Atheist, Lover of Humanity, Democrat

PERCY BYSSHE SHELLEY

Roland Duerksen: A Shelleyan Life

In the early summer of 2017, I received a letter from the daughter of the noted Shelley scholar Roland Duerksen. Susan had read my article “My Father’s Shelley” and it had struck a chord. She wanted to connect me with her father, now 91 years old and living in New Oxford, Ohio. Roland is the author of two noteworthy and important books on Shelley: "Shelleyan Ideas in Victorian Literature" and "Shelley's Poetry of Involvement". His analysis is penetrating and nuanced, the style conversational and accessible. But it is his overall approach which makes him different, it is imbued with a humanity that reflects well both on himself and his subject. This much I knew, but I knew less about the man himself. I was thrilled that Susan had reached out to me, it was a chance to meet one of the great Shelleyans, but I had no idea whatsoever of the magic which lay in wait for me.

In the early summer of 2017, I received a letter from the daughter of the noted Shelley scholar Roland Duerksen. Susan had read my article “My Father’s Shelley” and it had struck a chord. She wanted to connect me with her father, now 91 years old and living in Oxford, Ohio. Roland is the author of two noteworthy and important books on Shelley: Shelleyan Ideas in Victorian Literature and Shelley's Poetry of Involvement. His analysis is penetrating and nuanced, and his style is conversational and accessible. But it is his overall approach that makes him different: Roland's work is imbued with a humanity that reflects well on both himself and his subject. This much I knew, but I knew less about the man himself. I was thrilled that Susan had reached out to me. She offered me a chance to meet one of the great Shelleyans, but I had no idea whatsoever of the magic that lay in wait for me.

Below, I give you a little about the life and thought of Roland Duerksen, which I gathered from him in interviews that took place over a couple of days. In this essay, I want to share Roland's early life story, from his Mennonite rearing in Dust Bowl Kansas to his development into one of the truly great Shelley scholars. In a second essay, which will appear shortly on our website, I will dive into Duerksen's ideas about Shelley and his later life, including his important work as an activist. Stay tuned!

Roland possesses an extraordinary memory and can quote Shelley at length. Though he has been retired for years, his grasp of the nuances of Shelley’s poetry was nothing short of astonishing. He was also an amusing and friendly interlocutor. He has the ability to put one at ease; you feel like you are out on a country porch, chatting with an old friend you have known for years.

Roland Duerksen was born 23 October 1926, just 7 miles from Goessel, Kansas. Goessel is a small farming community that is located almost dead center on the US map. In Goessel you will find, among other things, the Mennonite Heritage and Agricultural Museum, a hint of the community’s religious and farming roots. To get there, one takes Interstate 135 north from Wichita to Newton, before making a quick right on Highway 15. In seven miles you will find yourself in Goessel. The 240-acre family farm can be found two side roads north and four to the east, another seven miles from town.

Alexanderwohl Mennonite Church, Molotschna, Ukraine.

Roland’s ancestors came to this place in 1874, part of a mass migration of Mennonites fleeing persecution in Russia. The history is fascinating. Originally Dutch, the community emigrated in the early 17th century to what was then South Prussia, and then later in the 1820s to Molotschna, Russia (in what is now Ukraine). The Mennonites had been on the move for centuries, persecuted for what were considered to be heretical beliefs. In Russia they were promised exemption from military service, the right to run their own schools, and the ability to self-govern their villages. In the late 19th century, however, Russia decided to revoke all special privileges that had been given to the community. The leaders of the community made a momentous decision: they would take their entire community to the United States of America. Church elders organized an exploratory mission in 1873 to ascertain the available options. After visiting Texas and Kansas, the leaders returned with the recommendation that the community emigrate to Kansas. At the time, the United States was desperate for skilled farming immigrants, and the Mennonites fit the bill. The community quickly set out, eventually settling in Buhler and Goessel, two towns in rural Kansas. In 1874, after a long, arduous trip, Roland's grandfather Johann (then aged 16) reached his new life in the Goessel community. (Read more about this extraordinary migration here.)

