Atheist, Lover of Humanity, Democrat

PERCY BYSSHE SHELLEY

Shelleyana!! My Father's Shelley, Part Two

Shelley had an enormous impact on me and my dad's life - though we had radically different ideas about exactly who Shelley was (which was the subject of part one of this essay). I want to explore this theme by digging into a photographic album I discovered among my father's effects after he died. It is a slim volume entitled "Shelleyana". I think we will find much to reflect upon, and Shelley may perhaps seem less remote and more immediate.

"Williams is captain, and we drive along this delightful bay in the evening wind, under the summer moon, until earth appears another world. Jane brings her guitar, and if the past and the future could be obliterated, the present would content me so well that I could say with Faust to the passing moment, "Remain thou, thou art so beautiful'."

Letter to John Gisborne, 18 June 1822. The Letters of Shelley, II 435-6

We all know what happened 16 days later; the past, the present and the future were indeed obliterated.

It is the anniversary of Shelley's death today [this article was written on July 8th 2017], and I thought the best way to observe this sad occasion was to turn again to the enormous impact Shelley on me and my dad's life - though we had radically different ideas about exactly who Shelley was. The "different" Shelleys were the subject of my essay, My Father's Shelley: A Tale of Two Shelleys." I want to further explore this theme by digging into a photographic album I discovered among my father's effects after he died. It is a slim volume entitled "Shelleyana". I think we will find much to reflect upon, and Shelley may perhaps seem less remote and more immediate.

My father's interest in Shelley must have started very early for reasons that will emerge quickly. And that fact that it did so inevitably leads my to conclude that his mother, Edith Wills, must have had something to do with it. She had an absolutely incalculable effect on his life. One of the reasons I know this is that shortly before his death I came into possession of hundreds of letters that he had written to her. She appears to have kept almost all of them. There is a generous sprinkling of those she wrote to him, but he does not appear to have been as concerned for posterity as she was.

My father was born in 1916 in Montreal, Canada. Very early in life he exhibited an aptitude for, and an interest in, the arts. This came from his mother, and not his father. He assiduously studied music and was good enough that he was in a position at one point to chose a career as a professional pianist. But he abandoned this for the stage. In his late teens he was active in the Montreal theatrical community. Then he did something truly extraordinary. In 1936, at age 18 he boarded a ocean liner and sailed for England to pursue an acting career.

While he did not appear to have set the acting word on fire, he did seem to progress his career until the Second World War ruined his dreams as it did those of almost everyone else on the planet.

The cover of my father's Shelley "scrap book".

While in England he also took the time to pursue a passion of his: Percy Bysshe Shelley. I know this because I have an unusual little scrap book which I found on his shelf with the rest of his Shelley materials. It is a bit shabby now, but he appears to have spent considerable effort to put it together - beginning in 1937.

"Shelleyana"

Now the term "Shelleyana" is an interesting term in and of itself, and I have been unable to find any "official" definition for it. It is used to refer to collections of materials that pertain to Shelley and his circle. It is clearly a coined term and I can think of no other example of it. There is an affectionate overtone; it strikes one as diminutive. It is even a little cloying. All of which is entirely in keeping with the manner in which Shelley was viewed by a large segment of the literate intelligentsia in the 19th century. I wrote about this in my article, "Shelley in the 21st Century."

Many people who held Shelley in high esteem had collections of "Shelleyana". These might be relics, or they might be first editions, or they might be rare or unusual books about him or those he was close to. For example, here is an article from the New York Times in 1922 extolling a particular collection of Shelleyana which was available to the public on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of his death.

My father always referred to his collection of books on Shelley as his "Shelleyana". And as suits the reverential, almost hagiographic overtone, which the term connotes, his scrap book begins with not one, but THREE portraits of the poet - each accorded its own page.

Amelia Curran's 1819 portrait of Shelley which hangs in the National Portrait Gallery

This is the most famous, even iconic, of the portraits. Shelley sat for Curran in Rome on May 7 and 8 in 1819. Curran was known to Shelley and Mary and they had last encountered her in Godwin's home in 1818. Crucially, this painting was NOT finished in his life time, and must be considered to be an extremely unreliable likeness. Shelley's biographer, James Bieri notes, "It has become the misleading image by which so many have misperceived Shelley." We know that neither Mary nor Shelley liked it - nor did his friends. The history of this painting and its effect on the way in which Shelley came to be regarded can not be underestimated, but this is not the time and place for such a discussion. Suffice to say that it played directly into the hands of those Victorians who preferred to imagine Shelley as a child-like, almost androgynous being - this is the "castrated" Shelley (in Engles' famous phrase). The man in this painting is NOT my Shelley - but it was most decidedly my father's Shelley.

Here is the second:

A crayon portrait based on the painting by George Clint

Well, what can you say? Here Shelley has lost almost all of his masculine characteristics and the ethereal being the Victorians (and my father) so came to adore is born. We are getting very close Mathew Arnold's vision of Shelley as "a beautiful and ineffectual angel, beating in the void his luminous wings in vain". Clint's portrait was painted in 1829 years after his death, and is known to be a composite of Curran's painting and a sketch by Shelley's friend, Edward Williams.

