley’s socialist proponents. According to Paul Foot, Ross had been “enraged to discover that workers and even socialists were quoting a well-known English poet to their advantage”. Worse, of course, was the fact that Ross believed that Shelley’s “ethics were rotten.” As did many of his bourgeois colleagues.

“...they grieve that Shelley died at twenty-nine, because he was essentially a revolutionist, and he would always have been one of the advanced guard of socialism.””

Ross approached the issue by arguing that while,

“…no one can contest the right of anyone even though he may be a mere sans culotte who runs about with red rag, to quote Shelley when or where he pleases; but when the blatant and cruel socialism of the street endeavours to use the lofty and sublime socialism of the study for its own base purpose it is time that with no uncertain sound all real lovers of the latter should disembowel any sympathy with the former….It will be clearly understood that I strongly protest against any Imaginative writer being cited as an authority in favour of any political or social action…”

Edward Aveling

The distinction between “parlour socialism” and socialism actually put into action (“street socialism”) is quite something. Poetry was to be for poetry’s sake - and to hell with the politics. Now, in fairness, it is to be pointed out that both Rossetti and Furnivall both objected to elements of Ross’s address. Rossetti noted that a “great poet should put morals into his writings”, while carefully reinterpreting the Revolt of Islam’s message as “do good to your enemies; an annunciation of a universal reign of love.” The Revolt of Islam he concluded was “certainly not a didactic poem”. Furnivall complained that Ross seemed to treat poetry as a “toy”, and averred that “poets were men who felt certain truths more deeply than other men, and it was their work to put forth those thoughts.” Three of the avowed socialists in the room, Henry Salt, Aveling and George Bernard Shaw objected more specifically to the attacks on socialism.

Aveling, for his part, maintained that “the socialism of the study and the street was one and the same thing – and that constituted the beauty of modern socialism.” Shaw was highly critical as well, arguing that “a poem ought to be didactic, and ought to be in the nature of a political treatise - for poetry was the most artistic way of teaching those things a poet ought to teach.” One of the oddities of the debate turns on the argument about whether Shelley’s poetry was “didactic” or not. It will help modern readers if we unpack the coded language here. Opponents of Shelley’s didacticism were really reacting to his politics; or to be more accurate, the fact that socialists were championing him and as Paul Foot suggested, doing so to their advantage - in other words advancing the cause of socialism.

Annie Besant

Ross’s contentious address prompted Aveling and Marx to request an opportunity to present the case for an alternative version of the “Real Shelley”; a case for the “Socialist Shelley”. To them, what was happening in the 1880s was, plainly, a battle for the legacy of Percy Bysshe Shelley. Viewed from the left, the stakes would have been remarkably high. Marx and Aveling saw Shelley as someone who saw more clearly than anyone else “that the epic of the nineteenth century was to be the contest between the possessing and the producing classes.” This insight removed him “from the category of Utopian socialists and [made] him as far as was possible in his time, a socialist of modern days.” To see Shelley “castrated” (in the words of Friedrich Engels) and co-opted by the bourgeoisie was a call to arms. Aveling delivered the paper in April of 1888 though was careful to point out that “although I am the reader, it must be understood that I am reading the work of my wife as well as, no, more than, myself.”

Eleanor Marx was an extraordinary person who deserves far more attention from our modern society. According to Harrison Fluss and Sam Miller writing in Jacobin, Marx was

born on January 16, 1855, Eleanor Marx was Karl and Jenny Marx’s youngest daughter. She would become the forerunner of socialist feminism and one of the most prominent political leaders and union organizers in Britain. Eleanor pursued her activism fearlessly, captivated crowds with her speeches, stayed loyal to comrades and family, and grew into a brilliant political theorist. Not only that, she was a fierce advocate for children, a famous translator of European literature, a lifelong student of Shakespeare and a passionate actress.

To which we can add that she was also devotee of and influenced by Percy Shelley. Both Eleanor and Aveling were immersed in culture - much like Karl Marx himself. This was not Aveling’s first foray into the subject matter. In 1879 he had given a speech about Shelley to the Secular Society - described by Annie Besant as a “simple, loving, and personal account of the life and poetry of the hero of the free thinkers..” (Kapp, p. 451) This assessment, by the way, is yet another indication of the high regard accorded to Shelley by the socialist community. According to her Wikipedia entry, Besant was was a

“British socialist, theosophist, women's rights activist, writer, orator, educationist, and philanthropist. Regarded as a champion of human freedom, she was an ardent supporter of both Irish and Indian self-rule. She was a prolific author with over three hundred books and pamphlets to her credit.”

That she considered Shelley to be the “hero of freethinkers” is telling and a further reminder of the influence Shelley had on 19th century socialists. Kapp perceptively points out that:

“There can be no doubt that this lecture, though delivered by Aveling, was it to collaboration between two people who had long and devotedly studied the poet with equal enthusiasm, Aveling primarily as an atheist, Eleanor as a revolutionary…”

Eleanor Marx at 18

Marx and Aveling were at pains to point out that “the question to be considered…is not whether socialism is right or wrong, but whether Shelley was or was not a socialist.” Thus they first described a set of six distinguishing hallmarks of socialism and pointed out, “…If he enunciated views such as these, or even approximating to these, it is clear that we must admit that Shelley was a teacher as well as a poet.” The authors then set out their course of study:

(1) A note or two on Shelley himself and his own personality, as bearing on his relations to Socialism;

(2) On those, who, in this connection had most influence upon his thinking;

(3) His attacks on tyranny, and his singing for liberty, in the abstract;

(4) His attacks on tyranny in the concrete;

(5) His clear perception of the class struggle; and

(6) His insight into the real meaning of such words as “freedom,'’ “justice,” “crime,” “labour,” and “property”.

Of Shelley’s personality, Marx and Aveling seem principally interested in adducing (with copious citations from The Cenci, Prince Athanese, Queen Mab, Laon and Cythna and Triumph of Life) Shelley’s connection to the politics of his era, noting his advanced thinking on issues such as Napoleon and evolution:

“Of the two great principles affecting the development of the individual end of the race, those of heredity and adaptation, he had clear perception, although day as yet we are neither accurately defined nor even named. He understood that men and peoples were the result of their ancestry and their environment.”

As for Shelley’s influences, the authors begin by contrasting Shelley with Byron.

In Byron they suggest,

“…we have the vague, generous and genuine aspirations in the abstract, which found their final expression in the bourgeois-democratic movement of 1848. In Shelley, there was more than the vague striving after freedom in the abstract, and therefore his ideas are finding expression in the social-democratic movement of our own day….He saw more clearly than Byron, who seems scarcely to have seen it at all, that the epic of the nineteenth century was to be the contest between the possessing and the producing classes. And it is just this that removes him from the category of Utopian socialists, and makes him so far as it was possible in his time, a socialist of modern days.

