Atheist, Lover of Humanity, Democrat

PERCY BYSSHE SHELLEY

Eleanor Marx Battles the Shelley Society!

In April of 1888, Eleanor Marx and Edward Aveling delivered a Marxist evaluation of the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley to an institution known as “The Shelley Society”. Composed of some of the giants of the Victorian literary community, the Society undertook research, hosted speeches, spawned local affiliates, republished important articles and poems (some for the first time!) and even produced Shelley’s The Cenci for the stage. But the Shelley Society was also a vehicle seemingly designed to obliterate Shelley’s left-wing politics. This article examines why the Shelley Society came into being and how it influenced the reception of Shelley for generations to come. Go behind the scenes with me as Eleanor Marx battles the forces of the male, bourgeois, Victorian literary establishment.

Eleanor Marx Battles the Shelley Society!

Eleanor Marx

In 1886, at the height of the Victorian era, a group of admirers of Percy Bysshe Shelley came together to form the Shelley Society. Among the founders were some of the intellectual giants of the age. For example, the list of distinguished names includes Edward Dowden, Buxton Forman, William Michael Rossetti, Arthur Napier (the Merton Professor of English Language and Literature at Oxford), Dr. Richard Garnett, George Bernard Shaw, Henry Salt, William Bell Scott (whose gorgeous painting of Shelley’s grave hangs in the Ashmolean Museum), Algernon Charles Swinburne, Francis Thompson, the Rev. Stopford Brooke, Edward Aveling and Eleanor Marx - to name only a few. At inception there were just over 100 but this number soon swelled to over 400 members. In addition, members of the general public were allowed to attend the meetings. As a result, while the inaugural lecture had an audience of over 500 - only a small proportion of whom were actual paid members. As it grew, the Society came to have chapters around the world. One thing that to me stands out from the list of eminent names, is what amounts to an ideological left/right fault-line which is at the heart of our story. And it actually speaks to Shelley’s protean character that he would find passionate adherents on both ends of the political spectrum.

A useful history of the literary societies of the 1880s (Shelley’s was not the only one) can be found in Angela Dunstan’s article, ‘The Newest Culte’: Victorian Poetry and the Literary Societies of the 1880s (In Nineteenth-Century Literature in Transition: The 1880s, edited by Penny Fielding and Andrew Taylor and published in 2019 by Cambridge). Dunstan points out that

“Though many in the Society were eminent literary scholars or critics the Notebooks make a concerted effort to legitimate opinions and close readings of rank and file members, demonstrating the capacity of vernacular poetry to be seriously studied by professional scholars and amateur enthusiasts alike.”

Also apparent to anyone reading through the Society proceedings is the presence of female voices. Dunstan writes,

Women were active in the Shelley society; notices of their involvement were regularly printed in “Ladies’ Columns:” in the press and reprinted in the Notebooks, and female members certainly attended the Society’s activities that contributed to debates. The Notebooks evidence debates over close readings of Alastor, for example, where ordinary female speakers confidently take on George Bernard Shaw or William Michael Rossetti over interpretation, and it is this democratic nature of literary societies’ debates which many outside of the societies and particularly in the universities found threatening.

“A stuffy Victorian, bourgeois morality suffuses the written record of the Society’s meetings.”

The Society published notes of its meeting, undertook research, hosted speeches, spawned local affiliates, republished important articles and poems (some for the first time!) and even produced Shelley’s The Cenci for the stage — all before it fell apart four years later. The goal was to make the scholarly study of Shelley more accessible to the general public - to in effect popularize Shelley and “democratise” literary criticism - and the meetings gained a reputation for an interest in critical rather than mere biographical exercises. Though largely forgotten by history, the proceedings of the Shelley Society constituted a momentous episode in the history of Shelley’s reception by the reading public; though one that is not without controversy.

Some, notably the socialist Paul Foot, were of the view that the Society had a deleterious effect on his reputation as a political radical. That said, Professor Alan Weinberg has noted that

We are reminded that prominent members of the Shelley Society present at the inaugural lecture were not averse to the poet's politics. If anything they tended to advance them. Succeeding lectures were devoted to Queen Mab (Forman), Prometheus Unbound(Rossetti), The Triumph of Life (Todhunter), The Mask of Anarchy (Forman), The Hermit of Marlow and Reform (Forman), Shelley and Disraeli's politics (Garnett) -all of which point positively or constructively to Shelley's radical sentiments.

The Rev. Stopford Brooke, 1885

The first speech at the inaugural meeting of the Society was delivered by the Reverend Stopford Augustus Brooke. Brooke was a prominent member of the Church of England who had risen to the post of “chaplain in ordinary” to Queen Victoria in 1875. He was a patron of the arts and was the leading figure in raising the money to acquire Dove Cottage (now administered by the Wordsworth Trust). In 1880, Brooke took the unusual step of seceding from the church because he no longer subscribed to its principal dogmas. In that same year Brooke also published a collection of Shelley’s poetry, Poems from Shelley, selected and arranged by Stopford A. Brooke (London: Macmillan & Co., 1880). In the speech, Brooke principally responds to the attacks on Shelley’s character that had been famously leveled by Mathew Arnold - opinions which have poisoned Shelley’s reception to the present day. The Society, said Brooke, desired to

“connect together all that would throw light on the poet’s personality and his work, to ascertain the truth about him, to issue reprints and above all to do something to further the objects of Shelley’s life and works, and to better understand and love a genius which was ignored and abused in his own time, but which had risen from the grave into which the critics had trampled it to live in the hearts of men.”

Matthew Arnold

Brooke also devoted considerable attention to rebutting the opinions of perhaps Shelley’s most effective critic, Matthew Arnold. Arnold’s judgement on Shelley was, Brooke thought, “victimized by his personal antipathy to Shelley’s idealism”, and Brooke found his views “petulant” and “prejudiced”. While others had attacked Shelley, none of them had the gravitas and influence of Mathew Arnold; Arnold who had characterized Shelley as a “beautiful and ineffectual angel, beating in the void his luminous wings in vain”. Arnold’s critique of Shelley appeared in a pair of essays written on Byron and Shelley and which were published together in his Essays in Criticism, Second Series (1888). You can find a beautifully written, approachable essay on the subject written by Professor Alan Weinberg here. Arnold’s encapsulation of Shelley’s character went on to have enormous influence. Weinberg:

On close examination (as will be shown), his [Arnold’s] argument is grossly superficial and unreliable. What has tended to carry weight is the authority of Arnold's position as eminent critic of his age (while this had currency) and the persuasiveness of his dictum which has connected with an ongoing antipathy or ambivalence towards Shelley. In the course of time, the dictum has become disentangled from the original argument and has acquired a life of its own.

Despite Professor Weinberg’s opinion expressed above, it is my view that Shelley’s radical politics were at best tolerated by Society members. It seems to me that from inception, there was a not so hidden agenda which came to dominate the Society’s proceedings. In seeking the “truth about Shelley”, Brooke for example proposed a distinctly religious and spiritual approach saying that Shelley’s “method was the method of Jesus Christ, reliance on spiritual force only…” Brooke saw Shelley’s life as “full of natural piety” and “noble ideals” while at the same times characterising his “aspirations” as “often unreal and visionary.” He saw Shelley as a man “not content with the world the way as it is” (fair enough) but as a “prophetic singer of the advancing kingdom of faith and hope and love.” (more problematic). A stuffy Victorian bourgeois morality suffuses the written record of the Society’s meetings. That morality even appears to have influenced membership applications. Henry Salt records that when Edward Aveling (a socialist living out of wedlock with the daughter of Karl Marx) attempted to join the Society, his application was turned down by a majority of members - “his marriage relations being similar to Shelley’s”. It was only through the “determined efforts” of William Michael Rossetti that the decision was over-turned (Yvonne Kapp, Eleanor Marx, p 450).