Sketch by Edward Ellerker Williams, Pisa, 27 November 1821

Curran's painting was repainted several times and each time, Shelley become less recognizable, more child-like, more androgynous, more ethereal. I believe these images of Shelley played a central role in the re-invention and distortion of his reputation. For example, here is Francis Thompson (one of his Victorian idolators) writing in 1889:

“Enchanted child, born into a world unchildlike; spoiled darling of Nature, playmate of her elemental daughters; "pard-like spirit, beautiful and swift," laired amidst the burning fastnesses of his own fervid mind; bold foot along the verges of precipitous dream; light leaper from crag to crag of inaccessible fancies; towering Genius, whose soul rose like a ladder between heaven and earth with the angels of song ascending and descending it;--he is shrunken into the little vessel of death, and sealed with the unshatterable seal of doom, and cast down deep below the rolling tides of Time.” - Francis Thompson, "Shelley", 1889

The story of the incalculable damage that these stylized images wrought, divorced as they were from reality, has yet to be properly told. But I think it is fair to say that had no portraits of Shelley ever existed, we might see him in a very different light today. I think that portraits like these fed a particular vision of Shelley that my father fed off. Looking into the eyes of these three Shelleys, it is difficult to see the revolutionary, the philosophical anarchist, the atheist that he was.

Postcard purchased at the Bodleian by my father, July 1937

On the next page we find, not unsurprisingly, a postcard my dad purchased in July, 1937 in Oxford at the Bodleian. It displays certain Shelley "relics". These are: (1) the copy of Sophocles allegedly taken from Shelley's hand after his body washed ashore; (2) locks of Shelley's and Mary's hair; (3) a portrait of him as a boy; (4) his baby's rattle; and (5) his pocket watch and seals.

The idea that Shelley was found with that book in his hand is a story we owe to one of the most notorious liars in history, Edward Trelawny who for his entire life trafficked in stories derived from his association with Shelley and Byron - two men, both dead, who could not contradict his lies. There are certain element of his biography of Shelley which we can take at face value, but they are few and far between. But stories like that, when the become "relics" and part of "Shelleyana" feed myths. My dad was always fond of Trelawny - and Trelawny did my father the ultimate disfavour of serving up a vision of Shelley that was almost completely divorced from reality.

Onslow Ford's Shelley Memorial, University College, Oxford. Commissioned in 1891.

Next up, entirely predictably, is one of the great abominations in the canon of Shelleyana - the famous (or infamous) Shelley Memorial at University College, Oxford. The history of this hardly bears repeating. It was so routinely disfigured and disrespected by young Oxford students that today it is actually encased in a cage. It was Shelley's daughter-in-law who perpetrated this imaginative, shambolic disaster. Paul Foot absolutely shreds this statue in his speech, "The Revolutionary Shelley"

Not content with this, she went further and commissioned Henry Weeks to reinvent Shelley as Christ and Mary as, well, another Mary. The resulting statute was, according to my father, refused by Westminister on the grounds of his atheism - if this anecdote is in any way true, I rather doubt his atheism had anything to do with it; more likely it was the monstrously poor taste in which the statue was executed. You be the judge:

Henry Weeks, Shelley Memorial, Christchurch Priory, Bournemouth, England

Shelley's birthplace, "Field Place", Horsham, Sussex.

It is now that the scrapbook becomes more interesting, for it becomes clear that my 19 year old father was engaged on a sort of pilgrimage, following in the footsteps of Shelley. The preceding pages feature postcards clearly acquired on a visit to Oxford in July of 1937; a visit clearly focused almost exclusively on Shelley. However, the previous year, and almost immediately upon his arrival in England, he traveled to Shelley's birthplace where he took a sequence of poorly composed but magical photographs:

There are thousands of beautiful pictures of Field Place; these are awful. But that is not the point. These photographs have a haunting, poignant, other-worldly quality. They were taken by an 18 year old boy who was enthralled by his hero, Shelley. And they take us back in time almost a century. He kept a very detailed diary of those years, and his thoughts and reflections in this pilgrimage are memorable and touching.

The graves of Mary, Mary Wollestonecraft, William Godwin, Percy Florence Shelley and the latter's wife, Jane Shelley

Dad also visited the graves of Mary, Mary Wollestonecraft, William Godwin, Percy Florence Shelley and the latter's wife, Jane Shelley. As he notes, "They are all in one plot of ground (barely sufficient for five people to die down)....One stone does for all." Interestingly, Mary had refused Trelawny's offer of the plot he had reserved for himself beside Shelley's grave in Rome. I have always found that curious, though none of Shelley's biographers offer any thoughts on this. Had she not refused, it would have been she and not Trelawny who is buried beside Shelley. This is, I think, a great loss; for more than one reason.