They then enumerate those whom they consider his prime influences: François-Noël Baboeuf, Rousseau, the French philosophes, the Encyclopaedists, Baron d’Holbach, and Denis Diderot. The addition of Diderot to this list is interesting. We now know that as early as 1812, Shelley had ordered copies of Diderot’s works - but this was not widely known in the 19th Century. I certainly feel that the spirit of Diderot suffuses Shelley’s philosophy and writings. Interestingly, Aveling and Marx thought very highly of Diderot as well, averring that Diderot “was the intellectual ghost of everybody of his time” - an assessment described to me as a “penetrating insight” by Andrew Curran the author of the excellent Diderot and the Art of Thinking Freely.

“We simply can not underestimate the influence Shelley had on the socialists of this period.”

Godwin was also singled out, hardly surprisingly - though as Marx and Aveling ruefully note, “Dowden’s Life has made us all so thoroughly acquainted with the ill-side of Godwin that just now there may be a not unnatural tendency to forget the best of him.” But of real interest is the time spent adducing the under-appreciated influence of “the two Marys” (Wollstonecraft and Godwin), and the perspective is instructive. “In a word,” Marx and Aveling suggest,

the world in general has treated the relative influences of Godwin on the one hand and of the two women on the other, pretty much has might have been expected with men for historians. Probably the fact that he saw so much through the eyes of these two women quickened Shelley's perception of woman's real position in society and the real cause of that position….this understanding…is in a large measure due to the two Marys.

Shelley’s espousal of what we would now call feminist causes was extremely unusual for his time. Clearly it resonated with Marx and Aveling who comment that “it was one of Shelley's "delusions that are not delusions" that man and women should be equal and united. And Paul Foot seizes on and develops this theme in his speech to the 1981 Marxism Conference in London.

“It’s not just that he saw that women were oppressed in the society, that the women were oppressed in the home; it’s not just that he saw the monstrosity of that. It’s not even just that he saw that there was no prospect whatever of any kind for revolutionary upsurge if men left women behind. Like, for example, in the 1848 rebellions in Paris where he men deliberately locked the women up and told them they couldn’t come out to the demonstrations that took place there because in some way or other that would demean the nature of the revolution. It wasn’t just that he saw the absurdity of situations like that. It was that he saw what happened when women did activate themselves, and did start to take control of their lives, and did start to hit back against repression. Shelley saw that what happened then was that again and again, women seized the leadership of the forces that were in revolution! All through Shelley’s poetry, all his great revolutionary poems, the main agitators, the people that do most of the revolutionary work and who he gives most of the revolutionary speeches, are women. Queen Mab herself, Asia in Prometheus Unbound, Iona in Swellfoot the Tyrant, and most important of all, Cythna in The Revolt of Islam. All these women, throughout his poetry, were the leaders of the revolution and the main agitators.”

I have written myself at length on the fact that much of Shelley’s radicalism concentrates on what he would have considered twinned targets: the monarchy and religion (religion being for Shelley the “hand-maiden of tyranny”). So it is not surprising that when Marx and Aveling came to the third part of their presentation, they pointed out that at the root of Shelley’s antagonism to the tyranny of church and state was the belief that the ultimate problem was

“the superstitious in the capitalistic system in the empire of class…. And always, every word that he has written against religious superstition and the despotism of individual rulers may be read as against economic superstition and the despotism of class.”

They also pointed out the extent to which Shelley’s concern with tyranny was more than just abstract, he is lauded not just for his attention to Mexico, Spain, Ireland and England, but also for his attacks on individuals: Castlereagh, Sidmouth, Eldon and Napoleon. “He is forever,” they wrote, “denouncing priest and king and statesman.”

Of most interest to me is the fourth section in which Marx and Aveling turn to Shelley’s understanding of “class struggle.” What makes Shelley a socialist more than anything else,

“is his singular understanding of the facts that today tyranny resolves itself into the tyranny of the possessing class over the producing, and that to this tyranny in the ultimate analysis is traceable almost all evil and misery. He saw that the soul-called middle class is the real tyrant, the real danger at the present day.”

Shelley by George Clint after Amelia Curran

To support this position, a veritable arsenal of quotations is deployed. From what they call the Philosophic View of Reform, from Godwin, from letters to Hookham and Hitchens, and from Swellfoot the Tyrant, Peter Bell the Third and Charles the I. The effect is spectacular. For example, this from Swellfoot: “Those who consume these fruits through thee [the goddess of famine] grow fat. / Those who produce these fruits through the grow lean". The cumulative effect is to place Shelley in a tradition that leads directly to Marx, Engels and modern socialism. And, indeed, the resonance and reverberation of the language is uncanny.

Marx and Aveling conclude the section by quoting Mary to great effect (from her notes to her collected edition): “He believed the clash between the two classes of society was inevitable, and he eagerly ranged himself on the peoples side.” They clearly see Shelley as a direct precursor to Marx and Engels and it is hard to disagree with them. In an unusual turn of phrase considering their undoubted atheism, they had earlier referred to Shelley as a philosopher and a prophet - a term you will have seen Engels use as well in the quotation cited above. Elsewhere, Marx and Aveling refer to him as the “poet-leader”. In a truly remarkable passage they seem to treat Shelley’s writing, his value system, almost as a “sacred text”:

This extraordinary power of seeing things clearly and of seeing them in their right relations one to another, shown not alone in the artistic side of his nature, but in the scientific, the historical, the social, is a comfort and strength to us that hold in the main the beliefs, made more sacred to us in that they were his, and must give every lover of Shelley pause when he finds himself departing from the master on any fundamental question of economics, a faith, of human life.”

It was not uncommon for atheists, including Shelley, to use the words of religion when attempting to convey passionately held beliefs. And passages and expressions such as these mean that we simply can not underestimate the influence Shelley had on the socialists of this period.

“[What makes Shelley a socialist] is his singular understanding of the facts that today tyranny resolves itself into the tyranny of the possessing class over the producing class.”

In their final section, Marx and Aveling consider Shelley’s use of language, focusing on the words, “anarchy, freedom, custom, crime and property” as well as the concept of the “governing class”. Perceptively and shrewdly, they note that for Shelley the accepted meaning of certain phrases does not align with reality. Thus they touch on what came to be understood as Shelley’s famous capacity for ironic inversion. For example his deployment of the term “anarchy” to describe the then current social system and “rule of law”. For Shelley, they say, anarchy, was “God and King and Law…and let us add…Capitalism.”