Roland Duerksen in 1934 or 35.

During their first 50 or so years in America, the Goessel farmers prospered essentially as they had expected. Life was persecution-free and work was productive. Free to worship as they pleased, the Duerksens attended Alexanderwohl Church (pictured to the right). Originally built in 1886, it was refurbished substantially over the years, but is still there to this day.

Then came the hard times. By the time Roland was 3, the stock market had crashed; before he was 8, the American West was in the grips of the great drought of the 1930s; and as he turned 16, America entered a World War. How does this compare with your youth?

We all know the drought of the 1930s as the “Dust Bowl” because it resulted in immense dust storms, known as “black blizzards,” which wreaked havoc on America's farms. They came in waves, hitting America hard in 1934, 1936, 1939, and 1940.

On 14 April 1935, a mammoth series of these storms struck the American West. They have since come to be known as “Black Sunday.” They were every bit as bad as their name suggests. Associated Press reporter Robert Geiger (famed for having given the Dust Bowl its name) was caught on a highway north of Boise City, Idaho as he raced at 60 miles an hour in a failed attempt to outrun it. He writes of what he saw as follows:

Dust storm approaching Stratford, Texas, 1935

“The Black Sunday event was one of the less frequent but more dramatic storms borne south on polar air originating in Canada. Rising some 8,000 feet into the air, these churning walls of dirt generated massive amounts of static electricity, complete with their own thunder and lightning ... Temperatures plunged 40 degrees along the storm front before the dust hit.”

“A farmer and his two sons during a storm in Cimaron County, Oklahoma April 1936." Arthur Rothstein.

Goessel is located on the edge of where these storms hit hardest, and the bad weather severely impacted the Duerksens. The family, which consisted of Roland, his parents, and three siblings, was very poor; Roland's father often struggled to make his payments on the farm. Unlike so many, however, the family weathered the Great Depression and emerged from the years of hardship in one piece.

The family were devoted Mennonites. Ironically, Roland's childhood faith may have partly inspired his attraction to England's most famous atheist poet (I will return to this idea). Mennonites believe that baptism should result from an informed decision of which only adults are capable; thus the religion tends to stress individual choice and the freedom of conscience in religious and ethical matters. For much of history, this spirit of non-conformity made them a target of persecution within European societies.

Mennonites place the teachings of Jesus, including pacifism, non-violence, and charity, at the heart of their religion. According to Bethel College, a Christian school Duerksen attended, Mennonites base their faith and lifestyle around the following traits: "service to others; concern for those less fortunate; involvement in issues of social justice; and emphasis on peaceful, nonviolent resolution of community, national and international conflicts.” It is this last feature of their belief system that has resulted in Mennonites’ opposition to war and their refusal to serve in the military. The corollary of this passivism is of critical importance, because Mennonites are dedicated to creating a “more just and peaceful society.” Of course, these same values can be found in Shelley's writing, even if Shelley and the Mennonites took very different paths towards them.

In other ways, however, Roland's upbringing hardly seemed calculated to produce a great literary scholar. His mother, who drew on evangelicalism as well as the Mennonite faith, “was opposed to the reading of novels because they do not contain the truth,” Roland says. This meant that as he grew, books were a rarity and the church was central to his existence. Roland attended a one-room school house which had only a few short shelves of books. When I asked him about this, Roland replied,

"I must say my whole introduction to books came much later. I did read some books. I remember Robinson Crusoe and [books like that]. But, it was very sparse and I was figuring, I guess, that I [was destined to] be a farmer. So why should I read a lot?"

The future, however, had something very different in store for Roland Duerksen: Shelley lay in wait…

Roland Duerksen, circa 1948.