The home in Marlow in 1937

Prior to visiting Oxford in July of 1937, my father also dropped by Marlow to visit Shelley's home in that location. The pictures are somewhat clearer and he records the inscription above the dwelling which includes the line "...and was here visited by Lord Byron."

Lechlade, Gloucestershire, 1936

One of my father's favourite poems by Shelley was "Lechlade:A Summer-Evening Churchyard" so, of course he went there in 1936. In a chemist shop owned by a man named Davis, he was informed that according to local legend, Shelley had strolled through a particular path in the town composing the poem. The top photograph shows this path, the bottom, the neighbouring cathedral.

We now come to one of the more significant fabrications of literary history. The cremation of Shelley. Here is the painting by Louis Edward Fournier;

Louis Edward Fournier, "The Burning of Shelley", 1889.

It is not for me to debunk the many myths created by one of history's great liars, Edward John Trelawny (Bieri does an excellent job in his biography of Shelley). Shelley was indeed cremated by the bay of Lerici. The body had washed ashore after 10 days rotting in the ocean. It was thrown into a shallow grave and covered with lime. It was only over a month later that permission was finally received to exhume the body and cremate it - and what they found was horrific - the body was "badly mutilated, decomposed and destroyed." Mary was NOT at the burning and Byron refused to witness it himself. This painting, like so many of the other signal components of the Shelley myth, was hagiographic in tone and divorced from reality. But to an impressionable 19 year old Canadian on a pilgrimage in the footsteps of Shelley, it was as good as gold.

Upper right, Keats' tomb. Lower left, Trelawny, lower right, Shelley, Photographs 1950

The Second World War then stole almost 10 years from my father's life, as it did for so many millions more. He was lucky to be demobilized quickly and lucky again to find employment quickly. He became a journalist and rose very quickly to become the most famous Canadian broadcaster of his era. I will tell THIS story elsewhere. In 1950 he secured an extraordinary assignment. Tour the world and send stories back to Canadians eager to learn about strange an exotic locales. One of the places he went was Rome and it will surprise no one reading this that he made a beeline to the Protestant Cemetery and Shelley's grave.

The photographs are poorly composed and either under or over exposed. But again, they have an intensity, a nostalgia and a haunting quality which are undeniable. So many things strike me. why did my father have his picture taken at Keats' grave and not Shelley's? He had very little time for Keats. Why only a picture of the tombstone itself? I have been in the Cemetery. It is an extraordinary lace and it must have been even more extraordinary in 1950 when the world was literally bereft of tourists. The photograph of Shelley's grave, in many formats, graced our home through out my life. My father curiously never had it properly framed or preserved - and the negatives are long lost. But I treasure these images, the more so for their faded character, there soiled nature and their shop-worn corners.

Larry Henderson at Casa Magni, Lerici, Italy, September 1986

My father was a thorough man, and in 1986, as a vigorous 70 year old he made his way to the Bay of Lerici to visit the site of Shelley's death and his last domicile, the Casa Magni. Anna Mercer has made her own pilgrimage to Lerici, and her wonderful story, "In the Footsteps of the Shelleys" can be found here. He can be seen here, in one of his very typical poses, in front of Shelley's last home.

From his first pilgrimage in 1936, to his last 50 years later in 1986, my father was devoted to the man and the poet he perceived Shelley to be. While we could never find any common ground in our mutual appreciations for Shelley, which I wrote about in "My Father's Shelley: A Tale of Two Shelleys", I have come to realize that in his passion for Shelley, I am my father's son (and perhaps my grandmother's grandson!). I do not know if my father's and grandmother's love for this man will descend to another generation of Hendersons, but if it does not and if it ends here, it has be a truly memorable run. And were Shelley alive to have witnessed all this, as a man who believed that the world could indeed be changed one person at a time, I am hope he would be well and truly satisfied.

THE WIND has swept from the wide atmosphere

Each vapor that obscured the sunset’s ray;

And pallid Evening twines its beaming hair

In duskier braids around the languid eyes of Day.

Silence and Twilight, unbeloved of men,

Creep hand in hand from yon obscurest glen.

They breathe their spells toward the departing day,

Encompassing the earth, air, stars, and sea;

Light, sound, and motion own the potent sway,

Responding to the charm with its own mystery.

The winds are still, or the dry church-tower grass

Knows not their gentle motions as they pass.

Thou too, aerial pile, whose pinnacles

Point from one shrine like pyramids of fire,

Obeyest in silence their sweet solemn spells,

Clothing in hues of heaven thy dim and distant spire,

Around whose lessening and invisible height

Gather among the stars the clouds of night.

The dead are sleeping in their sepulchres;

And, mouldering as they sleep, a thrilling sound,

Half sense, half thought, among the darkness stirs,

Breathed from their wormy beds all living things around;

And, mingling with the still night and mute sky,

Its awful hush is felt inaudibly.

Thus solemnized and softened, death is mild

And terrorless as this serenest night;

Here could I hope, like some inquiring child

Sporting on graves, that death did hide from human sight

Sweet secrets, or beside its breathless sleep

That loveliest dreams perpetual watch did keep.