On the question of “property”, Marx and Aveling reach their denouement. They begin by quoting a passage from A Philosophical View of Reform that directly anticipates Marx:

Labor, industry, economy, skill, genius, or any similar powers honourably or innocently exerted, are the foundations of one description of property. All true political institutions ought to defend every man in the exercise of his discretion with respect to property so acquired… But there is another species of property which has its foundation in usurpation, or imposture, or violence, without which, by the nature of things, immense aggregations of property could never have been accumulated.

They then paraphrase this in the language of what they call scientific socialism:

“A man has a right to anything his own labour has produced, and that he does not intend to employ for the purpose of injuring his fellows. But no man can himself acquire a considerable aggregation of property except at the expense of his fellows. He must either cheat a certain number out of the value of it, or take it by force.”

With citations from Song to the Men of England, Fragment: To the People of England, Queen Mab and a letter to Hitchener, Marx and Aveling make the case that Shelley understood,

the real economic value of private property in the means of production and distribution, whether it was in machinery, land, funds, what not. He saw that this value lay in the command, absolute, merciless, unjust, over human labour. The socialist believes that these means of production and distribution should be the property of the community. For the man or company that owns them has practically irresponsible control over the class that does not possess them.

And this, they conclude, are the “teachings of Shelley.” And as they are also the teachings of socialism, the two are one and the same thing. Thus Marx and Aveling end with the ringing words, “We claim him as a socialist.”

““We claim him as a socialist.””

According to Marx’s biographer Yvonne Kapp, Shelley’s Socialism was first published by To-day: The Journal of Scientific Socialism in 1888 (Yvonne Kapp, Eleanor Marx, p. 450). It also appeared as a pamphlet in an edition of only twenty-five copies published (presumably by the Shelley Society) for private circulation under the title Shelley and Socialism. In 1947, Leslie Preger (a young Manchester socialist who had fought in the Spanish Civil War) arranged to have it published, with an introduction by the Labour politician Frank Allaun through CWS Printing Work. The Preger edition can be found online through used book services such as AbeBooks. The version published by Preger and that which appeared in To-Day are somewhat different. The version which appears in To-Day appears to have been lightly edited and omits several selections from Shelley’s poetry that appear in the Preger edition. My assumption is that Preger reproduced the pamphlet version released by the Shelley Society. The version I have made available (see link below) is based on Preger and thus is the only complete and “authoritative” version of the speech (as delivered) available on line. You may read it online in it entirety for the first time.

In their speech, Marx and Aveling refer to a second part which they intended to deliver upon some future occasion. Either the second installment has been either lost or perhaps it was never delivered. However, Kapp tantalizingly points out that Engels in fact translated the second part into German for publication in Germany by Die Neue Zeit (Kapp p. 450). No trace of it appears to exist - a loss for us all given the intended subject matter discussed in the speech.

Frank Allaun, author of the preface to the Preger edition, offered this encapsulation of the speech: “A Marxist evaluation of the poetry of Percy Bysshe Shelley.” He concludes his preface with this sage assessment:

“Shelley, who died when his sailing boat sinking a storm in 1822, lived when the Industrial Revolution was only beginning. The owning class had not yet "dug their own graves" by driving the handloom weavers and other domestic workers from their kitchens and plots of land into the "dark satanic mills" alongside thousands of other operatives. Conditions were not ripe for the modern trade union and socialist movement. Had they been so Shelley would have been their man.”

Of the authors, George Bernard Shaw said "he (Aveling) was quite a pleasant fellow who would've gone to the stake for socialism or atheism, but with absolutely no conscience in his private life. He said seduced every woman he met and borrowed from every man. Eleanor committed suicide. Eleanor's tragedy made him infamous in Germany". Shaw added, "While Shelley needs no preface that agreeable rascal Aveling does not deserve one.”

You can read a wonderful encapsulation of Eleanor Marx and her legacy in the Jacobion, here. And you can buy Kapp’s biography of Marx here, though I strongly suggest you instead order it through your local bookseller.

Click the button to go to the speech.

The footnotes in all of the sources are antiquated and refer to out of date editions of Shelley’s poetry and prose - I will in due course provide references to more modern, available texts. Interestingly, there is no mention of the speech in any of the major Shelley biographies. Not even Kenneth Neill Cameron, a Marxist, alludes to it. Nor does Paul Foot reference it in Red Shelley. Thus, it would appear that Aveling’s and Marx’s effort to “claim Shelley as a socialist” had little effect either of the Society or upon public opinion in general. Perhaps this was predictable given the tenor of the times. As Foot observed:

Paul Foot

“In the 1840s as Engels noted, Shelley had been almost exclusively the property of the working class the Chartists had read him for what he was, a tough agitator and revolutionary. The effect of the Shelley-worship of the 1880s and 1890s was too weaken that image; to present for mass consumption a new, wet, angelic Shelley and to promote this new Shelley with all the influence and wealth of respectable academics and publishers.”

Paul Foot offers a disquieting account of the struggle during these years in chapter 7 of Red Shelley. It was a struggle which was largely won by the right and lost by the left. And it would be decades before Kenneth Neil Cameron emerged in the early 1950s to begin the lengthy and arduous process of salvaging Shelley’s left wing credentials. For generations, the Shelley that was embraced by Chartists, by Marx and Engels, would be subsumed by a tidal wave of mawkish Shelleyan “sentimentality’. Gone would be his revolutionary political ardour and in its place appeared a carefully curated selection of poetry designed to showcase only Shelley’s lyrical capabilities - his love poems.

Interestingly, to call Shelley a “love poet” can be intensely misleading. Many modern readers encountering the term “love poet” will think immediately of romantic or sexual love - and there is no doubt that Shelley wrote many poem that were almost purely romantic. However, when Shelley speaks of love, you have to look carefully at what he is saying, and what he is almost always talking about is empathy, that is the ability to imagine and understand the thoughts, perspective, and emotions of another person; to put yourself in their shoes, as it were. Shelley should therefore be thought of as the “poet of empathy” and of revolutionary love.

“Shelley should be thought of as the poet of empathy and, if anything, of revolutionary love.”

Isabel Quigley’s selection of Shelley’s Poetry: “No poet better repays cutting.”

For example, in the first part of the 20th century, Gresham Press offered a highly popular selection of poems by English poets. In the introduction to the Shelley volume, the poet and editor Alice Meynell (also a vice president of the Women Writers' Suffrage League) cheerfully announced that “ This volume leaves out all Shelley’s contentious poems.”

As recently as 1973, Kathleen Raine, in Penguin’s Poet to Poet series, omitted important poems such as Laon and Cythna - as well as most of the rest of his overtly political output. And she did so with considerable gusto, stating explicitly that she did so “without regret”. In a widely available edition of his poetry, the editor, Isabel Quigly, cheerfully notes, “No poet better repays cutting; no great poet was ever less worth reading in his entirety".