Roland attended high school in Goessel, graduated in 1944, and immediately registered as a conscientious objector. The war was reaching a climax; millions of young Americans were enlisted and fighting overseas. Nationwide there was little sympathy for those who refused to serve in the military. Roland was not unlike thousands of other young Americans (many of them Mennonites) whose religious beliefs required them to make such a momentous, deeply unpopular decision. The movie Hacksaw Ridge offers a surprisingly candid and sympathetic portrait of one such young man. Taking a stand as a pacifist in World War II brought social ostracism and disdain, and often much worse. But because of the 19th-century mass migration of Mennonites to Marion County where Goessel is located, the Mennonite population there was still so large that the atmosphere was not as hostile. When the county draft board saw that a registrant was a member of the Mennonite church, conscientious objector status was virtually automatic.

During the Second World War, over 15 million men and women had been called up for service. This amounted to almost 20% of the work force and agriculture was hit particularly hard. Congress reacted by passing legislation allowing for draft deferments for those who were “necessary and regularly engaged in an agricultural occupation.” Roland received just such a deferment and for the next 7 years worked in tandem with his father on the family farm. Then, in 1951 at age 25, Roland went to college.

When I asked Roland what motivated this life-changing decision, he told me,

"I believe that all those years I was always thinking, well, maybe [farming] isn't really what I want to do. And I had this notion that it would be a great thing to go to college and become a teacher, but I didn't know what I wanted to teach. But the idea of teaching was interesting to me. And so finally, after those seven years, I decided, well, if I'm ever gonna make the break, now is the time."

Bethel College today.

Bethel College is located in North Newton, just across the railroad tracks from Newton itself. It is about 20 miles distant from the Duerksen farm. Bethel College, a four-year, private, liberal arts college, is the oldest Mennonite college in North America. Its charter was filed in 1887 by the early central Kansas immigrants because of their commitment, shared with their non-Mennonite neighbours, to educating their children. According to its values statement, “the vision and mission of Bethel College are grounded in the values inherited from its historical relationship with the Christian faith tradition of the Mennonite Church…”

In our lives, there are sometimes special teachers, people who change the course of our lives. For me, one of those teachers was Professor Kenneth Graham of the University of Guelph. Much like Roland, when I went to University I was unsure of my direction. Ken Graham kindled a passion for literature in me that has burned brightly all my life; it was Ken’s unbridled enthusiasm that sealed the deal.

For Roland, the person who filled this mentoring role was Professor Honora Becker. Teaching at a small college meant specialization was out of the question for teachers like Becker. But according to Roland,

“The reason I chose English, I think, was because there was one very enthusiastic teacher. She had to teach so many different courses that she couldn't be a scholar, but it was the fact of her enthusiasm about English literature that influenced me to take it as a major.”

One thing I learned about Roland through our conversations is that once fired up, there is not much that can hold him back. A late starter at college, he wasted little time and completed a four-year honours degree in three years, graduating in 1954.

Not long after Roland's graduation, the military came calling again. In the aftermath of the Second World War, the US government passed the Selective Service Act of 1948 which applied to all men between 21 and 29. A million and a half men were drafted to meet the demands of the Korean War, but even after its conclusion in 1953, the armed forces continued to call up young men. Roland was one of them. Still a conscientious objector, Roland was granted alternative service and performed it through the auspices of the renowned Mennonite Central Committee, headquartered in Akron, Pennsylvania. For two years he worked as a personnel recruiter and publicity writer for three small psychiatric hospitals operated by the Central Committee.

Mary and Roland, 2016

Just before leaving for Pennsylvania, Roland met Mary Ellen Moyer, a Bethel graduate who was teaching school in Hutchinson, Kansas, and courted her through occasional visits. They married in 1955. They are still happily together more than 62 years later.

Once his alternative service was completed in the spring of 1956, Roland immediately enrolled in the English literature programme at Indiana University in Bloomington. He completed his Masters degree over the course of three successive summers, during which time he taught English at a junior high school in Topeka, Kansas. While at Indiana University, Roland studied under another inspirational teacher named Russel Noyes. Through Professor Noyes, Roland first meaningfully encountered the writings of Percy Bysshe Shelley.