Percy Bysshe Shelley, drowned at sea, 8 July 1822.

"Death is mild and terrrorless as this serenest night."

My Father's Shelley; a Tale of Two Shelleys

My father’s Shelley, as I VERY quickly discovered, was very different from mine. He loved the lyric poet. He loved the Victorian version. He loved Mary’s sanitized version. In a weird way he bought into Mathew Arnold's caricature of Shelley (“a beautiful and ineffectual angel, beating his wings in a luminous void in vain.”) – and loved him the more for it. He hated the idea that Shelley was a revolutionary.

When I was very little, my father, dissatisfied with the state of my education, decided that he would offer Sunday evening lectures in his library. And so each Sunday, at exactly the time Bonanza was on, my brother and I would be herded into the library, moaning and complaining. A chalk board was produced. And the entire history of the Greek and Roman world played out, slowly, labouriously, on that chalk board over the ensuing years...or at least it seemed like years.

In addition to ancient history, recent poetry was assigned for memorization. When I say recent, I mean poetry from the 18th and 19th centuries. To this day, I have a little volume of around 20 poems that he gave to me – all specially selected. It was quite a cross-section.

We would actually be QUIZZED on poetry and history!! As if school wasn't bad enough. There were, however, incentives. I think we got 50 cents for every poem we could successfully recite. I recently found a little postcard that he sent home from one of his travels. It ended with a gentle admonition to make sure I had something new memorized for him upon his return. I discovered one of the quizzes years after his death. Have a look...how well would a 10-12 year old do today? -- how well would a university student do?!

Now as much as this grated on me when i was young, it did engender in me a love for classical culture and poetry. It also led to some amusing disagreements over the years. My father was deeply aggrieved, for example, that I failed to enshrine Pope's translation of the Iliad as the only translation worth having. On one visit to our home, he stood at my bookshelves gazing with open dismay on my collection of translations of the Iliad - at that time well over a dozen. He thought this was perverse. My wife ventured the thought that it must be wonderful to see a seed that he had planted grow to such fruition - but he was having none of it; I had sinned against Pope, the God of the Iliad. Weeks later, the issue was still occupying his thoughts. At a lunch with my brother, agitated, he put down his knife and fork and asked my brother what was wrong with me. Alexander Pope had been good enough for him (and by extension the entire world), why did I feel the need to venture afield and embrace these other pretenders: "Ross, what is wrong with Alexander Pope?" he lamented in his highly theatrical voice. What indeed?!

Later in life he also came down firmly on the side of the Greeks. Once, my brother gave him a book on the emperor Diocletian. Dad promptly returned the book unread, bitterly remarking upon Ross' and my putative adherence to Roman civilization - "The Romans," he remarked dismissively, "were nothing but bully-boys." But I digress.

As I grew up, like most boys, I actively sought out things to like and do that distanced me from my father. For example, I spent most of my high school years studying maths – a subject matter as alien to my father as any subject on earth. Then I went to University to be a geologist. Disaster. I finally dropped out and worked for a year or so, only to return to University where I ended up studying English Literature. I am not sure what it was that led me to Shelley. But something did…. perhaps the awful shadow of some unseen power. I went deeper and deeper: first an undergraduate thesis and then an MA thesis (undertaken under the supervision of that great Shelley scholar, Milton Wilson). I even started out on a PhD before I came to my senses.

Anyway, to the point. In those days, when one’s thesis was completed, they would bind up a couple of copies for you. Now by this point in my life, I have to confess, somewhat ruefully, that my father and I were barely on speaking terms. Nonetheless, like most young men, I still craved his approval. So, thesis in hand, I traveled to the family homestead to see my parents. Burning a hole in my briefcase was a copy of my thesis: “Prometheus Unbound and the Problem of Opposites.” (Hopefully soon to be published in this space!)

He was in his library. After spending sometime in the kitchen with my mum, I screwed up my nerve and knocked on the door. He called me in. As always, we had to stand at the door waiting for him to finish whatever thought it was that he was in the midst of jotting down. He was ALWAYS writing, furiously, on a clipboard. Finally, after what seemed an eternity, he looked up and said hello.

I explained what I was doing. I presented him with the thesis. And then something truly surreal happened; something that seared itself into my memory. Without really looking at it, he smiled absently, congratulated me and turned to walk toward his library shelves with my thesis. He casually remarked over his shoulder, “Thank you, Gra, I shall put it with the rest of my Shelleyana.”

Time slowed to a stop. I remember struggling to understand what that could mean. But my gaze followed his hands, up, up, up to the higher shelves. And there it was…sweet mother of god…maybe 10 linear FEET of books on Shelley.