Frederick James Furnivall. William Rothenstein (attributed), Trinity Hall

Frederick James Furnivall, a prominent “Christian Socialist” who founded the London Working Men’s College and was a tireless promoter of English literature, lauded Brooke’s impassioned remarks by declaring that the Shelley Society would devote itself to responding to what he characterized as “Philistine” attacks on Shelley’s character and poetry. The chief “Philistine” referenced here was Cordy Jeaffreson who had recently authored a highly critical biography of Shelley: (The Real Shelley: New Views of the Poet's Life, 2 vols. 1885). What we see playing out here was a curious contest between rival camps to stake out exactly who the “real” Shelley was and just importantly, what he believed.

The Society’s goal, then, was not only to rebut attacks of Shelley, but also to find the “real Percy Bysshe Shelley”. Now, this is a mission which frankly resonates with me! However, at the hands of the Society, a very unusual, apolitical, quasi-religious Shelley would emerge as “real” Shelley. For his part, this would probably have come as an enormous surprise to Shelley himself - the self-declared atheist, humanist and republican who once wrote, "I tell of great matters, and I shall go on to free men's minds from the crippling bonds of superstition.” This battle for the soul of the “real” Percy Bysshe Shelley has never really gone away and it had real world consequences for me - something I wrote about in My Father’s Shelley - a Tale of Two Shelleys.

“I tell of great matters, and I shall go on to free men’s minds from the crippling bonds of superstition.”

However, the Society didn’t just want a new, more religiously-minded Shelley, whose “rotten ethics” (see below) had been explained away as youthful folly. Notwithstanding the fact that Society members had a somewhat permissive or indulgent attitude toward Shelley’s radicalism (Weinberg, above), there was nonetheless a distinct tendency to in effect depoliticise Shelley. For example, in a lecture to the Society on 14 April 1886, Buxton Forman complained that,

“Shelley is far more widely known as the author of Queen Mab than as the author of Prometheus Unbound. As the latter really strengthens the spirit while the former does not, we, who reverence Shelley for his spiritual enthusiasm, desire to see all that changed. And the change is advancing.“

The battle lines were clearly drawn. This fight was going to be about more than poetry; it was going to be about politics and it was going to be about class. A major stumbling block for the bourgeois members of the Society was clearly Shelley’s professed atheism. But there were ways to deal with this. Francis Thompson, for example, devoted a significant portion of his famous 1889 essay, Shelley, opining that Shelley could not really have been an atheist - because he was “struggling - blindly, weakly, stumblingly, but still struggling - toward higher things.” He had just died before he got there. While we might question the robustness of this evidence, his final argument was air-tight: “We do not believe that a truly corrupted spirit can write consistently ethereal poetry…The devil can do many things. But the devil cannot write poetry.”

Sara Coleridge daughter of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and an arch, bourgeois Victorian, reflected a widespread view when she wrote to a friend,

Sara Coleridge

"You are more displeased with Shelley's wrong religion than with Keats' no religion. Surely Shelley was as superior to Keats as a moral being, as he was above him in birth and breeding. Compare the letters of the two . . . see how much more spiritual is Shelley's expression, how much more of goodness, of Christian kindness, does his intercourse with his friends evince.”

One might well think that with friends like this, who needs enemies? I am not sure what is worse: the cringe-worthy dismissal of Keats, or the complete misappropriation of Shelley. And indeed, on another occasion one of the attendees said almost exactly that. Having listened to a speech about Shelley by Edward Silsbee that struck her as more of a “homily” than literary criticism, a Mrs. Simpson remarked that had Shelley heard the speech, he might well have said, “Save me from my friends.” Silsbee was reminded by another listener that between Dante and Shelley there was in fact another poet by the name of Shakespeare. Hagiography was very much the order of the day it would appear.

By the time the bourgeois members of the Shelley Society had finished with Shelley, poems like Queen Mab had been successfully relegated to the back pages of collected editions under the heading “Juvenilia“ - a designation suggested by Forman himself. Thus a cordon sanitaire had been established - Shelley’s radicalism was “ring-fenced”. He had in effect been reclaimed by proper society.

“The battle lines were clearly drawn. This fight was going to be about more than poetry; it was going to be about politics and it was going to be about class. ”

Why was this happening? Well, Shelley an important poet. But he had two very distinct and mutually antagonistic audiences - both loved him and for very different reasons. On the one hand was the working class and its socialist champions. On the other? The upper class who valued above all Shelley’s “spiritualism”, his love poetry and his lyricism. The two could have probably co-existed but for the annoying fact that Shelley himself was ill-fitted to the bourgeois camp. That and the fact Shelley was actually a revolutionary who had set himself implacably against them - most of his output was intensely political and revolutionary.

Karl Marx and his daughters with Engels.

Bourgeois Victorian literary society in the main objected Shelley’s radical heritage. They wanted to shift focus from this unwelcome aspect of his poetry and in this regard, his prose was for the most part ignored. Though perhaps presciently, it was Arnold who observed that Shelley’s letters and essays might better resist the “wear and tear of time” and “finally come to stand higher that his poetry”. Instead the focus was to shift to Shelley’s “mysticism”, his “spiritual enthusiasm” and above all his “lyricism”. Shelley’s political poetry was considered to be almost an aberration and a defect of character and grist for the “street socialists.”

For a glimpse into what they were reacting against, here is the view from the left (seemingly directly in response to the activities of the Shelley Society), courtesy of Friedrich Engels:

"Shelley, the genius, the prophet, finds most of [his] readers in the proletariat; the bourgeoisie own the castrated editions, the family editions cut down in accordance with the hypocritical morality of today.”

According to Eleanor Marx, her father,

“who understood the poets as well as he understood the philosophers and economists, was wont to say: “The real difference between Byron and Shelley is this: those who understand them and love them rejoice that Byron died at thirty-six, because if he had lived he would have become a reactionary bourgeois; they grieve that Shelley died at twenty-nine, because he was essentially a revolutionist, and he would always have been one of the advanced guard of socialism.”

Our story begins in earnest during the spring of 1887 when in a speech to the Society on 13 April one of the members, Alexander G. Ross delivered a bitter, class-based attack not upon Shelley himself, but upon Shelley’s socialist proponents. According to Paul Foot, Ross had been “enraged to discover that workers and even socialists were quoting a well-known English poet to their advantage”. Worse, of course, was the fact that Ross believed that Shelley’s “ethics were rotten.” As did many of his bourgeois colleagues.

“...they grieve that Shelley died at twenty-nine, because he was essentially a revolutionist, and he would always have been one of the advanced guard of socialism.””

Ross approached the issue by arguing that while,

“…no one can contest the right of anyone even though he may be a mere sans culotte who runs about with red rag, to quote Shelley when or where he pleases; but when the blatant and cruel socialism of the street endeavours to use the lofty and sublime socialism of the study for its own base purpose it is time that with no uncertain sound all real lovers of the latter should disembowel any sympathy with the former….It will be clearly understood that I strongly protest against any Imaginative writer being cited as an authority in favour of any political or social action…”

Edward Aveling

The distinction between “parlour socialism” and socialism actually put into action (“street socialism”) is quite something. Poetry was to be for poetry’s sake - and to hell with the politics. Now, in fairness, it is to be pointed out that both Rossetti and Furnivall both objected to elements of Ross’s address. Rossetti noted that a “great poet should put morals into his writings”, while carefully reinterpreting the Revolt of Islam’s message as “do good to your enemies; an annunciation of a universal reign of love.” The Revolt of Islam he concluded was “certainly not a didactic poem”. Furnivall complained that Ross seemed to treat poetry as a “toy”, and averred that “poets were men who felt certain truths more deeply than other men, and it was their work to put forth those thoughts.” Three of the avowed socialists in the room, Henry Salt, Aveling and George Bernard Shaw objected more specifically to the attacks on socialism.

Aveling, for his part, maintained that “the socialism of the study and the street was one and the same thing – and that constituted the beauty of modern socialism.” Shaw was highly critical as well, arguing that “a poem ought to be didactic, and ought to be in the nature of a political treatise - for poetry was the most artistic way of teaching those things a poet ought to teach.” One of the oddities of the debate turns on the argument about whether Shelley’s poetry was “didactic” or not. It will help modern readers if we unpack the coded language here. Opponents of Shelley’s didacticism were really reacting to his politics; or to be more accurate, the fact that socialists were championing him and as Paul Foot suggested, doing so to their advantage - in other words advancing the cause of socialism.