Born in 1901, Russell Noyes was a fixture at the Indiana University for most of his career. A committee under his chairmanship had been responsible for the foundation of the Indiana University Press. Roland arrived shortly after Noyes had given up the position of Department Chair, a role he had occupied for 10 years. Though best known for his work on Wordsworth, Noyes had eclectic interests. The two devotions of his life, his love for landscape and his love for the poetry of William Wordsworth, were "fostered in my youth spent among the White Mountains of New Hampshire," Noyes once wrote. He lived a full and satisfying life, dying in 1980. His colleagues remembered him for his belief “in plain living and high thinking and in the value of good letters and their power to ennoble and sustain.” Frankly, he sounds a lot like Roland to me! Read the University's Memorial Resolution, which discusses the life and thought of Russell Noyes, here.

A screen capture of the cover of Noyes' 1956 masterwork.

In the summer of 1956, the year Roland arrived, Noyes was basking in the afterglow of a considerable publishing achievement: Oxford’s then-definitive compendium, “English Romantic Poetry and Prose.” It is a volume that inspired generations of students and was not easily superseded. What set the volume apart was its carefully curated selection of minor poetry, which functioned as a background for the major works normally featured in such anthologies. It also contained a wide selection of Shelley's radical poetry, a body of writing that had long been excluded from anthologies on political grounds. I think this is important for our story.

Both Noyes and his anthology would play a significant role in the development of Roland’s passion for Shelley. One of the first classes Roland took at Indiana was taught by Noyes, with the professor’s new compendium of English Romantics as the textbook. Then in the fall of 1958, Roland entered the PhD programme at Indiana with Noyes serving as his advisor. When I asked Duerksen how he first came into contact with Shelley he told me:

"My very first contact was at Bethel College ... and it was in a survey course that I read some of his poetry. I think I was of course aware even before that of a poem like "Ode to the West Wind" which I probably read in high school. But ... I didn't at that point know enough about him to get excited about him. I did think though that, yes, he was an interesting poet. However, in graduate school, the very first course that I took was a course from Russel Noyes and that's where I became excited about him - and I'll add that Noyes had selected very well for his anthology. It contained some prose and all the good, really great poems of Shelley's."

In the late 1950’s, Shelley’s reputation had reached perhaps its lowest ebb. Sustained attacks by the New Critics (such as TS Eliot and FR Leavis) had followed decades of misinterpretation by Victorians such as Matthew Arnold and Francis Thompson. The Victorians had tried to suppress the political and intellectual sides of Shelley's writing. As Professor Tom Mole has pointed out in his book, What the Victorians Made of Romanticism, anthologies from this period featured only snippets of his poetry, and editors generally avoided including Shelley's most political writings. Duerksen himself later wrote a pioneering book on Victorian attitudes to Shelley.

Roland himself felt some censure from colleagues as his interest in Shelley grew. As he told me, “The old Matthew Arnold judgment on him had simply not gone away: 'A beautiful, ineffectual angel beating in the void his luminous wings in vain.'” Indeed it had not. Seizing on the Shelley they encountered in the Victorian anthologies and either too lazy or indifferent to dig deeper, critics such as Eliot and Leavis savaged Shelley as a superficial lyric poet.

Roland quickly became interested in Shelley, and his political writings in particular. When we regard the essence of Shelley’s political philosophy – for example, his astonishing avowal of the idea of non-violent protest – I think we can also see how Shelley's writings would have dovetailed with the teachings of Roland’s Mennonite ancestors. The core tenets of Mennonite faith are worth requoting: "Mennonites believe in service to others; concern for those less fortunate; involvement in issues of social justice; and emphasis on peaceful, nonviolent resolution of community, national and international conflicts." If we insert “Shelley” for "Mennonite" in the foregoing passage, I think we can see how Roland's upbringing in a community valuing non-conformity, freedom of conscience, and non-violence might have led Roland to feel at home with Shelley.