Fortunately Shelleyan scholarship has now long since passed through this dark period in his reception. The annus mirabilis in this regard was 1980, the year in which PMS Dawson published his book, Unacknowledged Legislator: Shelley and Politics, Paul Foot published Red Shelley, and Michael Scrivener published Radical Shelley: The Philosophical Anarchism and Utopian Thought of Percy Bysshe Shelley. All three owe an enormous debt to perhaps the greatest of Shelley’s politically minded biographers, the Marxist Kenneth Neill Cameron whose magisterial volume The Young Shelley: Genesis of a Radical appeared in 1958. This is a book of which one can truly be in awe.

Let Fury Have the Hour - Shelley and The Clash

One of my favourite bands from the 1970s was Buzzcocks, an English outfit fronted by a man named Pete Shelley. Pete had been born as Peter McNeish; but when he took to the stage he changed his name to honour his favourite romantic poet. I was enthralled by this idea and when I wrote my masters thesis, I included three musical epigraphs: two from the Sex Pistols and one from Buzzcocks. It was perhaps a stretch - however in my youthful rebellious mind I thought it was apt.

But was it really so far-fetched to tie together punk music and romantic poetry? To test this, I thought I would be fun to have a quick glance at one of the classics of the era to see if there are, in fact, any Shelleyan overtones. That classic? Clampdown by The Clash from the album London Calling. Let’s dig in.

Let Fury Have the Hour - Shelley and The Clash

On 8 May 1970 the Beatles issued their final album and broke up - the music that I had grown up with was, I thought, finished and the world was unraveling. Ah youth. I was not yet 16. Then, when I was barely 18, the chess and hockey started - and things really went nuts.

In the summer of 1972 the American Bobby Fischer faced Boris Spassky, a Russian, in a chess (chess!!!!) match that came to be known as the “Match of the Century”. It dominated newspaper headlines for months. Without question this will be looked back on as the most famous chess match ever played - though not necessarily because of the chess - though it was brilliant. Garry Kasparov, a subsequent world champion, explains why:

“I think the reason you look at these matches was not so much due to the chess factor but rather the political element. This was inevitable because in the Soviet Union chess was treated by the Soviet authorities as a very important and a useful ideological tool to demonstrate the intellectual superiority of the Soviet communist regime over the West. That is why Spassky’s defeat was treated by people on both sides of the Atlantic as a crushing moment in the midst of the cold war”.

“Then the chess and hockey started - and things really went nuts.”

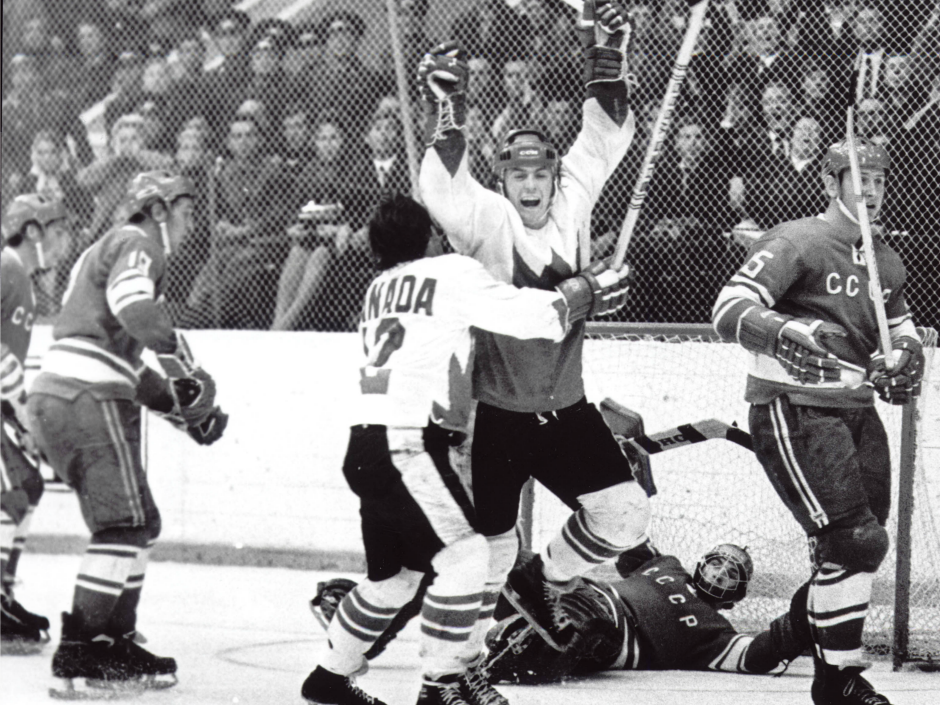

Spassky (left) and Fischer in 1972

Spassky had barely resigned the match on 31 August 1972 when a mere 2 days later a very different and far more physical cold war contest began. On 2 September 1972 Canada and the Soviet Union squared off in what came to be known as the Summit Series. For decades the Soviets had dominated international hockey largely because the Canadian had never “iced” their professional players. For the first time, our best would face their best. 26 grueling days later the series ended with a dramatic last minute goal - Canada had defeated the Soviet Union. I know exactly where I was.

In that same summer, the Black September terrorists kidnapped and murdered Israeli athletes at the Munich Olympics. Then came an oil embargo that roiled the world. Next came Nixon’s epic disgrace and resignation. Over the next few years we would learn about the deaths of millions of Cambodians at the hands of the Khmer Rouge and Pol Pot. During this same period wars erupted across Africa as former colonial states fought for independence in places like Rhodesia and South Africa.

In 1978 we were shocked by the mass suicides in what was called Jonestown. We were also introduced to the concept of serial killers thanks to the predations of David Berkowitz (the “Son of Sam”) and Ted Bundy. The threat of nuclear disasters also dominated our world culminating in Three Mile Island accident in 1979. The soundtrack for much of this period was a bizarre mishmash of “prog rock” and disco. Below the surface, however, we took shelter with Bruce Springsteen, Patti Smith and holdovers from the late 60s.

Paul Henderson scores the winning goal with seconds left.

I am not going to suggest that the 1970s were uniformly terrible. Every era has its good and its bad. The chess was terrific and Canada’s national hockey team accomplished what was thought to be impossible. Mother Theresa won the Nobel peace Prize. Arthur Ashe won Wimbledon. Hank Aaron broke Babe Ruth’s home run record. Louise Brown became the world’s first test tube baby. Secretariat blew away the field to win the Triple Crown. Billie Jean King beat that fool Bobby Riggs. Some amazing movies got made: Clockwork Orange, The French Connection, Chinatown, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Taxi Driver, and Alien. And musically, the decade went out in a blaze of rock and roll we called punk.