Annie Besant

Ross’s contentious address prompted Aveling and Marx to request an opportunity to present the case for an alternative version of the “Real Shelley”; a case for the “Socialist Shelley”. To them, what was happening in the 1880s was, plainly, a battle for the legacy of Percy Bysshe Shelley. Viewed from the left, the stakes would have been remarkably high. Marx and Aveling saw Shelley as someone who saw more clearly than anyone else “that the epic of the nineteenth century was to be the contest between the possessing and the producing classes.” This insight removed him “from the category of Utopian socialists and [made] him as far as was possible in his time, a socialist of modern days.” To see Shelley “castrated” (in the words of Friedrich Engels) and co-opted by the bourgeoisie was a call to arms. Aveling delivered the paper in April of 1888 though was careful to point out that “although I am the reader, it must be understood that I am reading the work of my wife as well as, no, more than, myself.”

Eleanor Marx was an extraordinary person who deserves far more attention from our modern society. According to Harrison Fluss and Sam Miller writing in Jacobin, Marx was

born on January 16, 1855, Eleanor Marx was Karl and Jenny Marx’s youngest daughter. She would become the forerunner of socialist feminism and one of the most prominent political leaders and union organizers in Britain. Eleanor pursued her activism fearlessly, captivated crowds with her speeches, stayed loyal to comrades and family, and grew into a brilliant political theorist. Not only that, she was a fierce advocate for children, a famous translator of European literature, a lifelong student of Shakespeare and a passionate actress.

To which we can add that she was also devotee of and influenced by Percy Shelley. Both Eleanor and Aveling were immersed in culture - much like Karl Marx himself. This was not Aveling’s first foray into the subject matter. In 1879 he had given a speech about Shelley to the Secular Society - described by Annie Besant as a “simple, loving, and personal account of the life and poetry of the hero of the free thinkers..” (Kapp, p. 451) This assessment, by the way, is yet another indication of the high regard accorded to Shelley by the socialist community. According to her Wikipedia entry, Besant was was a

“British socialist, theosophist, women's rights activist, writer, orator, educationist, and philanthropist. Regarded as a champion of human freedom, she was an ardent supporter of both Irish and Indian self-rule. She was a prolific author with over three hundred books and pamphlets to her credit.”

That she considered Shelley to be the “hero of freethinkers” is telling and a further reminder of the influence Shelley had on 19th century socialists. Kapp perceptively points out that:

“There can be no doubt that this lecture, though delivered by Aveling, was it to collaboration between two people who had long and devotedly studied the poet with equal enthusiasm, Aveling primarily as an atheist, Eleanor as a revolutionary…”

Eleanor Marx at 18

Marx and Aveling were at pains to point out that “the question to be considered…is not whether socialism is right or wrong, but whether Shelley was or was not a socialist.” Thus they first described a set of six distinguishing hallmarks of socialism and pointed out, “…If he enunciated views such as these, or even approximating to these, it is clear that we must admit that Shelley was a teacher as well as a poet.” The authors then set out their course of study:

(1) A note or two on Shelley himself and his own personality, as bearing on his relations to Socialism;

(2) On those, who, in this connection had most influence upon his thinking;

(3) His attacks on tyranny, and his singing for liberty, in the abstract;

(4) His attacks on tyranny in the concrete;

(5) His clear perception of the class struggle; and

(6) His insight into the real meaning of such words as “freedom,'’ “justice,” “crime,” “labour,” and “property”.

Of Shelley’s personality, Marx and Aveling seem principally interested in adducing (with copious citations from The Cenci, Prince Athanese, Queen Mab, Laon and Cythna and Triumph of Life) Shelley’s connection to the politics of his era, noting his advanced thinking on issues such as Napoleon and evolution:

“Of the two great principles affecting the development of the individual end of the race, those of heredity and adaptation, he had clear perception, although day as yet we are neither accurately defined nor even named. He understood that men and peoples were the result of their ancestry and their environment.”

As for Shelley’s influences, the authors begin by contrasting Shelley with Byron.

In Byron they suggest,

“…we have the vague, generous and genuine aspirations in the abstract, which found their final expression in the bourgeois-democratic movement of 1848. In Shelley, there was more than the vague striving after freedom in the abstract, and therefore his ideas are finding expression in the social-democratic movement of our own day….He saw more clearly than Byron, who seems scarcely to have seen it at all, that the epic of the nineteenth century was to be the contest between the possessing and the producing classes. And it is just this that removes him from the category of Utopian socialists, and makes him so far as it was possible in his time, a socialist of modern days.

They then enumerate those whom they consider his prime influences: François-Noël Baboeuf, Rousseau, the French philosophes, the Encyclopaedists, Baron d’Holbach, and Denis Diderot. The addition of Diderot to this list is interesting. We now know that as early as 1812, Shelley had ordered copies of Diderot’s works - but this was not widely known in the 19th Century. I certainly feel that the spirit of Diderot suffuses Shelley’s philosophy and writings. Interestingly, Aveling and Marx thought very highly of Diderot as well, averring that Diderot “was the intellectual ghost of everybody of his time” - an assessment described to me as a “penetrating insight” by Andrew Curran the author of the excellent Diderot and the Art of Thinking Freely.

“We simply can not underestimate the influence Shelley had on the socialists of this period.”

Godwin was also singled out, hardly surprisingly - though as Marx and Aveling ruefully note, “Dowden’s Life has made us all so thoroughly acquainted with the ill-side of Godwin that just now there may be a not unnatural tendency to forget the best of him.” But of real interest is the time spent adducing the under-appreciated influence of “the two Marys” (Wollstonecraft and Godwin), and the perspective is instructive. “In a word,” Marx and Aveling suggest,

the world in general has treated the relative influences of Godwin on the one hand and of the two women on the other, pretty much has might have been expected with men for historians. Probably the fact that he saw so much through the eyes of these two women quickened Shelley's perception of woman's real position in society and the real cause of that position….this understanding…is in a large measure due to the two Marys.

Shelley’s espousal of what we would now call feminist causes was extremely unusual for his time. Clearly it resonated with Marx and Aveling who comment that “it was one of Shelley's "delusions that are not delusions" that man and women should be equal and united. And Paul Foot seizes on and develops this theme in his speech to the 1981 Marxism Conference in London.

“It’s not just that he saw that women were oppressed in the society, that the women were oppressed in the home; it’s not just that he saw the monstrosity of that. It’s not even just that he saw that there was no prospect whatever of any kind for revolutionary upsurge if men left women behind. Like, for example, in the 1848 rebellions in Paris where he men deliberately locked the women up and told them they couldn’t come out to the demonstrations that took place there because in some way or other that would demean the nature of the revolution. It wasn’t just that he saw the absurdity of situations like that. It was that he saw what happened when women did activate themselves, and did start to take control of their lives, and did start to hit back against repression. Shelley saw that what happened then was that again and again, women seized the leadership of the forces that were in revolution! All through Shelley’s poetry, all his great revolutionary poems, the main agitators, the people that do most of the revolutionary work and who he gives most of the revolutionary speeches, are women. Queen Mab herself, Asia in Prometheus Unbound, Iona in Swellfoot the Tyrant, and most important of all, Cythna in The Revolt of Islam. All these women, throughout his poetry, were the leaders of the revolution and the main agitators.”

I have written myself at length on the fact that much of Shelley’s radicalism concentrates on what he would have considered twinned targets: the monarchy and religion (religion being for Shelley the “hand-maiden of tyranny”). So it is not surprising that when Marx and Aveling came to the third part of their presentation, they pointed out that at the root of Shelley’s antagonism to the tyranny of church and state was the belief that the ultimate problem was

“the superstitious in the capitalistic system in the empire of class…. And always, every word that he has written against religious superstition and the despotism of individual rulers may be read as against economic superstition and the despotism of class.”

They also pointed out the extent to which Shelley’s concern with tyranny was more than just abstract, he is lauded not just for his attention to Mexico, Spain, Ireland and England, but also for his attacks on individuals: Castlereagh, Sidmouth, Eldon and Napoleon. “He is forever,” they wrote, “denouncing priest and king and statesman.”