However, as we know, a striking feature of Shelley’s philosophy was his atheism. Now, there have been those who have disputed this. Certainly, the Victorians fell over backwards to see him as a kind of closet Christian. More modern critics (perhaps missing Shelley’s penchant ironic inversions) have pointed to what they see as overtly religious elements in poems such as Prometheus Unbound. I have written about this at length in my article "I am a lover of humanity, a democrat and an atheist: What did Shelley Mean?". If we were to say Shelley was opposed to organized religion, however, I do not think we would get too much argument today.

One might think this would pose a problem for Duerksen. However, remember that the central focus of the Mennonite Church is on the teaching of Jesus – and in particular the Sermon on the Mount. As for Shelley, the author of “The Necessity of Atheism” and whose famous declaration “I am a lover of humanity, a democrat and an atheist” (written in a hotel register in Chamonix) made him infamous? Well, Shelley always had a place in his philosophy for the teachings of Jesus. He just did not see him as in any way divine. And he believed that the church had perverted his teachings. I think we can see potential resonances here.

Still, I was intrigued by the unlikeliness of the connection. How does a deeply religious young man from a devoutly evangelical family, who grew up without books on a farm, who attended a religious college in a small town in Kansas, find common ground with one of the most radical, revolutionary, anti-religious thinkers of the 19th Century? How does a Mennonite find common ground with the man about whom Karl Marx himself remarked:

"The real difference between Byron and Shelley is this: those who understand and love them rejoice that Byron died at 36. Because if he had lived he would have become a reactionary bourgeois; they grieve that Shelley died at 29 because he was essentially a revolutionist and he would always have been one of the advanced guard of socialism."

So, I asked him!! And here is what he said:

Roland Duerksen after graduation in 1961, at age 35.

“I began to ask questions about [my beliefs]. I must admit I was quite devout in my religion. I [said to myself], okay, if [I’m] gonna believe this, I ought to really be consistent in every way. The questions I asked were very consistent questions. I would credit the asking of questions as the big turning point in my life. During the 10 years of my education, I [ended up] pretty far removed from where I had started. Up until [the time I went to university], I had had asked some questions already on the farm, but nothing that would really challenge my basic beliefs.”

Moving slowly toward secular humanism through his education, Roland had found an affinity with the views of Shelley that superseded earlier religious convictions. Roland graduated in 1961 with a PhD in English Literature. His thesis was focused on Victorian attitudes to Shelley and would eventually form the basis of his landmark book, Shelleyan Ideas in Victorian Literature. This study should be required reading for all students of Shelley.

In Part Two of this feature on Duerksen's life and thought I will focus on his approach to Shelley, his teaching career, activism and retirement, Duerksen remains one of the most important voices in the Shelleyan critical tradition. Stay tuned.

"I am a Lover of Humanity, a Democrat and an Atheist.” What did Shelley Mean?

The "catch phrase" I have used for the Shelley section of my blog ("Atheist. Lover of Humanity. Democrat.") may require some explanation. The words originated with Shelley himself, but when did he write it, where did he write it and most important why did he write it. Many people have sought to diminish the importance of these words and the circumstances under which they were written. Some modern scholars have even ridiculed him. I think his choice of words was very deliberate and central to how he defined himself and how wanted the world to think of him. They may well have been the words he was most famous (or infamous) for in his lifetime.Five explosive little words that harbour a universe of meaning and significance.

Part of a new feature at www.grahamhenderson.ca is my "Throwback Thursdays". Going back to articles from the past that were favourites or perhaps overlooked. This was my first article for this site and it was published at a time when the Shelley Nation was in its infancy. I have noted how few folks have had a chance to have a look at it. And so I am taking this opportunity to take it out for another spin. If you have seen it, why not share it, if you have not seen it, I hope you enjoy it!