Somehow, during all of this confusion, I managed to come of age and become a man. I graduated from high school in 1973 and eventually went to University. I fell in love, out of love and back in love. I cemented friendships which have endured to this day. But what sustained me for the latter part of this decade was a couple of things: my love of Percy Bysshe Shelley’s and music - specifically, punk rock.

“ Let fury have the hour, anger can be power - The Clash”

I was young and fairly revolutionary in my thinking. I was studying English literature - Shelley and Blake were my heroes. I liked them because they opposed the status quo - they fought the system. Much like Shelley, I could not abide Wordsworth - not because of the poetry - but because he became a backsliding, reactionary, counter-revolutionary. He became as, Mary Shelley so succinctly put it, a “slave”. And there is nothing that youthful rebels despise more than seeing their heroes back-silde into conformity.

In the 1970s, Shelley was still an outcast in the academic community – his reputation had been almost irreparably damaged by the likes of Eliot and Leavis. It was only just then in the process of being resuscitated thanks to scholars such as Milton Wilson (with whom I had the luck to later complete my masters at the University of Toronto), the great Kenneth Neill Cameron and Eric Wasserman. To study Shelley was almost an act of rebellion in and of itself. He was a lot of very cool things: atheist, vegetarian, philosophical anarchist, feminist, anti-monarchist, republican and lots more. He was seriously rock and roll.

One of my favourite bands from the era was Buzzcocks, an English outfit fronted by a man named Pete Shelley. Pete had been born as Peter McNeish; but when he took to the stage he changed his name to honour his favourite romantic poet. I was enthralled by this idea and when I wrote my masters thesis, I included three musical epigraphs: two from the Sex Pistols and one from Buzzcocks. It was perhaps a stretch - however in my youthful rebellious mind I thought it was apt.

But was it really so far-fetched to tie together punk music and romantic poetry? To test this, I thought I would be fun to have a quick glance at one of the classics of the era to see if there are, in fact, any Shelleyan overtones. That classic? Clampdown by The Clash from the album London Calling. Let’s dig in.

To make this work, you really need to do me a favour. You need to follow this link or this one or this one and give the song a few listens. When you are done that, come on back and let’s continue.

Clampdown is a song about the loss of youthful ideals. Written by Joe Strummer, one of the band's most fiercely anti-establishment members, the song charts the manner in which this can happen. And just as Shelley understood importance of language, so too did Strummer. He laments the manner in which society teaches its "twisted speech to the young believers"; the manner in which youthful revolutionary instincts are dulled by an inculcated appetite for money and the acquisition of luxuries.

We will teach our twisted speech

To the young believers

We will train our blue-eyed men

To be young believers

“You grow up and you calm down - you’re working for the clampdown. - The Clash”

The tendency of revolutions to fail to bring about meaningful change and progress was always a concern for Shelley; it is one of the reasons I think he was almost obsessed with language. I am not sure that, apart from Shakespeare, there has ever been a writer who not only understood the power of language, but who mastered it so completely. Words can free us; words can enslave us. Professor Michael O’Neill in his keynote address to the Shelley Conference 2017 digs into how Shelley uses language to challenge custom and habit; or, as O’Neill puts it, to "invite [his readers] to reconsider the world in which we live." This, to me, strikes at the heart of Shelley’s entire output; this was a man who believed that poetry (or more generally cultural products) could literally change the world. I have written about this here and here.

In the case of Clampdown, Strummer castigates the youth of all generations, alleging, "You grow up and you calm down / You're working for the clampdown. For his part, he imagines a revolutionary resistance to the state:

The judge said five to ten-but I say double that again

I'm not working for the clampdown

No man born with a living soul

Can be working for the clampdown

How familiar does this start to sound? I hear echoes of Prometheus facing down the Jupiter in Act 1 of Shelley’s Prometheus Unbound. Both speakers see themselves as martyrs. In Clampdown, the protagonist is charged by the police for an act of rebellion against the state. At his trial, he defies his judge and asks for his sentence to be doubled. Then, spitting with anger:

Kick over the wall cause governments to fall

How can you refuse it?

Let fury have the hour, anger can be power

D’you know that you can use it?

“Kick over the wall cause governments to fall. - The Clash”

The state, however, is seen as cunning and subversive. It gets inside your head, it coerces you subtly; wears you down, urges conformity. Why fight the system? You will never win. At this point I hear the furies from Act 2 of Prometheus Unbound taunting Prometheus. Strummer himself imagines a subversive internal dialogue that erodes the will to resist:

The voices in your head are calling

Stop wasting your time, there's nothing coming

Only a fool would think someone could save you

Even the members of one's own class are not to be trusted:

The men at the factory are old and cunning

You don't owe nothing, so boy get runnin'

It's the best years of your life they want to steal

He then moves to the accusatory crescendo of the song:

You grow up and you calm down

You're working for the clampdown

You start wearing the blue and brown

You're working for the clampdown.

“Shelley was a revolutionist and he would always have been one of the advanced guard of socialism - Marx”

Joe Strummer

And once this happens the conversion is complete. Youthful rebellion is replaced by aging complacency and conformity - the young rebellious Wordsworth becomes the old reactionary Wordsworth. The revolution, in other words, fails. It seems to me that there are some surprising echoes here of both Prometheus Unbound and Shelley's own life. The voices inside Joe Strummer’s head are the Clash's version of Mercury and the Furies. We all hear them. Unlike Shelley, however, Strummer had no real sense of the perfectibility of man. He saw only chaos and degradation – the endless cycles of revolution-tyranny-revolution. Shelley saw a way out. Not so Joe Strummer.

Shelley, drawn by Edward Williams (If only PBS had a publicist!)

As a young man, despising Wordsworth as a sellout and extolling Shelley as a revolutionary, I clung to the message of Clampdown: which I took to be: "Don't grow up and turn into your old man; don't conform." Be Shelley, not Wordsworth. Now, of course, there was one flaw in my thinking. Shelley died before he had a chance to turn into a Wordsworth; before the voices in his head subverted his revolutionary impulses. And he has detractors who suggest that had he not died, this is exactly what would have happened - he would have grown up and become a proper Tory.

Possibly. But maybe not. Not everyone is destined to become a Wordsworth. Think for example of the great crusading journalist (and Shelleyan) Paul Foot. I wrote about him here. Or what about Ursula Leguin (another Shelleyan). Leguin and Foot never for a minute surrendered their ideals. I like to think Shelley would never have surrendered them either, would never have worked for the clampdown. And I am not alone, here is what Karl Marx said:

"The real difference between Byron and Shelley is this: those who understand and love them rejoice that Byron died at 36, because if he had lived he would have become a reactionary bourgeois; they grieve that Shelley died at 29, because he was essentially a revolutionist and he would always have been one of the advanced guard of socialism."