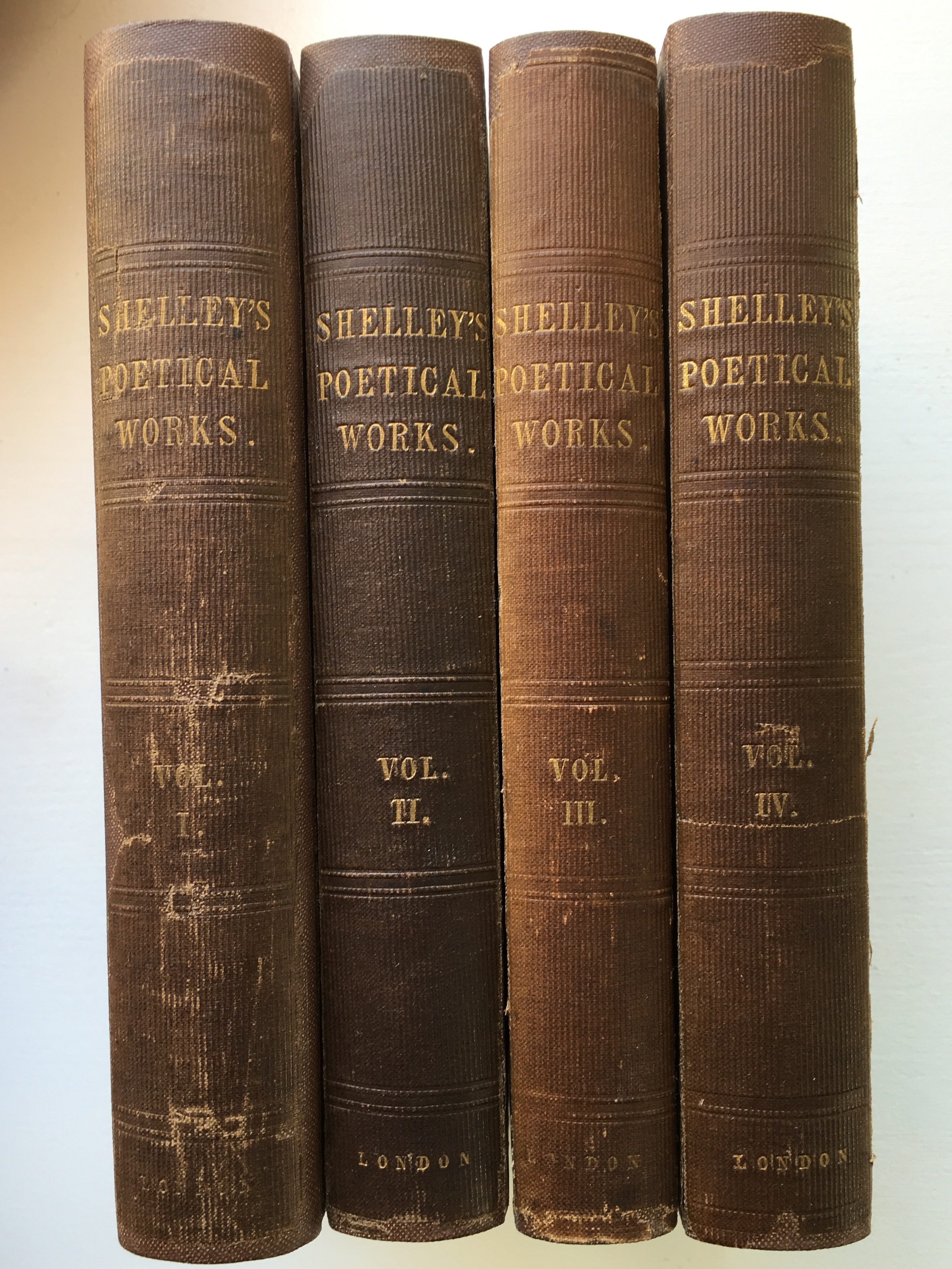

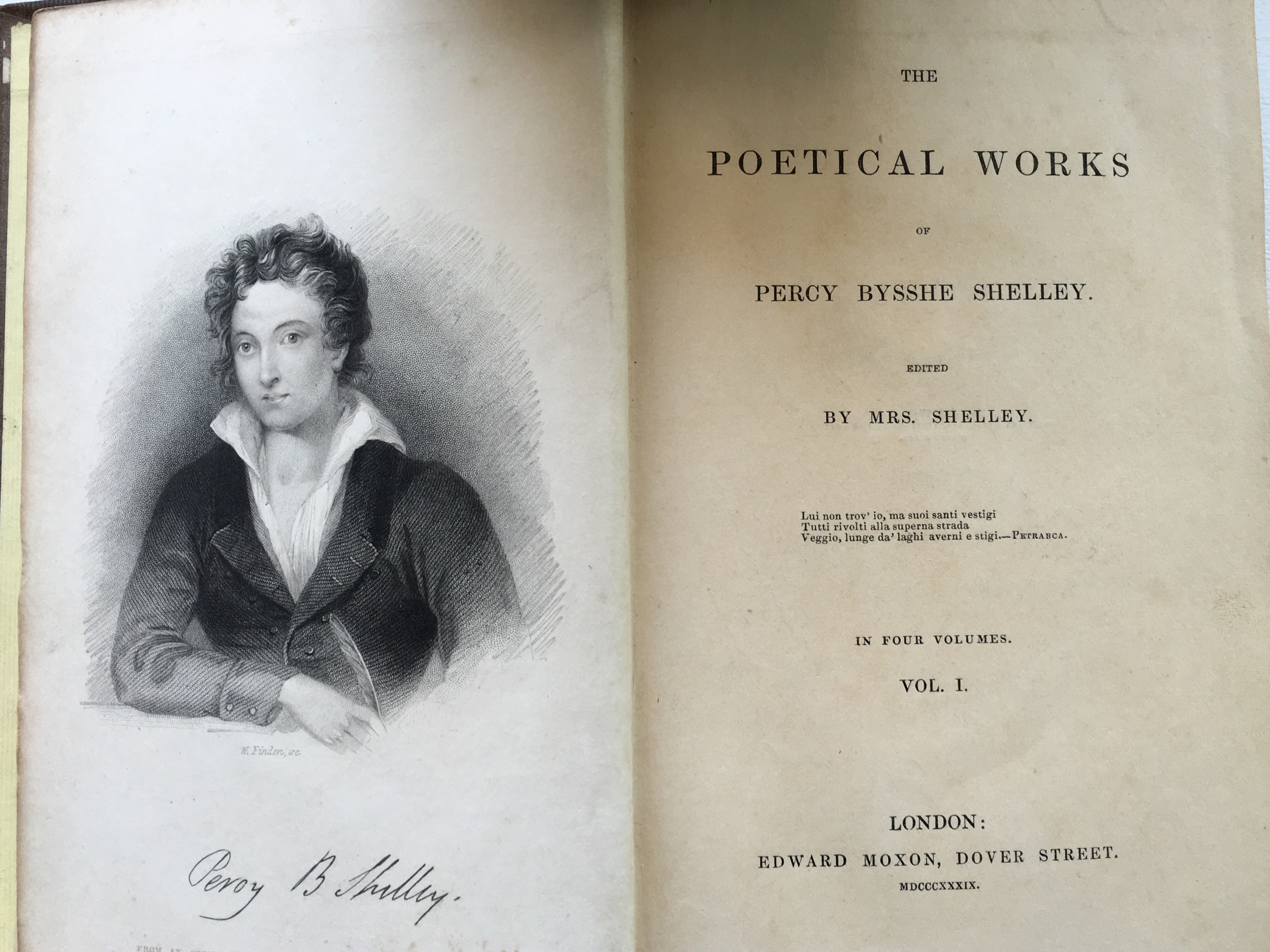

Approximately 1/3 of my father's "Shelleyana". Most of these books are first editions.