The "catch phrase" I have used for the Shelley section of my blog ("Atheist. Lover of Humanity. Democrat.") may require some explanation. The words originated with Shelley himself, but when did he write it, where did he write it and most important why did he write it. Many people have sought to diminish the importance of these words and the circumstances under which they were written. Some modern scholars have even ridiculed him. I think his choice of words was very deliberate and central to how he defined himself and how wanted the world to think of him. They may well have been the words he was most famous (or infamous) for in his lifetime.

Shelley’s atheism and his political philosophy were at the heart of his poetry and his revolutionary agenda (yes, he had one). Our understanding of Shelley is impoverished to the extent we ignore or diminish its importance.

Shelley visited the Chamonix Valley at the base of Mont Blanc in July of 1816.

"The Priory" Gabriel Charton, Chamonix, 1821

Mont Blanc was a routine stop on the so-called “Grand Tour.” In fact, so many people visited it, that you will find Shelley in his letters bemoaning the fact that the area was "overrun by tourists." With the Napoleonic wars only just at an end, English tourists were again flooding the continent. While in Chamonix, many would have stayed at the famous Hotel de Villes de Londres, as did Shelley. As today, the lodges and guest houses of those days maintained a “visitor’s register”; unlike today those registers would have contained the names of a virtual who’s who of upper class society. Ryan Air was not flying English punters in for day visits. What you wrote in such a register was guaranteed to be read by literate, well connected aristocrats - even if you penned your entry in Greek – as Shelley did.

The words Shelley wrote in the register of the Hotel de Villes de Londres (under the heading "Occupation") were (as translated by PMS Dawson): “philanthropist, an utter democrat, and an atheist”. The words were, as I say, written in Greek. The Greek word he used for philanthropist was "philanthropos tropos." The origin of the word and its connection to Shelley is very interesting. Its first use appears in Aeschylus’ “Prometheus Bound” the Greek play which Shelley was “answering” with his masterpiece, Prometheus Unbound. Aeschylus used his newly coined word “philanthropos tropos” (humanity loving) to describe Prometheus. The word was picked up by Plato and came to be much commented upon, including by Bacon, one of Shelley’s favourite authors. Bacon considered philanthropy to be synonymous with "goodness", which he connected with Aristotle’s idea of “virtue”.

What do the words Shelley chose mean and why is it important? First of all, most people today would shrug at his self-description. Today, most people share democratic values and they live in a secular society where even in America as many as one in five people are unaffiliated with a religion; so claiming to be an atheist is not exactly controversial today. As for philanthropy, well, who doesn’t give money to charity, and in our modern society, the word philanthropy has been reduced to this connotation. I suppose many people would assume that things might have been a bit different in Shelley’s time – but how controversial could it be to describe yourself in such a manner? Context, it turns out, is everything. In his time, Shelley’s chosen labels shocked and scandalized society and I believe they were designed to do just that. Because in 1816, the words "philanthropist, democrat and atheist" were fighting words.

Shelley would have understood the potential audience for his words, and it is therefore impossible not to conclude that Shelley was being deliberately provocative. In the words of P.M.S. Dawson, he was “nailing his colours to the mast-head”. As we shall see, he even had a particular target in mind: none other than Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Word of the note spread quickly throughout England. It was not the only visitor’s book in which Shelley made such an entry. It was made in at least two or three other places. His friend Byron, following behind him on his travels, was so concerned about the potential harm this statement might do, that he actually made efforts to scribble out Shelley’s name in one of the registers.

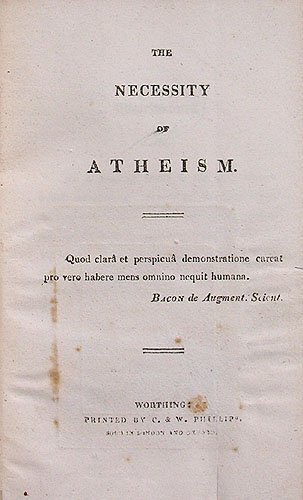

While Shelley was not a household name in England, he was the son of an aristocrat whose patron was one of the leading Whigs of his generation, Lord Norfolk. Behaviour such as this was bound to and did attract attention. Many would also have remembered that Shelley had been actually expelled from Oxford for publishing a notoriously atheistical tract, The Necessity of Atheism.