But those voice in our heads........they keep calling - don’t they. Shelley knew that. Contrary to what many think, Shelley was not a utopian and Prometheus Unbound is not his vision of utopia. Have a close look at Act 3. After the forces unleashed by Demogorgon oust Jupiter, Demogorgon does not vanish - Shelley envisages that he retires to a cave beneath the world from whence he may be called forth again in the event the revolution fails. This underscores Shelley’s lifelong skepticism: you can fight for change, you can win, but you can just as easily lose everything you have gained down the road. The only cure? Eternal vigilance and an ever-renewing revolutionary imagination.

The rebellious spirit of the romantic poets is really not so far removed from that of the punk rock musicians of the 1970s and 80s. This is why the study of poets like Shelley (in particular) can offer so much to us today. There is a commonality of spirit, a sort of intellectual esprit de coeur, that unites them - that unites are true revolutionaries. And they all tell us one thing: we grow old at our own peril.

“Let fury have the hour, anger can be power”.

Roland Duerksen: A Shelleyan Life

In the early summer of 2017, I received a letter from the daughter of the noted Shelley scholar Roland Duerksen. Susan had read my article “My Father’s Shelley” and it had struck a chord. She wanted to connect me with her father, now 91 years old and living in New Oxford, Ohio. Roland is the author of two noteworthy and important books on Shelley: "Shelleyan Ideas in Victorian Literature" and "Shelley's Poetry of Involvement". His analysis is penetrating and nuanced, the style conversational and accessible. But it is his overall approach which makes him different, it is imbued with a humanity that reflects well both on himself and his subject. This much I knew, but I knew less about the man himself. I was thrilled that Susan had reached out to me, it was a chance to meet one of the great Shelleyans, but I had no idea whatsoever of the magic which lay in wait for me.

In the early summer of 2017, I received a letter from the daughter of the noted Shelley scholar Roland Duerksen. Susan had read my article “My Father’s Shelley” and it had struck a chord. She wanted to connect me with her father, now 91 years old and living in Oxford, Ohio. Roland is the author of two noteworthy and important books on Shelley: Shelleyan Ideas in Victorian Literature and Shelley's Poetry of Involvement. His analysis is penetrating and nuanced, and his style is conversational and accessible. But it is his overall approach that makes him different: Roland's work is imbued with a humanity that reflects well on both himself and his subject. This much I knew, but I knew less about the man himself. I was thrilled that Susan had reached out to me. She offered me a chance to meet one of the great Shelleyans, but I had no idea whatsoever of the magic that lay in wait for me.

Below, I give you a little about the life and thought of Roland Duerksen, which I gathered from him in interviews that took place over a couple of days. In this essay, I want to share Roland's early life story, from his Mennonite rearing in Dust Bowl Kansas to his development into one of the truly great Shelley scholars. In a second essay, which will appear shortly on our website, I will dive into Duerksen's ideas about Shelley and his later life, including his important work as an activist. Stay tuned!

Roland possesses an extraordinary memory and can quote Shelley at length. Though he has been retired for years, his grasp of the nuances of Shelley’s poetry was nothing short of astonishing. He was also an amusing and friendly interlocutor. He has the ability to put one at ease; you feel like you are out on a country porch, chatting with an old friend you have known for years.

Roland Duerksen was born 23 October 1926, just 7 miles from Goessel, Kansas. Goessel is a small farming community that is located almost dead center on the US map. In Goessel you will find, among other things, the Mennonite Heritage and Agricultural Museum, a hint of the community’s religious and farming roots. To get there, one takes Interstate 135 north from Wichita to Newton, before making a quick right on Highway 15. In seven miles you will find yourself in Goessel. The 240-acre family farm can be found two side roads north and four to the east, another seven miles from town.

Alexanderwohl Mennonite Church, Molotschna, Ukraine.

Roland’s ancestors came to this place in 1874, part of a mass migration of Mennonites fleeing persecution in Russia. The history is fascinating. Originally Dutch, the community emigrated in the early 17th century to what was then South Prussia, and then later in the 1820s to Molotschna, Russia (in what is now Ukraine). The Mennonites had been on the move for centuries, persecuted for what were considered to be heretical beliefs. In Russia they were promised exemption from military service, the right to run their own schools, and the ability to self-govern their villages. In the late 19th century, however, Russia decided to revoke all special privileges that had been given to the community. The leaders of the community made a momentous decision: they would take their entire community to the United States of America. Church elders organized an exploratory mission in 1873 to ascertain the available options. After visiting Texas and Kansas, the leaders returned with the recommendation that the community emigrate to Kansas. At the time, the United States was desperate for skilled farming immigrants, and the Mennonites fit the bill. The community quickly set out, eventually settling in Buhler and Goessel, two towns in rural Kansas. In 1874, after a long, arduous trip, Roland's grandfather Johann (then aged 16) reached his new life in the Goessel community. (Read more about this extraordinary migration here.)

Roland Duerksen in 1934 or 35.

During their first 50 or so years in America, the Goessel farmers prospered essentially as they had expected. Life was persecution-free and work was productive. Free to worship as they pleased, the Duerksens attended Alexanderwohl Church (pictured to the right). Originally built in 1886, it was refurbished substantially over the years, but is still there to this day.

Then came the hard times. By the time Roland was 3, the stock market had crashed; before he was 8, the American West was in the grips of the great drought of the 1930s; and as he turned 16, America entered a World War. How does this compare with your youth?

We all know the drought of the 1930s as the “Dust Bowl” because it resulted in immense dust storms, known as “black blizzards,” which wreaked havoc on America's farms. They came in waves, hitting America hard in 1934, 1936, 1939, and 1940.

On 14 April 1935, a mammoth series of these storms struck the American West. They have since come to be known as “Black Sunday.” They were every bit as bad as their name suggests. Associated Press reporter Robert Geiger (famed for having given the Dust Bowl its name) was caught on a highway north of Boise City, Idaho as he raced at 60 miles an hour in a failed attempt to outrun it. He writes of what he saw as follows:

Dust storm approaching Stratford, Texas, 1935

“The Black Sunday event was one of the less frequent but more dramatic storms borne south on polar air originating in Canada. Rising some 8,000 feet into the air, these churning walls of dirt generated massive amounts of static electricity, complete with their own thunder and lightning ... Temperatures plunged 40 degrees along the storm front before the dust hit.”

“A farmer and his two sons during a storm in Cimaron County, Oklahoma April 1936." Arthur Rothstein.