Of most interest to me is the fourth section in which Marx and Aveling turn to Shelley’s understanding of “class struggle.” What makes Shelley a socialist more than anything else,

“is his singular understanding of the facts that today tyranny resolves itself into the tyranny of the possessing class over the producing, and that to this tyranny in the ultimate analysis is traceable almost all evil and misery. He saw that the soul-called middle class is the real tyrant, the real danger at the present day.”

Shelley by George Clint after Amelia Curran

To support this position, a veritable arsenal of quotations is deployed. From what they call the Philosophic View of Reform, from Godwin, from letters to Hookham and Hitchens, and from Swellfoot the Tyrant, Peter Bell the Third and Charles the I. The effect is spectacular. For example, this from Swellfoot: “Those who consume these fruits through thee [the goddess of famine] grow fat. / Those who produce these fruits through the grow lean". The cumulative effect is to place Shelley in a tradition that leads directly to Marx, Engels and modern socialism. And, indeed, the resonance and reverberation of the language is uncanny.

Marx and Aveling conclude the section by quoting Mary to great effect (from her notes to her collected edition): “He believed the clash between the two classes of society was inevitable, and he eagerly ranged himself on the peoples side.” They clearly see Shelley as a direct precursor to Marx and Engels and it is hard to disagree with them. In an unusual turn of phrase considering their undoubted atheism, they had earlier referred to Shelley as a philosopher and a prophet - a term you will have seen Engels use as well in the quotation cited above. Elsewhere, Marx and Aveling refer to him as the “poet-leader”. In a truly remarkable passage they seem to treat Shelley’s writing, his value system, almost as a “sacred text”:

This extraordinary power of seeing things clearly and of seeing them in their right relations one to another, shown not alone in the artistic side of his nature, but in the scientific, the historical, the social, is a comfort and strength to us that hold in the main the beliefs, made more sacred to us in that they were his, and must give every lover of Shelley pause when he finds himself departing from the master on any fundamental question of economics, a faith, of human life.”

It was not uncommon for atheists, including Shelley, to use the words of religion when attempting to convey passionately held beliefs. And passages and expressions such as these mean that we simply can not underestimate the influence Shelley had on the socialists of this period.

“[What makes Shelley a socialist] is his singular understanding of the facts that today tyranny resolves itself into the tyranny of the possessing class over the producing class.”

In their final section, Marx and Aveling consider Shelley’s use of language, focusing on the words, “anarchy, freedom, custom, crime and property” as well as the concept of the “governing class”. Perceptively and shrewdly, they note that for Shelley the accepted meaning of certain phrases does not align with reality. Thus they touch on what came to be understood as Shelley’s famous capacity for ironic inversion. For example his deployment of the term “anarchy” to describe the then current social system and “rule of law”. For Shelley, they say, anarchy, was “God and King and Law…and let us add…Capitalism.”

On the question of “property”, Marx and Aveling reach their denouement. They begin by quoting a passage from A Philosophical View of Reform that directly anticipates Marx:

Labor, industry, economy, skill, genius, or any similar powers honourably or innocently exerted, are the foundations of one description of property. All true political institutions ought to defend every man in the exercise of his discretion with respect to property so acquired… But there is another species of property which has its foundation in usurpation, or imposture, or violence, without which, by the nature of things, immense aggregations of property could never have been accumulated.

They then paraphrase this in the language of what they call scientific socialism:

“A man has a right to anything his own labour has produced, and that he does not intend to employ for the purpose of injuring his fellows. But no man can himself acquire a considerable aggregation of property except at the expense of his fellows. He must either cheat a certain number out of the value of it, or take it by force.”

With citations from Song to the Men of England, Fragment: To the People of England, Queen Mab and a letter to Hitchener, Marx and Aveling make the case that Shelley understood,

the real economic value of private property in the means of production and distribution, whether it was in machinery, land, funds, what not. He saw that this value lay in the command, absolute, merciless, unjust, over human labour. The socialist believes that these means of production and distribution should be the property of the community. For the man or company that owns them has practically irresponsible control over the class that does not possess them.

And this, they conclude, are the “teachings of Shelley.” And as they are also the teachings of socialism, the two are one and the same thing. Thus Marx and Aveling end with the ringing words, “We claim him as a socialist.”

““We claim him as a socialist.””

According to Marx’s biographer Yvonne Kapp, Shelley’s Socialism was first published by To-day: The Journal of Scientific Socialism in 1888 (Yvonne Kapp, Eleanor Marx, p. 450). It also appeared as a pamphlet in an edition of only twenty-five copies published (presumably by the Shelley Society) for private circulation under the title Shelley and Socialism. In 1947, Leslie Preger (a young Manchester socialist who had fought in the Spanish Civil War) arranged to have it published, with an introduction by the Labour politician Frank Allaun through CWS Printing Work. The Preger edition can be found online through used book services such as AbeBooks. The version published by Preger and that which appeared in To-Day are somewhat different. The version which appears in To-Day appears to have been lightly edited and omits several selections from Shelley’s poetry that appear in the Preger edition. My assumption is that Preger reproduced the pamphlet version released by the Shelley Society. The version I have made available (see link below) is based on Preger and thus is the only complete and “authoritative” version of the speech (as delivered) available on line. You may read it online in it entirety for the first time.

In their speech, Marx and Aveling refer to a second part which they intended to deliver upon some future occasion. Either the second installment has been either lost or perhaps it was never delivered. However, Kapp tantalizingly points out that Engels in fact translated the second part into German for publication in Germany by Die Neue Zeit (Kapp p. 450). No trace of it appears to exist - a loss for us all given the intended subject matter discussed in the speech.

Frank Allaun, author of the preface to the Preger edition, offered this encapsulation of the speech: “A Marxist evaluation of the poetry of Percy Bysshe Shelley.” He concludes his preface with this sage assessment:

“Shelley, who died when his sailing boat sinking a storm in 1822, lived when the Industrial Revolution was only beginning. The owning class had not yet "dug their own graves" by driving the handloom weavers and other domestic workers from their kitchens and plots of land into the "dark satanic mills" alongside thousands of other operatives. Conditions were not ripe for the modern trade union and socialist movement. Had they been so Shelley would have been their man.”

Of the authors, George Bernard Shaw said "he (Aveling) was quite a pleasant fellow who would've gone to the stake for socialism or atheism, but with absolutely no conscience in his private life. He said seduced every woman he met and borrowed from every man. Eleanor committed suicide. Eleanor's tragedy made him infamous in Germany". Shaw added, "While Shelley needs no preface that agreeable rascal Aveling does not deserve one.”

You can read a wonderful encapsulation of Eleanor Marx and her legacy in the Jacobion, here. And you can buy Kapp’s biography of Marx here, though I strongly suggest you instead order it through your local bookseller.

Click the button to go to the speech.

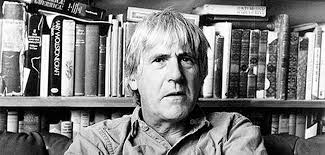

The footnotes in all of the sources are antiquated and refer to out of date editions of Shelley’s poetry and prose - I will in due course provide references to more modern, available texts. Interestingly, there is no mention of the speech in any of the major Shelley biographies. Not even Kenneth Neill Cameron, a Marxist, alludes to it. Nor does Paul Foot reference it in Red Shelley. Thus, it would appear that Aveling’s and Marx’s effort to “claim Shelley as a socialist” had little effect either of the Society or upon public opinion in general. Perhaps this was predictable given the tenor of the times. As Foot observed:

Paul Foot

“In the 1840s as Engels noted, Shelley had been almost exclusively the property of the working class the Chartists had read him for what he was, a tough agitator and revolutionary. The effect of the Shelley-worship of the 1880s and 1890s was too weaken that image; to present for mass consumption a new, wet, angelic Shelley and to promote this new Shelley with all the influence and wealth of respectable academics and publishers.”