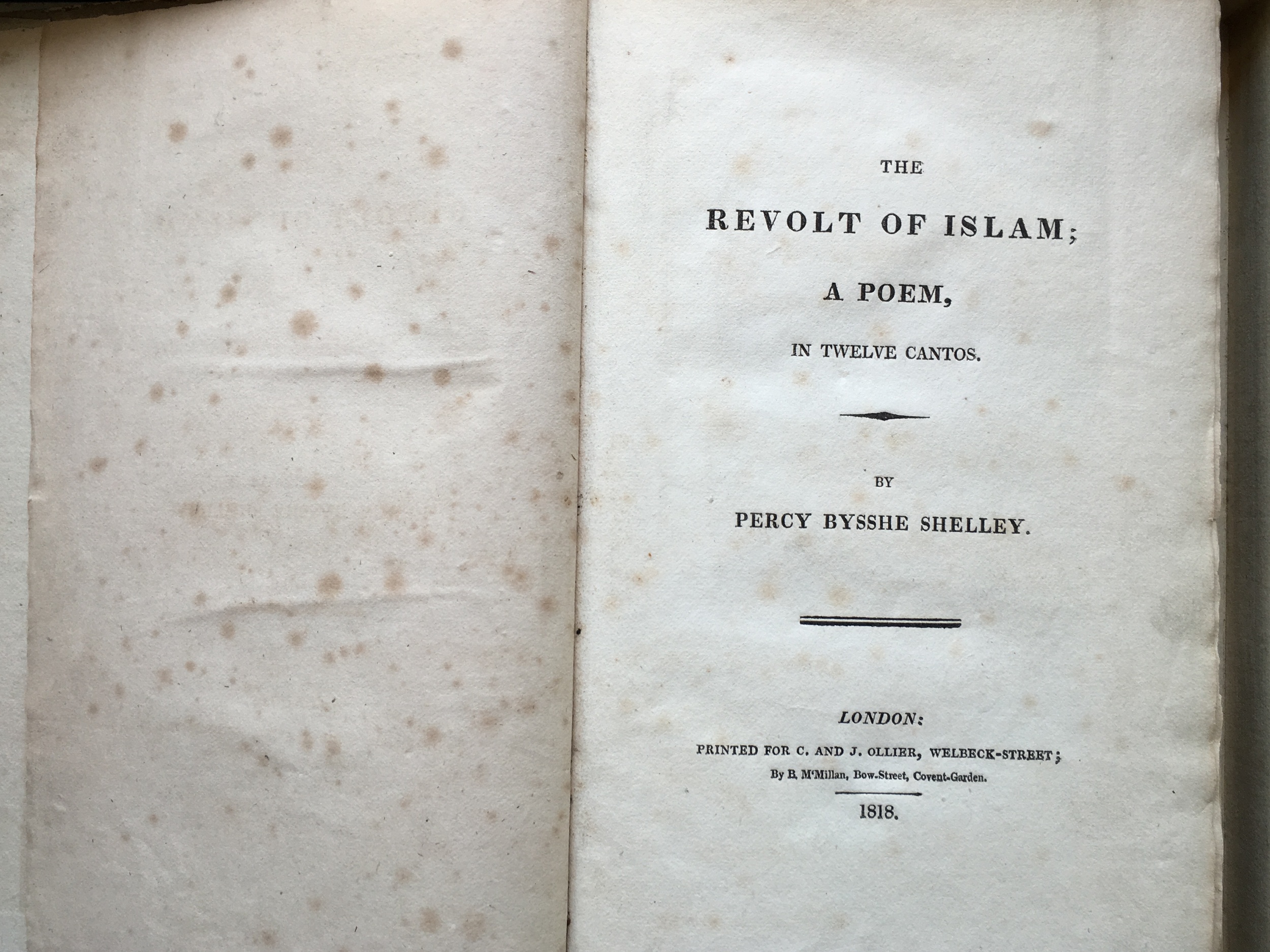

I did not realize at the time, but this collection also happened to include a first edition of “The Revolt of Islam” and the four volume 1839 Collected Works that Mary put out. I kid you not. In fact, it turned out that almost everything up there on those shelves was a first edition of some sort. It was like an Aladdin’s cave specially built for Shelley scholars. People like ME…people like…oh my god…my DAD!! Click on the image to see the slide show:

Inscription to my brother in Hutchinson's Collected Works of Shelley

Now in retrospect, none of this should have really been a big surprise. For starters, my brother’s middle name is Shelley (I am not sure he appreciated the choice as a boy). Dad had given him a copy Hutchinson's "The Complete Poetical Works of Shelley" (a gorgeous single volume, with gilt edged paper and blue calf skin binding) in 1956...AT AGE ONE!! It bore an inscription to my brother: 'The secret strength of things / Which governs thought, and to the infinite dome / Of heaven is as a law, inhabits thee!.'

My markups to Hutchinson's "Poetical Works of Shelley" -- given to my brother at age 1.

I knew this because it was this volume I had used throughout my entire course of Shelley studies.

And then, finally there was that other piece of evidence: there had been a Shelley poem in that little black volume I was given when I was around 10. As it turned out, Shelley was my father’s favourite poet. The man I barely spoke to, the man I had spent most of my life distancing myself from, was -- just like me -- devoted to Percy Bysshe Shelley. This was a sobering and disquieting revelation. As I reflect back on this, what I wonder is this: was it THAT poem? Was it Shelley's poem, the one he gave me to memorize, that planted the seed which flowered so many years later?

Well, before we get to that, I am afraid to say that it actually gets weirder. As I stood there, my jaw working, no sounds coming out of my mouth, he turned back to me and asked me what I meant by the “Problem of Opposites.” He asked if this was a reference to Jung, by any chance. By this time I knew where this is going -- there was an inevitability to it; there was an inexorable fate at work. He then gestured vaguely across the room at another shelf load of books. Yes, that’s right: The Complete Works of C.G. Jung. He asked if I would like to borrow any of them if I was continuing my studies on Jung and Shelley.

Because, of COURSE, that is EXACTLY what I had spent the better part of four years doing - applying Jungian theory to the study of Shelley's poetry.

I should point out that my approach to Shelley was so arcane and unique that my thesis supervisor, Milton Wilson, had a hard time drumming up professors to quiz me. It was niche to say the least. Yet somehow I had stumbled onto a course of study that duplicated two of my father's keenest interests.

Retreating from the library in some bemusement, I walked into the kitchen and my poor mother looked at me in dismay. “You look awful,” she said, “You look like you just saw a ghost. What happened in there?” Good question.

I can laugh about all of this now. But then? Not so much. I was young and desperate to be different.