Goessel is located on the edge of where these storms hit hardest, and the bad weather severely impacted the Duerksens. The family, which consisted of Roland, his parents, and three siblings, was very poor; Roland's father often struggled to make his payments on the farm. Unlike so many, however, the family weathered the Great Depression and emerged from the years of hardship in one piece.

The family were devoted Mennonites. Ironically, Roland's childhood faith may have partly inspired his attraction to England's most famous atheist poet (I will return to this idea). Mennonites believe that baptism should result from an informed decision of which only adults are capable; thus the religion tends to stress individual choice and the freedom of conscience in religious and ethical matters. For much of history, this spirit of non-conformity made them a target of persecution within European societies.

Mennonites place the teachings of Jesus, including pacifism, non-violence, and charity, at the heart of their religion. According to Bethel College, a Christian school Duerksen attended, Mennonites base their faith and lifestyle around the following traits: "service to others; concern for those less fortunate; involvement in issues of social justice; and emphasis on peaceful, nonviolent resolution of community, national and international conflicts.” It is this last feature of their belief system that has resulted in Mennonites’ opposition to war and their refusal to serve in the military. The corollary of this passivism is of critical importance, because Mennonites are dedicated to creating a “more just and peaceful society.” Of course, these same values can be found in Shelley's writing, even if Shelley and the Mennonites took very different paths towards them.

In other ways, however, Roland's upbringing hardly seemed calculated to produce a great literary scholar. His mother, who drew on evangelicalism as well as the Mennonite faith, “was opposed to the reading of novels because they do not contain the truth,” Roland says. This meant that as he grew, books were a rarity and the church was central to his existence. Roland attended a one-room school house which had only a few short shelves of books. When I asked him about this, Roland replied,

"I must say my whole introduction to books came much later. I did read some books. I remember Robinson Crusoe and [books like that]. But, it was very sparse and I was figuring, I guess, that I [was destined to] be a farmer. So why should I read a lot?"

The future, however, had something very different in store for Roland Duerksen: Shelley lay in wait…

Roland Duerksen, circa 1948.

Roland attended high school in Goessel, graduated in 1944, and immediately registered as a conscientious objector. The war was reaching a climax; millions of young Americans were enlisted and fighting overseas. Nationwide there was little sympathy for those who refused to serve in the military. Roland was not unlike thousands of other young Americans (many of them Mennonites) whose religious beliefs required them to make such a momentous, deeply unpopular decision. The movie Hacksaw Ridge offers a surprisingly candid and sympathetic portrait of one such young man. Taking a stand as a pacifist in World War II brought social ostracism and disdain, and often much worse. But because of the 19th-century mass migration of Mennonites to Marion County where Goessel is located, the Mennonite population there was still so large that the atmosphere was not as hostile. When the county draft board saw that a registrant was a member of the Mennonite church, conscientious objector status was virtually automatic.

During the Second World War, over 15 million men and women had been called up for service. This amounted to almost 20% of the work force and agriculture was hit particularly hard. Congress reacted by passing legislation allowing for draft deferments for those who were “necessary and regularly engaged in an agricultural occupation.” Roland received just such a deferment and for the next 7 years worked in tandem with his father on the family farm. Then, in 1951 at age 25, Roland went to college.

When I asked Roland what motivated this life-changing decision, he told me,

"I believe that all those years I was always thinking, well, maybe [farming] isn't really what I want to do. And I had this notion that it would be a great thing to go to college and become a teacher, but I didn't know what I wanted to teach. But the idea of teaching was interesting to me. And so finally, after those seven years, I decided, well, if I'm ever gonna make the break, now is the time."

Bethel College today.

Bethel College is located in North Newton, just across the railroad tracks from Newton itself. It is about 20 miles distant from the Duerksen farm. Bethel College, a four-year, private, liberal arts college, is the oldest Mennonite college in North America. Its charter was filed in 1887 by the early central Kansas immigrants because of their commitment, shared with their non-Mennonite neighbours, to educating their children. According to its values statement, “the vision and mission of Bethel College are grounded in the values inherited from its historical relationship with the Christian faith tradition of the Mennonite Church…”

In our lives, there are sometimes special teachers, people who change the course of our lives. For me, one of those teachers was Professor Kenneth Graham of the University of Guelph. Much like Roland, when I went to University I was unsure of my direction. Ken Graham kindled a passion for literature in me that has burned brightly all my life; it was Ken’s unbridled enthusiasm that sealed the deal.

For Roland, the person who filled this mentoring role was Professor Honora Becker. Teaching at a small college meant specialization was out of the question for teachers like Becker. But according to Roland,

“The reason I chose English, I think, was because there was one very enthusiastic teacher. She had to teach so many different courses that she couldn't be a scholar, but it was the fact of her enthusiasm about English literature that influenced me to take it as a major.”

One thing I learned about Roland through our conversations is that once fired up, there is not much that can hold him back. A late starter at college, he wasted little time and completed a four-year honours degree in three years, graduating in 1954.

Not long after Roland's graduation, the military came calling again. In the aftermath of the Second World War, the US government passed the Selective Service Act of 1948 which applied to all men between 21 and 29. A million and a half men were drafted to meet the demands of the Korean War, but even after its conclusion in 1953, the armed forces continued to call up young men. Roland was one of them. Still a conscientious objector, Roland was granted alternative service and performed it through the auspices of the renowned Mennonite Central Committee, headquartered in Akron, Pennsylvania. For two years he worked as a personnel recruiter and publicity writer for three small psychiatric hospitals operated by the Central Committee.

Mary and Roland, 2016

Just before leaving for Pennsylvania, Roland met Mary Ellen Moyer, a Bethel graduate who was teaching school in Hutchinson, Kansas, and courted her through occasional visits. They married in 1955. They are still happily together more than 62 years later.

Once his alternative service was completed in the spring of 1956, Roland immediately enrolled in the English literature programme at Indiana University in Bloomington. He completed his Masters degree over the course of three successive summers, during which time he taught English at a junior high school in Topeka, Kansas. While at Indiana University, Roland studied under another inspirational teacher named Russel Noyes. Through Professor Noyes, Roland first meaningfully encountered the writings of Percy Bysshe Shelley.

Born in 1901, Russell Noyes was a fixture at the Indiana University for most of his career. A committee under his chairmanship had been responsible for the foundation of the Indiana University Press. Roland arrived shortly after Noyes had given up the position of Department Chair, a role he had occupied for 10 years. Though best known for his work on Wordsworth, Noyes had eclectic interests. The two devotions of his life, his love for landscape and his love for the poetry of William Wordsworth, were "fostered in my youth spent among the White Mountains of New Hampshire," Noyes once wrote. He lived a full and satisfying life, dying in 1980. His colleagues remembered him for his belief “in plain living and high thinking and in the value of good letters and their power to ennoble and sustain.” Frankly, he sounds a lot like Roland to me! Read the University's Memorial Resolution, which discusses the life and thought of Russell Noyes, here.