Paul Foot offers a disquieting account of the struggle during these years in chapter 7 of Red Shelley. It was a struggle which was largely won by the right and lost by the left. And it would be decades before Kenneth Neil Cameron emerged in the early 1950s to begin the lengthy and arduous process of salvaging Shelley’s left wing credentials. For generations, the Shelley that was embraced by Chartists, by Marx and Engels, would be subsumed by a tidal wave of mawkish Shelleyan “sentimentality’. Gone would be his revolutionary political ardour and in its place appeared a carefully curated selection of poetry designed to showcase only Shelley’s lyrical capabilities - his love poems.

Interestingly, to call Shelley a “love poet” can be intensely misleading. Many modern readers encountering the term “love poet” will think immediately of romantic or sexual love - and there is no doubt that Shelley wrote many poem that were almost purely romantic. However, when Shelley speaks of love, you have to look carefully at what he is saying, and what he is almost always talking about is empathy, that is the ability to imagine and understand the thoughts, perspective, and emotions of another person; to put yourself in their shoes, as it were. Shelley should therefore be thought of as the “poet of empathy” and of revolutionary love.

“Shelley should be thought of as the poet of empathy and, if anything, of revolutionary love.”

Isabel Quigley’s selection of Shelley’s Poetry: “No poet better repays cutting.”

For example, in the first part of the 20th century, Gresham Press offered a highly popular selection of poems by English poets. In the introduction to the Shelley volume, the poet and editor Alice Meynell (also a vice president of the Women Writers' Suffrage League) cheerfully announced that “ This volume leaves out all Shelley’s contentious poems.”

As recently as 1973, Kathleen Raine, in Penguin’s Poet to Poet series, omitted important poems such as Laon and Cythna - as well as most of the rest of his overtly political output. And she did so with considerable gusto, stating explicitly that she did so “without regret”. In a widely available edition of his poetry, the editor, Isabel Quigly, cheerfully notes, “No poet better repays cutting; no great poet was ever less worth reading in his entirety".

Fortunately Shelleyan scholarship has now long since passed through this dark period in his reception. The annus mirabilis in this regard was 1980, the year in which PMS Dawson published his book, Unacknowledged Legislator: Shelley and Politics, Paul Foot published Red Shelley, and Michael Scrivener published Radical Shelley: The Philosophical Anarchism and Utopian Thought of Percy Bysshe Shelley. All three owe an enormous debt to perhaps the greatest of Shelley’s politically minded biographers, the Marxist Kenneth Neill Cameron whose magisterial volume The Young Shelley: Genesis of a Radical appeared in 1958. This is a book of which one can truly be in awe.

Can Poetry Change the World?

When Shelley said poets were the "unacknowledged legislators of the world", he used the term "legislator" in a special sense. Not as someone who "makes laws" but as someone who is a "representative" of the people. In this sense poets, or creators more generally, must be thought of as the voice of the people; as a critical foundation of our society and of our democracy. They offer insights into our world and provide potential solutions - they underpin our future. An attack on creators is therefore an attack on the very essence of humanity.

First published in June of 2017, Graham’s article (see below) reflected on the UK Labour Party’s use of a quote from Shelley’s Mask of Anarchy: “For The Many. Not For The Few”. The line was in fact the Party’s campaign slogan. Today, this article has sudden new relevance due to developments in Europe.

With the recent election of Boris Johnson as Prime Minister in the United Kingdom and the looming risk that the governing Conservatives under his tutelage may be toppled by the Labour Party opposition at any moment, Jeremy Corbyn has been catapulted into the spotlight. If politics is fundamentally a contest of different visions of the future, then the visions of each of the respective party leaders could not be more antithetical. At heart of the Brexit debate that has tattered the nation’s fabric is not simply an issue of securing economic prosperity, but rather an issue of who belongs and who may prosper in the national fold. Consistent with the political trend abroad, the leaders’ have appealed to nationalist sentiments in order to shore up support, but the meaning behind the oft bantered catch-phrase “the people” could not be more different.

While the Brexit debate is voiced as an economic issue that if successful would ultimately recuperate the nation’s prosperity, lingering behind the economic claims is an implicit attempt to reshape the nation’s social pattern by redefining its foreign ties. The irony, of course, is that the United Kingdom’s wealth is precisely the result of its long imperial history abroad. Just as the onset of industrialism and the imperial phase in which it was a part led to the mass dispossession of the lower classes as the feudal economy was reformed, dispossession continues in a more insidious form today as wealth becomes ever more concentrated in the hands of the few. Even if Brexit is an attempt to restore the prosperity of the masses as the Conservatives claim it will do, that claim is revealed as specious considering the centrality of transnational capital to its economic policies. Although both parties appeal to class-based claims about how to rejuvenate the prosperity of the commonweal, the Conservatives’ attempt to redefine Britain’s relationship with continental Europe specifically gestures toward the real essence of its aim: to define who belongs in the commonweal, for which the policies of the European Union are categorically problematic. The attempt to break ties with the EU speaks more to Brexit supporters’ longing to undermine the nation’s pluralism than the goal of recuperating the nation’s wealth.

Shelley’s early draft of “Ode to the West Wind,” 1819, Bodleian Library

Writing at the height of Britain’s colonial reign, Shelley, unlike some of his contemporaries such as John Clare or William Wordsworth, actually saw globalization in a positive light. While The Mask of Anarchy is often invoked as a key poem evincing Shelley’s social philosophy, his later poem “Ode to the West Wind,” written one year after Mask of Anarchy in 1820, makes interesting—and certainly timely—linkages between racial politics, globalization, and poetic creation. At first glace the autumn leaves—“Yellow, black, and pale, and hectic red”—appear to be stock botanical metaphors, but closer inspection uncovers that they represent various races who collectively comprise the “pestilence-stricken multitudes.” Pestilence-stricken not just because the west wind has desiccated them, but because the West is where so much of the colonial activity is occurring at this time, namely the transatlantic slave trade and plantation slavery in the Americas. Of course, the United Kingdom is also geographically West, perhaps intimating how the colonial enterprise has affected nations in the East. While Shelley identifies how globalization can have negative social ramifications, he nevertheless one of its ardent proponents. Just as the seeds that lay dormant require the spring rains that are incited by the cyclical ebb and flow of winds around the earth, the poet summons those same winds as a source of poetic inspiration. Poetic inspiration is thereby syncretic, fostered by global myths that capture—and envision—a universal humanity. In a moment when that universal humanity is under siege by cordoning off borders and shoring up nationalist sentiment, we need to look at its social and poetical implications alike.’

With that said, here is what Graham had to say on 2017.

James Regan, University of Toronto.

Fiona Sampson has written an absolutely brilliant article which I urge you to spend some time with and share widely. She opens by referencing Shelley's Defense of Poetry and his famous claim that "poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world." She also cites The Mask of Anarchy. You can find it here: Jeremy Corbyn is Right: Poetry Can Change the World.

In an other excellent article (From Glastonbury to the Arab Spring, Poetry can Mobilize Resistance) in the same online news source, Atef Alshaer, Lecturer in Arabic Studies at the University of Westminster, looks at other instances of poetry's power in the political context. "Poetry," he notes, "has remained a potent force for mobilization and solidarity." He traces the influence of Shelley to the words of the Tunisian poet, Abu al-Qassim al-Shabbi (1909-1934). He also observes that Shelley's words were "echoed across the Middle East within the context of what has been called the 'Arab Spring'."

It is important, however, to understand what Shelley meant when he said poets were the "unacknowledged legislators of the world." I believe it was PMS Dawson who pointed out that Shelley used the term "legislator" in a special sense. Not as someone who "makes laws" but as someone who is a "representative" of the people. In this sense poets, or creators more generally, must be thought of as the voice of the people; as a critical foundation of our society and of our democracy. They offer insights into our world and provide potential solutions - they underpin our future. An attack on creators is therefore an attack on the very essence of humanity.

Exposure to cultural works also engenders and inculcates empathy. Shelley thought poetry was the greatest expression of the imagination. This was important because as a skeptic he believed that the human imagination was the principle organ we use to understand the world. A defective imagination can lead to dangerous errors. You might, as did Coleridge, look at the sublimity of Mont Blanc and be misled into thinking it was the work of an external deity. And for Shelley, that is the beginning of a great error that would lead to the abdication of personal responsibility and accountability. He would prefer to look upon the sublimity of Mont Blanc and see a "vacancy". This doesn't mean he saw nothing. This simply means that there is nothing there except as we perceive it. In other words we make our own world. If we abdicate responsibility for what happens in the world, we get what we deserve.