Shelley's pamphlet, "The Necessity of Atheism"

While his claim to be an atheist attracted most of the attention, the other two terms were freighted as well. Democrat then had the connotations it does today but such connotations in his day were clearly inflammatory (the word “utter” acting as an exclamation mark). The term philanthropist is more interesting because at that time it did not merely connote donating money, it had overt political and even revolutionary overtones. To be an atheist or a philanthropist or a democrat, and Shelley was all three, was to be fundamentally opposed to the ruling order and Shelley wanted the world to know it.

What made Shelley’s atheism even more likely to occasion outrage was the fact that English tourists went to Mont Blanc specifically to have a religious experience occasioned by their experience of the “sublime.” Indeed, Timothy Webb speculates that at least one of Shelley’s entries might have been in response to another comment in the register which read, “Such scenes as these inspires, then, more forcibly, the love of God”. If not in answer to this, then most certainly Shelley was responding to Coleridge, who, in his head note to “Hymn Before Sunrise, in the Vale of Chamouni,” had famously asked, “Who would be, who could be an Atheist in this valley of wonders?" In a nutshell Shelley's answers was: "I could!!!"

Mont Blanc, 16 May 2016, Graham Henderson

The reaction to Shelley’s entry was predictably furious and focused almost exclusively on Shelley’s choice of the word “atheist”. For example, this anonymous comment appeared in the London Chronicle:

Mr. Shelley is understood to be the person who, after gazing on Mont Blanc, registered himself in the album as Percy Bysshe Shelley, Atheist; which gross and cheap bravado he, with the natural tact of the new school, took for a display of philosophic courage; and his obscure muse has been since constantly spreading all her foulness of those doctrines which a decent infidel would treat with respect and in which the wise and honourable have in all ages found the perfection of wisdom and virtue.

Shelley’s decision to write the inscription in Greek was even more provocative because as Webb points out, Greek was associated with “the language of intellectual liberty, the language of those courageous philosophers who had defied political and religious tyranny in their allegiance to the truth."

The concept of the “sublime” was one of the dominant (and popular) subjects of the early 19th Century. It was widely believed that the natural sublime could provoke a religious experience and confirmation of the existence of the deity. This was a problem for Shelley because he believed that religion was the principle prop for the ruling (tyrannical) political order. As Cian Duffy in Shelley and the Revolutionary Sublime has suggested, Prometheus Unbound, like much of his other work, “was concerned to revise the standard, pious or theistic configuration of that discourse [on the natural sublime] along secular and politically progressive lines...." Shelley believed that the key to this lay in the cultivation of the imagination. An individual possessed of an “uncultivated” imagination, would contemplate the natural sublime in a situation such as Chamonix Valley, would see god at work, and this would then lead inevitably to the "falsehoods of religious systems." In Queen Mab, Shelley called this the "deifying" response and believed it was an error that resulted from the failure to 'rightly' feel the 'mystery' of natural 'grandeur':

"The plurality of worlds, the indefinite immensity of the universe is a most awful subject of contemplation. He who rightly feels its mystery and grandeur is in no danger of seductions from the falsehoods of religious systems or of deifying the principle of the universe” (Queen Mab. Notes, Poetical Works of Shelley, 801).

He believed that a cultivated imagination would not make this error.

This view was not new to Shelley, it was shared, for example, by Archibald Alison whose 1790 Essays on the Nature and Principles of Taste made the point that people tended to "lose themselves" in the presence of the sublime. He concluded, "this involuntary and unreflective activity of the imagination leads intentionally and unavoidably to an intuition of God's presence in Creation". Shelley believed this himself and theorized explicitly that it was the uncultivated imagination that enacted what he called this "vulgar mistake." This theory comes to full fruition in Act III of Prometheus Unbound where, as Duffy notes,

“…their [Demogorgon and Asia] encounter restates the foundational premise of Shelley’s engagement with the discourse on the natural sublime: the idea that natural grandeur, correctly interpreted by the ‘cultivated imagination, can teach the mind politically potent truths, truths that expose the artificiality of the current social order and provide the blueprint for a ‘prosperous’, philanthropic reform of ‘political institutions’.