A screen capture of the cover of Noyes' 1956 masterwork.

In the summer of 1956, the year Roland arrived, Noyes was basking in the afterglow of a considerable publishing achievement: Oxford’s then-definitive compendium, “English Romantic Poetry and Prose.” It is a volume that inspired generations of students and was not easily superseded. What set the volume apart was its carefully curated selection of minor poetry, which functioned as a background for the major works normally featured in such anthologies. It also contained a wide selection of Shelley's radical poetry, a body of writing that had long been excluded from anthologies on political grounds. I think this is important for our story.

Both Noyes and his anthology would play a significant role in the development of Roland’s passion for Shelley. One of the first classes Roland took at Indiana was taught by Noyes, with the professor’s new compendium of English Romantics as the textbook. Then in the fall of 1958, Roland entered the PhD programme at Indiana with Noyes serving as his advisor. When I asked Duerksen how he first came into contact with Shelley he told me:

"My very first contact was at Bethel College ... and it was in a survey course that I read some of his poetry. I think I was of course aware even before that of a poem like "Ode to the West Wind" which I probably read in high school. But ... I didn't at that point know enough about him to get excited about him. I did think though that, yes, he was an interesting poet. However, in graduate school, the very first course that I took was a course from Russel Noyes and that's where I became excited about him - and I'll add that Noyes had selected very well for his anthology. It contained some prose and all the good, really great poems of Shelley's."

In the late 1950’s, Shelley’s reputation had reached perhaps its lowest ebb. Sustained attacks by the New Critics (such as TS Eliot and FR Leavis) had followed decades of misinterpretation by Victorians such as Matthew Arnold and Francis Thompson. The Victorians had tried to suppress the political and intellectual sides of Shelley's writing. As Professor Tom Mole has pointed out in his book, What the Victorians Made of Romanticism, anthologies from this period featured only snippets of his poetry, and editors generally avoided including Shelley's most political writings. Duerksen himself later wrote a pioneering book on Victorian attitudes to Shelley.

Roland himself felt some censure from colleagues as his interest in Shelley grew. As he told me, “The old Matthew Arnold judgment on him had simply not gone away: 'A beautiful, ineffectual angel beating in the void his luminous wings in vain.'” Indeed it had not. Seizing on the Shelley they encountered in the Victorian anthologies and either too lazy or indifferent to dig deeper, critics such as Eliot and Leavis savaged Shelley as a superficial lyric poet.

Roland quickly became interested in Shelley, and his political writings in particular. When we regard the essence of Shelley’s political philosophy – for example, his astonishing avowal of the idea of non-violent protest – I think we can also see how Shelley's writings would have dovetailed with the teachings of Roland’s Mennonite ancestors. The core tenets of Mennonite faith are worth requoting: "Mennonites believe in service to others; concern for those less fortunate; involvement in issues of social justice; and emphasis on peaceful, nonviolent resolution of community, national and international conflicts." If we insert “Shelley” for "Mennonite" in the foregoing passage, I think we can see how Roland's upbringing in a community valuing non-conformity, freedom of conscience, and non-violence might have led Roland to feel at home with Shelley.

However, as we know, a striking feature of Shelley’s philosophy was his atheism. Now, there have been those who have disputed this. Certainly, the Victorians fell over backwards to see him as a kind of closet Christian. More modern critics (perhaps missing Shelley’s penchant ironic inversions) have pointed to what they see as overtly religious elements in poems such as Prometheus Unbound. I have written about this at length in my article "I am a lover of humanity, a democrat and an atheist: What did Shelley Mean?". If we were to say Shelley was opposed to organized religion, however, I do not think we would get too much argument today.

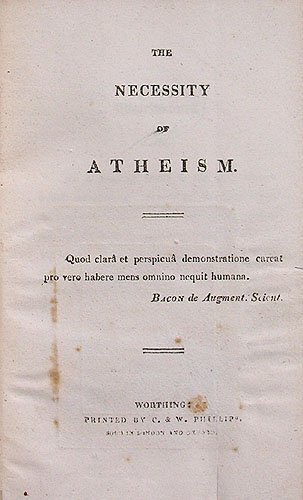

One might think this would pose a problem for Duerksen. However, remember that the central focus of the Mennonite Church is on the teaching of Jesus – and in particular the Sermon on the Mount. As for Shelley, the author of “The Necessity of Atheism” and whose famous declaration “I am a lover of humanity, a democrat and an atheist” (written in a hotel register in Chamonix) made him infamous? Well, Shelley always had a place in his philosophy for the teachings of Jesus. He just did not see him as in any way divine. And he believed that the church had perverted his teachings. I think we can see potential resonances here.

Still, I was intrigued by the unlikeliness of the connection. How does a deeply religious young man from a devoutly evangelical family, who grew up without books on a farm, who attended a religious college in a small town in Kansas, find common ground with one of the most radical, revolutionary, anti-religious thinkers of the 19th Century? How does a Mennonite find common ground with the man about whom Karl Marx himself remarked:

"The real difference between Byron and Shelley is this: those who understand and love them rejoice that Byron died at 36. Because if he had lived he would have become a reactionary bourgeois; they grieve that Shelley died at 29 because he was essentially a revolutionist and he would always have been one of the advanced guard of socialism."

So, I asked him!! And here is what he said:

Roland Duerksen after graduation in 1961, at age 35.

“I began to ask questions about [my beliefs]. I must admit I was quite devout in my religion. I [said to myself], okay, if [I’m] gonna believe this, I ought to really be consistent in every way. The questions I asked were very consistent questions. I would credit the asking of questions as the big turning point in my life. During the 10 years of my education, I [ended up] pretty far removed from where I had started. Up until [the time I went to university], I had had asked some questions already on the farm, but nothing that would really challenge my basic beliefs.”

Moving slowly toward secular humanism through his education, Roland had found an affinity with the views of Shelley that superseded earlier religious convictions. Roland graduated in 1961 with a PhD in English Literature. His thesis was focused on Victorian attitudes to Shelley and would eventually form the basis of his landmark book, Shelleyan Ideas in Victorian Literature. This study should be required reading for all students of Shelley.

In Part Two of this feature on Duerksen's life and thought I will focus on his approach to Shelley, his teaching career, activism and retirement, Duerksen remains one of the most important voices in the Shelleyan critical tradition. Stay tuned.

Let Liberty Lead Us; Connecting the Radical Poetry of Cottingham, Eminem and Shelley