I was recently at a ceremony hosted by the Government of Ontario that was intended to honour its most outstanding citizens. One of them was a "reverend" who was foolishly permitted to offer the "invocation." In the course of this she asked us to thank god for the fact that to the extent we had special gifts - we owed it to god. In other words, what "gifts" we have, we have because of god - they were given to us - not earned or developed. This pernicious idea is exactly the sort of nonsense Shelley was rebelling against. I almost turned my back on the podium.

It is therefore a most welcome development that as a result of the recent British election, poetry in general and Shelley in particular have been brought to center stage. Thank you Mr. Corbyn. And let us not underestimate the importance of Shelley to what happened. A general election in one the world's largest democracies was just fought out on ground staked out by Shelley 200 years ago. Labour's motto, "For The Many. Not For The Few", was directly taken from Shelley's "Mask of Anarchy. Read more about the history of this great poem here.

The motto brilliantly captured (or did it create?) an evolving zeitgeist. People are fed up with the current status quo: wealth is concentrating in fewer hands that at almost any point in human history. Shelley knew that. And he found an ingenious manner of expressing that thought. Someone in the Labour Party winged on to this and the rest is history. I firmly believe that motto was responsible for capturing the imagination of youth and bringing them to the polls. Was Shelley worth 30 seats? He may well have been.

But back to "unacknowledged legislators." I think we are better off to think of Shelley's statement as pertaining to all of the creative arts and not just poetry. Shelley was answering a particular charge at a particular juncture in history - his friend Peacock's suggestion that poetry was pointless. Today the liberal arts and the humanities are under a similar attack by the parasitic, cultural vandals of Silicon Valley. Right across the United States, Republican governors are rolling back support for state universities that offer liberal arts education. The mantra of our day is "Science. Technology. Engineering. Mathematics." Or STEM for short. This is not just a US phenomenon. I see it happening in Canada as well. There is a burgeoning sense that a liberal arts education is worthless.

Culture is worth fighting for - for the very reasons Shelley set out. What Shelley called a "cultivated imagination" can see the world differently - through a lens of love and empathy. Our "gifts" are not given to us by god - we earn them. They belong to us. We should be proud of them. The idea that we owe all of this to an external deity is vastly dis-empowering. And it suits the ruling order.

A corollary of this, also encapsulated in Shelley's philosophy, is the importance of skepticism. A skeptical, critical mind always attacks the truth claims of authority. And authority tends to rely upon truth claims that are disconnected from reality: America is great because god made it great. Thus Shelley was fond of saying, "religion is the hand maiden of tyranny."

It should therefore not surprise anyone that many authoritarian governments seek to reinforce the power of society's religious superstructure. This is exactly what Trump is doing by blurring the line between church and state. Religious beliefs dis-empower the people - they are taught to trust authority.

A recent development has been the re-emergence of stoicism - it is the pet ancient philosophy of the "tech bros", the overlords of Silicon Valley. And it is a very convenient one indeed - because it is in effect a slave's philosophy that teaches us to accept those things over which we have no control. And if the companion philosophy is that technological developments are inevitable, then stoicism suits the governing techno-utopian order perfectly. You can read what Cambridge philosopher Sandy Grant has to say about this here.

If there is an ancient philosophy that we need right now, it is skepticism - a philosophy which teaches to to question all authority. Coupled with an empathetic "cultivated imagination", developed through exposure to culture, you have a lethal one-two punch that threatens the foundation of all authoritarians.

We can thank Shelley for piecing this all together. Poets and creators may have been the "unacknowledged legislators of the world" in Shelley's time. But perhaps no longer. Now, let's haul ass to the barricades.

Eugene Delacroix, Liberty Leading the People, oil on canvas, 1830

James Regan is an English Literature scholar at the University of Toronto and also works with me as a research and editorial assistant.

Happy Zodiacal Valentine's Day From Percy Bysshe Shelley!!

WHO ARE YOU IN SHELLEY'S ROMANTIC ZODIAC?!?!

Do you want to know which love poem rules your sign? Which poem speaks to the heart of your loved one? Well look no further. We got ya covered. Happy Valentine’s Day Shelley Nation! Follow the link and dig in.

At last! Someone has undertaken a close reading of Shelley’s most romantic poems in order to match them with the 12 astrological signs! Who did this amazing thing? The Real Percy Bysshe Shelley did - that’s who.

Happy Valentine’s Day From Percy Bysshe Shelley!!

Here at The Real Percy Bysshe Shelley I spend a lot of time focusing on Shelley’s political and philosophical writings. Around here I can sometimes forget that PB was one of the greatest of all love poets. And so this being Valentine’s Day it seems only right and proper that I should unleash the majesty of his (small “r”) romantic poems. To add some fun to the proceedings I decided to introduce an astrological element. A famous skeptic and a man who was disdainful of superstition, Shelley would probably be appalled by what I am up to here. But then again, contrary to the common misconception, Shelley had a great sense of humour - so maybe he would love this. Let’s hope so. But in any event, it is Valentine’s Day and the spirits of Eros and Cupid are in charge, so I am going to jump in with both feet.

And here it is! Hilda Pagan’s horoscope for me.

I wanted to try to match some of his most beautiful poems with the twelve astrological signs. Do you want to know which love poem rules your sign? Which poem speaks to the heart of your loved one? Well look no further. I order to make this all happen, I needed to speak to astrological experts. Knowing none, I was left in a quandary. It then occurred to me that my great Aunts Hilda and Isabel Pagan (yes, that is their name) were both astrologers of the first order. In fact they cast a horoscope for me (see image) at the hour of my birth - a horoscope so uncannily accurate that my mother kept it hidden from me until I was in my twenties!. One problem - they are both dead.

Where there is a will there is a way. Thanks to the magic of the ouija board, I was able to communicate with them. It took a little time (letter by letter!) but i am now pleased to present a selection of Shelley’s love poetry matched to each of the 12 astrological signs. No one in the history of the world has ever performed this astounding feat of astro-poetical genius. Let’s dig in.

Aries: March 21 – April 19

Aries. You are from the first House, the House of Self. This can make it challenging to choose a partner but where love is concerned, under the fire sign and the ruling celestial body of Mars, choosing yourself might be the right idea!

The Question

I dreamed that, as I wandered by the way,

Bare Winter suddenly was changed to Spring,

And gentle odours led my steps astray,

Mixed with a sound of waters murmuring

Along a shelving bank of turf, which lay

Under a copse, and hardly dared to fling

Its green arms round the bosom of the stream,

But kissed it and then fled, as thou mightest in dream.

There grew pied wind-flowers and violets,

Daisies, those pearled Arcturi of the earth,

The constellated flower that never sets;

Faint oxlips; tender bluebells, at whose birth

The sod scarce heaved; and that tall flower that wets —

Like a child, half in tenderness and mirth —

Its mother's face with Heaven's collected tears,

When the low wind, its playmate's voice, it hears.

And in the warm hedge grew lush eglantine,

Green cowbind and the moonlight-coloured may,

And cherry-blossoms, and white cups, whose wine

Was the bright dew, yet drained not by the day;

And wild roses, and ivy serpentine,

With its dark buds and leaves, wandering astray;

And flowers azure, black, and streaked with gold,

Fairer than any wakened eyes behold.

And nearer to the river's trembling edge

There grew broad flag-flowers, purple pranked with white,

And starry river buds among the sedge,

And floating water-lilies, broad and bright,

Which lit the oak that overhung the hedge

With moonlight beams of their own watery light;

And bulrushes, and reeds of such deep green

As soothed the dazzled eye with sober sheen.

Methought that of these visionary flowers

I made a nosegay, bound in such a way

That the same hues, which in their natural bowers

Were mingled or opposed, the like array

Kept these imprisoned children of the Hours

Within my hand,— and then, elate and gay,

I hastened to the spot whence I had come,

That I might there present it! — Oh! to whom?