Shelley’s atheism was thus connected to his theory of the imagination and we can now understand why his “rewriting” of the natural sublime was so important to him.

If Shelley was simply a non-believer, this would be bad enough, but as he stated in the visitor’s register he was also a “democrat;” and by democrat Shelley really meant republican and modern analysts have now actually placed him within the radical tradition of philosophical anarchism. Shelley made part of this explicit when he wrote to Elizabeth Hitchener stating,

“It is this empire of terror which is established by Religion, Monarchy is its prototype, Aristocracy may be regarded as symbolizing its very essence. They are mixed – one can now scarce be distinguished from the other” (Letters of Shelley, 126).

This point is made again in Queen Mab where Shelley asserts that the anthropomorphic god of Christianity is the “the prototype of human misrule” (Queen Mab, Canto VI, l.105, Poetical Works of Shelley, 785) and the spiritual image of monarchical despotism. In his book Romantic Atheism, Martin Priestman points out that the corrupt emperor in Laon and Cythna is consistently enabled by equally corrupt priests. As Paul Foot avers in Red Shelley, "Established religions, Shelley noted, had always been a friend to tyranny”. Dawson for his part suggests, “The only thing worse than being a republican was being an atheist, and Shelley was that too; indeed, his atheism was intimately connected with his political revolt”.

Three explosive little words that harbour a universe of meaning and significance.

- Aeschylus

- Amelia Curran

- Anna Mercer

- Arethusa

- Arielle Cottingham

- Atheism

- Byron

- Charles I

- Chartism

- Cian Duffy

- Claire Clairmont

- Coleridge

- Defense of Poetry

- Diderot

- Douglas Booth

- Earl Wasserman

- Edward Aveling

- Edward Silsbee

- Edward Trelawny

- Edward Williams

- England in 1819

- Engles

- Francis Thompson

- Frank Allaun

- Frankenstein

- Friedrich Engels

- George Bernard Shaw

- Gerald Hogle

- Harold Bloom

- Henry Salt

- Honora Becker

- Hotel de Villes de Londres

- Humanism

- James Bieri

- Jeremy Corbyn

- Karl Marx

- Kathleen Raine

- Keats-Shelley Association

- Kenneth Graham

- Kenneth Neill Cameron

- La Spezia

- Larry Henderson

- Leslie Preger

- Lucretius

- Lynn Shepherd

- Mark Summers

- Martin Priestman

- Marx

- Marxism

- Mary Shelley

- Mary Sherwood

- Mask of Anarchy

- Michael Demson

- Michael Gamer

- Michael O'Neill

- Michael Scrivener

- Milton Wilson

- Mont Blanc

- Neccessity of Atheism

- Nora Crook

- Ode to the West Wind

- Ozymandias

- Paul Foot

- Paul Stephens

- Pauline Newman

- Percy Shelley

- Peter Bell the Third

- Peterloo

- Philanthropist

- philanthropos tropos

- PMS Dawson

- Political Philosophy

- Prince Athanese

- Prometheus Unbound

- Queen Mab

- Richard Holmes

- romantic poetry

- Ross Wilson

- Sandy Grant

- Sara Coleridge

- Sarah Trimmer

- Scientific Socialism

- Shelleyana

- Skepticism

- Socialism

- Song to the Men of England

- Stopford Brooke

- Tess Martin

- The Cenci

- The Mask of Anarchy

- The Red Shelley

- Timothy Webb

- Tom Mole

- Triumph of Life

- Victorian Morality

- Villa Diodati

- William Godwin

- William Michael Rossetti

- Wordsworth

- Yvonne Kapp