— Written in 1820, this poem was published by Leigh Hunt in The Literary Pocket-Book in 1822.

Taurus: April 20 – May 20

Ruled by Venus but under a terrestrial sign, your earthly concern on Valentine’s Day is sharing a night with your honey. Shelley has you covered. Curl up with this beauty...and indulge in breakfast in bed in the morning no matter who cooks!

Goodnight

Good-night? ah! no; the hour is ill

Which severs those it should unite;

Let us remain together still,

Then it will be good night.

How can I call the lone night good,

Though thy sweet wishes wing its flight?

Be it not said, thought, understood —

Then it will be — good night.

To hearts which near each other move

From evening close to morning light,

The night is good; because, my love,

They never say good-night.

— Written in 1820, this poem was published by Leigh Hunt in The Literary Pocket-Book in 1822.

Gemini: May 21 – June 20

You are a thinker, Gemini. Your twin soul weighs past and future equally. Shelley’s thoughtful poem The Recollection captures your understanding of the balance of past and future. Is there someone you should reach out to and send a little note that you’re thinking of them?

To Jane: The Recollection

Now the last day of many days,

All beautiful and bright as thou,

The loveliest and the last, is dead,

Rise, Memory, and write its praise!

Up, — to thy wonted work! come, trace

The epitaph of glory fled, —

For now the Earth has changed its face,

A frown is on the Heaven’s brow.

We wandered to the Pine Forest

That skirts the Ocean’s foam,

The lightest wind was in its nest,

The tempest in its home.

The whispering waves were half asleep,

The clouds were gone to play,

And on the bosom of the deep

The smile of Heaven lay;

It seemed as if the hour were one

Sent from beyond the skies,

Which scattered from above the sun

A light of Paradise.

We paused amid the pines that stood

The giants of the waste,

Tortured by storms to shapes as rude

As serpents interlaced;

And soothed by every azure breath,

That under Heaven is blown,

To harmonies and hues beneath,

As tender as its own;

Now all the tree-tops lay asleep,

Like green waves on the sea,

As still as in the silent deep

The ocean woods may be.

How calm it was! — the silence there

By such a chain was bound

That even the busy woodpecker

Made stiller by her sound

The inviolable quietness;

The breath of peace we drew

With its soft motion made not less

The calm that round us grew.

There seemed from the remotest seat

Of the white mountain waste,

To the soft flower beneath our feet,

A magic circle traced, —

A spirit interfused around,

A thrilling, silent life,

To momentary peace it bound

Our mortal nature’s strife;

And still I felt the centre of

The magic circle there

Was one fair form that filled with love

The lifeless atmosphere.

We paused beside the pools that lie

Under the forest bough,—

Each seemed as ’twere a little sky

Gulfed in a world below;

A firmament of purple light

Which in the dark earth lay,

More boundless than the depth of night,

And purer than the day —

In which the lovely forests grew,

As in the upper air,

More perfect both in shape and hue

Than any spreading there.

There lay the glade and neighbouring lawn,

And through the dark green wood

The white sun twinkling like the dawn

Out of a speckled cloud.

Sweet views which in our world above

Can never well be seen,

Were imaged by the water’s love

Of that fair forest green.

And all was interfused beneath

With an Elysian glow,

An atmosphere without a breath,

A softer day below.

Like one beloved the scene had lent

To the dark water’s breast,

Its every leaf and lineament

With more than truth expressed;

Until an envious wind crept by,

Like an unwelcome thought,

Which from the mind’s too faithful eye

Blots one dear image out.

Though thou art ever fair and kind,

The forests ever green,

Less oft is peace in Shelley’s mind,

Than calm in waters, seen.

— Written in 1821 and published in this form by Mary Shelley in The Poetical Works of Percy Bysshe Shelley, 1839, 2nd edition.

Cancer: June 21 – July 22

Guided by the moon and water you respond to the romance of the night and your environment. Delight in the mood and the atmosphere on Valentine’s Day with this literary treat. Good lighting, relaxing music and a great glass of wine can do wonders.

To Jane: “The Keen Stars Were Twinkling”

The keen stars were twinkling,

And the fair moon was rising among them,

Dear Jane!

The guitar was tinkling,

But the notes were not sweet till you sung them

Again.

As the moon's soft splendour

O'er the faint cold starlight of Heaven

Is thrown,

So your voice most tender

To the strings without soul had then given

Its own.

The stars will awaken,

Though the moon sleep a full hour later,

To-night;

No leaf will be shaken

Whilst the dews of your melody scatter

Delight.

Though the sound overpowers,

Sing again, with your dear voice revealing

A tone

Of some world far from ours,

Where music and moonlight and feeling

Are one.

Written in 1822, the poem was published in part under the title An Ariette for Music. To a Lady Singing to her Accompaniment on the Guitar by Shelley’s cousin Thomas Medwin in 1832. Mary later published in full under the title To — in The Poetical Works of Percy Bysshe Shelley , 2nd Edition. We now know the poem was written to Jane Williams.

Leo: July 23 – August 22

Sun driven Leo! Headstrong lion from the House of Pleasure, whisk your Valentine away for an unforgettable trip….even if you are your own Valentine. Life’s joys are many. Pamper yourself and try to set a record for favourite things done today. This is Shelley’s sign - he was born 4 August 1792!!

To Jane: The Invitation

Best and brightest, come away!

Fairer far than this fair Day,

Which, like thee to those in sorrow,

Comes to bid a sweet good-morrow

To the rough Year just awake

In its cradle on the brake.

The brightest hour of unborn Spring,

Through the winter wandering,

Found, it seems, the halcyon Morn

To hoar February born.

Bending from Heaven, in azure mirth,

It kiss'd the forehead of the Earth,

And smiled upon the silent sea,

And bade the frozen streams be free,

And waked to music all their fountains,

And breathed upon the frozen mountains,

And like a prophetess of May

Strewed flowers upon the barren way,

Making the wintry world appear

Like one on whom thou smilest, dear.

Away away from men and towns,

To the wild woods and the downs —

To the silent wilderness

Where the soul need not repress

Its music lest it should not find

An echo in another's mind ,

While the touch of Nature's art

Harmonizes heart to heart.

I leave this notice on my door

For each accustomed visitor: —

“I am gone into the field

To take what this sweet hour yields; —

Reflection, you may come tom-morrow,

Sit by the fireside with Sorrow, —

You with the unpaid bill, Despair, —

You tireseome verse-reciter, Care, —

I will pay you in the grave, —

Death will listen to your stave.

Expectation too, be off!

To-day is for itself enough;

Hope, in pity mock not Woe

With smiles, nor follow where I go;

Long having lived on thy food,

At length I find one moment’s good

After long pain — with all your love,

This you never told me of.”

Radiant Sister of the Day

Awake! arise! and come away!

To the wild woods and the plains,

To the pools where winter rains

Image all their roof of leaves,

Where the pine its garland weaves

Of sapless green and ivy dun

Round stems that never kiss the sun;

Where the lawns and pastures be

And the sandhills of the sea; —

Where the melting hoar-frost wets

The daisy-star that never sets,

And wind-flowers and violets,

Which yet join not scent to hue,

Crown the pale year weak and new;

When the night is left behind

In the deep east dim and blind,

And the blue noon is over us ,

And the multitudinous

Billows murmur at our feet,

Where the earth and ocean meet

And all things seem only one

In the universal Sun.

— Written in 1821 and published in this form by Mary Shelley in The Poetical Works of Percy Bysshe Shelley, 1839, 2nd edition.

Virgo: August 23 – September 22

Virgos analyze. Analyze this gem inspired by Shakespeare. Are you in a relationship? Could there be someone nearby who also loves you? You are valued and cherished, thoughtful Virgo! Word to the wise - if someone gives you a guitar, they probably have a crush on you! This is Mary’s sign - she was born 30 August 1797!!

With a Guitar, To Jane - an Excerpt

Ariel to Miranda: — Take

This slave of Music, for the sake

Of him who is the slave of thee,

And teach it all the harmony

In which thou canst, and only thou,

Make the delighted spirit glow,

Till joy denies itself again,

And, too intense, is turn'd to pain;

For by permission and command

Of thine own Prince Ferdinand,

Poor Ariel sends this silent token

Of more than ever can be spoken;

Your guardian spirit Ariel, who,

From life to life, must still pursue

Your happiness; — for thus alone

Can Ariel ever find his own.

From Prospero's enchanted cell,

As the mighty verses tell,

To the throne of Naples, he

Lit you o'er the trackless sea,

Flitting on, your prow before,

Like a living meteor.

When you die, the silent Moon

In her interlunar swoon,

Is not sadder in her cell

Than deserted Ariel.

When you live again on earth,

Like an unseen star of birth,

Ariel guides you o'er the sea

Of life from your nativity.

Many changes have been run

Since Ferdinand and you begun

Your course of love, and Ariel still

Has track'd your steps, and served your will;

Now, in humbler, happier lot,

This is all remembered not;

And now alas! the poor sprite is

Imprisoned for some fault of his,

In a body like a grave; —

From you he only dares to crave,

For his service and his sorrow

A smile to-day, a song to-morrow.

The artist who this idol wrought,

To echo all harmonious thought,

Felled a tree while on the steep

The woods were in their winter sleep,

Rocked in that repose divine

On the wind-swept Apennine;

And dreaming some of Autumn past,

And some of Spring approaching fast,

And some of April buds and showers,

And some of songs in July bowers,

And all of love; and so this tree, —

Oh that such our death may be! —

Died in sleep and felt no pain ,

To live in happier form again;

From which beneath Heaven's fairest star,

The artist wrought this loved Guitar;

And taught it justly to reply,

To all who question skilfully,

In language gentle as thine own;

Whispering in enamour'd tone

Sweet oracles of woods and dells,

And summer winds in sylvan cells;

For it had learnt all harmonies

Of the plains and of the skies ,

Of the forests and the mountains

And the many-voicèd fountains;

The clearest echoes of the hills,

The softest notes of falling rills,

The melodies of birds and bees,

The murmuring of summer seas,

And pattering rain, and breathing dew,

And airs of evening; and it knew

That seldom-heard mysterious sound,

Which driven on its diurnal round ,

As it floats through boundless day,

Our world enkindles on its way, —

All this it knows but will not tell

To those who cannot question well

The spirit that inhabits it;

It talks according to the wit

Of its companions; and no more

Is heard than has been felt before,

By those who tempt it to betray

These secrets of an elder day:

But sweetly as its answers will

Flatter hands of perfect skill,

It keeps its highest, holiest tone

For one belovèd Jane alone.

— Written in 1822, this poem was published by Medwin in The Athenæum on 30 October 1832.

Libra: September 23 – October 22

Symmetry and balance are in the air for you, Libra. One of Shelley’s greatest poems gives you all of that and more. You juggle thinking and feeling all day long. Perhaps succumb to feeling every now and then. Especially for a romantic special occasion such as this.

Love’s Philosophy

The fountains mingle with the river

And the rivers with the Ocean,

The winds of Heaven mix for ever

With a sweet emotion;

Nothing in the world is single;

All things by a law divine

In one spirit meet and mingle.

Why not I with thine? —

See the mountains kiss high Heaven

And the waves clasp one another;

No sister-flower would be forgiven

If it disdained its brother;

And the sunlight clasps the earth

And the moonbeams kiss the sea:

What is all this sweet work worth

If thou kiss not me?

— Written in 1819, the poem was first published by Leigh Hunt inThe Indicator on 22 December 1819.

Scorpio: October 23 – November 21

Sensuous and dreamlike, yet physical and organic, your keyword is desire, Scorpio. Desire with a capital D. Drama also starts with a D... You know your power but your love might not understand the full scope of it. Focus your energy on treating your Valentine and try not to slip into the second D word.

The Indian Serenade

I arise from dreams of thee

In the first sweet sleep of night.

When the winds are breathing low,

And the stars are shining bright:

I arise from dreams of thee,

And a spirit in my feet

Has led me — who knows how?

To thy chamber-window, Sweet!

The wandering airs they faint

On the dark, the silent stream —

The Champak odours fail

Like sweet thoughts in a dream;

The nightingale's complaint,

It dies upon her heart; —

As I must die on thine,

Oh, belovèd as thou art!

O, lift me from the grass!

I die, I faint, I fall!

Let thy love in kisses rain

On my lips and eyelids pale.

My cheek is cold, and white, alas!

My heart beats loud and fast; —

Oh! press it close to thine own again,

Where it will break at last.

— Written in 1819 this poem was published with the title Song written for an Indian Air, in The Liberal, volume 2, 1822.

Sagittarius: November 22 – December 21

You are a traveler, Sagittarius. You understand the need for new surroundings and what fleeting experiences do to impact your ideas of time and memory. Love is like that as well and sometimes sharp inclines of joy and declines of sorrow only reinforce the immediacy of life and the beauty of each moment. Cherish this moment.

Mutability

We are as clouds that veil the midnight moon;

How restlessly they speed, and gleam, and quiver,

Streaking the darkness radiantly! — yet soon

Night closes round, and they are lost for ever:

Or like forgotten lyres, whose dissonant strings

Give various response to each varying blast,

To whose frail frame no second motion brings

One mood or modulation like the last.

We rest. — A dream has power to poison sleep;

We rise. — One wandering thought pollutes the day;

We feel, conceive or reason, laugh or weep;

Embrace fond woe, or cast our cares away:

It is the same! — For, be it joy or sorrow,

The path of its departure still is free:

Man's yesterday may ne'er be like his morrow;

Nought may endure but Mutabililty.

— Written in 1816, the poem was published with Alastor in the same year.

Capricorn: December 22 – January 19

You have sense, Capricorn. You have roots in wisdom and earth. You certainly have the wherewithal and savvy to convince a crush to give you a chance or the judgement to choose a suitable suitor/suitress. Maybe this could be an opportunity to use your wisdom and savvy for mutual gratification!

Epipsychidion — an excerpt

Thy wisdom speaks in me, and bids me dare

Beacon the rocks on which high hearts are wrecked.

I never was attached to that great sect,

Whose doctrine is, that each one should select

Out of the crowd a mistress or a friend,

And all the rest, though fair and wise, commend

To cold oblivion, though it is in the code

Of modern morals, and the beaten road

Which those poor slaves with weary footsteps tread,

Who travel to their home among the dead

By the broad highway of the world, and so

With one chained friend, perhaps a jealous foe,

The dreariest and the longest journey go.

True Love in this differs from gold and clay,

That to divide is not to take away.

Love is like understanding, that grows bright,

Gazing on many truths; ’tis like thy light,

Imagination! which from earth and sky,

And from the depths of human phantasy,

As from a thousand prisms and mirrors, fills

The Universe with glorious beams, and kills

Error, the worm, with many a sun-like arrow

Of its reverberated lightning. Narrow

The heart that loves, the brain that contemplates,

The life that wears, the spirit that creates

One object, and one form, and builds thereby

A sepulchre for its eternity.

— This excerpt (lines 147 - 173) is from Epipsychidion which was was written in 1821 and published (without Shelley’s name) in the summer of 1822.

Aquarius: January 20 – February 18

Cup bearer! Aquarius, you understand water, air and friendship. You are willing to ride along on the tide of another’s passion because you feel you just know. This is a beautiful trait. If you are with someone right now, give them the tiller on your love boat. If you are not, perhaps now is the time to try something you are unsure of because it could be something magical. Who knows?

My Soul is an Enchanted Boat - an excerpt from Prometheus Unbound

My soul is an enchanted boat,

Which, like a sleeping swan, doth float

Upon the silver waves of thy sweet singing;

And thine doth like an angel sit

Beside a helm conducting it,

Whilst all the winds with melody are ringing.

It seems to float ever, for ever,

Upon that many-winding river,

Between mountains, woods, abysses,

A paradise of wildernesses!

Till, like one in slumber bound,

Borne to the ocean, I float down, around,

Into a sea profound, of ever-spreading sound:

Meanwhile thy spirit lifts its pinions

In music's most serene dominions;

Catching the winds that fan that happy heaven.

And we sail on, away, afar,