As I sat at the kitchen table trying to sort through my emotions, I thought, “Well, at least, I now have something to talk to him about”. And so a desultory communication began. But this too soon turned into almost open warfare. My father’s Shelley, as I VERY quickly discovered, was very different from mine. He loved the lyric poet. He loved the Victorian version. He loved Mary’s sanitized version. In a weird way he bought into Mathew Arnold's caricature of Shelley (“a beautiful and ineffectual angel, beating his wings in a luminous void in vain.”) – and loved him the more for it. He hated the idea that Shelley was a revolutionary. I have an article coming on the truly remarkable evolution of Shelley's reputation - it is unlike almost another poet in history. Well, my father loved the Victorian version of Shelley, the version which led Engles to remark:

"Shelley, the genius, the prophet, finds most of [his] readers in the proletariat; the bourgeouise own the castrated editions, the family editions cut down in accordance with the hypocritical morality of today”

I once gave him a copy of Foot’s “The Red Shelley”. This was not well received. He hated the idea that Shelley was anything but the child-like construct of Francis Thompson:

“Enchanted child, born into a world unchildlike; spoiled darling of Nature, playmate of her elemental daughters; "pard-like spirit, beautiful and swift," laired amidst the burning fastnesses of his own fervid mind; bold foot along the verges of precipitous dream; light leaper from crag to crag of inaccessible fancies; towering Genius, whose soul rose like a ladder between heaven and earth with the angels of song ascending and descending it;--he is shrunken into the little vessel of death, and sealed with the unshatterable seal of doom, and cast down deep below the rolling tides of Time.”

We had heated arguments about this.

My father's marginalia in Santayana's short monograph on Shelley. "not a communist." Almost every statement Santayana makes on this page is completely incorrect,

As recently as a few months back, I was browsing through his library (he has been dead these past 9 years, but I have kept most of the library together – it is a reflection of his vast and complex mind). I pulled a slim volume from the Shelley shelves; one I had not looked at before. It was George Santayana’s short monograph on Shelley, "Shelley: Or the Poetic Value of Revolutionary Principles". My father was a fierce marker-up of books – another thing he seems to have bequeathed to me. I like flipping through his books to see what he underlined and what his comments were. I often get into arguments with his comments, writing my own in beside his. Anyway, half way through the essay, in one of the margins, were the words , “NOT A COMMUNIST” in a bold, firm, triumphant hand.

Now, my father was a big time anti-communist; he spent most of his life fighting the cold war and then refighting it after it was over. One of his great fears was that Shelley was some sort of communist! And of course, this EXACTLY what the communists thought he was! Marx:

"The real difference between Byron and Shelley is this: those who understand and love them rejoice that Byron died at 36, because if he had lived he would have become a reactionary bourgeois; they grieve that Shelley died at 29, because he was essentially a revolutionist and he would always have been one of the advanced guard of socialism."

But there, for my father, in the calming words of the great George Santayana, was solace and respite: no, Shelley was NOT a communist. Phew.

There can never be a resolution between these two visions of Shelley. My father's Shelley was a Shelley built on false foundations, willful misreadings and wishful thinking. He, and others like him, created a mythical version, so far removed from the historical Shelley that it is scarcely believable. The way in which this awful perversion of history took place is concisely covered in Michael Gamer's article, “Shelley Incinerated.” (The Wordsworth Circle 39.1/2 (2008): 23-26.) I intend to canvas the issues more fully at a future date.

It saddens me that our two Shelleys were separated by an unbridgeable chasm. But I have to always remember that my Shelley could never have come to life had not my father, in a very different time and place, conceived his own Shelley, and fallen in love with him and endeavoured to convey that passion to his children.

But how about that poem? The poem that may have planted the seed of which I was utterly unaware. What exactly was the Shelley poem in that little binder he had given to me at age 9 or 10? I know it by heart to this very day. It was this:.

Arethusa arose

From her couch of snows

In the Acroceraunian mountains,--

From cloud and from crag,

With many a jag,

Shepherding her bright fountains.

She leapt down the rocks,

With her rainbow locks

Streaming among the streams;--

Her steps paved with green

The downward ravine

Which slopes to the western gleams;

And gliding and springing

She went, ever singing,

In murmurs as soft as sleep;

The Earth seemed to love her,

And Heaven smiled above her,

As she lingered towards the deep.

II.

Then Alpheus bold,

On his glacier cold,

With his trident the mountains strook;

And opened a chasm

In the rocks—with the spasm

All Erymanthus shook.

And the black south wind

It unsealed behind

The urns of the silent snow,

And earthquake and thunder

Did rend in sunder

The bars of the springs below.

And the beard and the hair

Of the River-god were

Seen through the torrent’s sweep,

As he followed the light

Of the fleet nymph’s flight

To the brink of the Dorian deep.

III.

'Oh, save me! Oh, guide me!

And bid the deep hide me,

For he grasps me now by the hair!'

The loud Ocean heard,

To its blue depth stirred,

And divided at her prayer;

And under the water

The Earth’s white daughter

Fled like a sunny beam;

Behind her descended

Her billows, unblended

With the brackish Dorian stream:—

Like a gloomy stain

On the emerald main

Alpheus rushed behind,--

As an eagle pursuing

A dove to its ruin

Down the streams of the cloudy wind.

IV.

Under the bowers

Where the Ocean Powers

Sit on their pearled thrones;

Through the coral woods

Of the weltering floods,

Over heaps of unvalued stones;

Through the dim beams

Which amid the streams

Weave a network of coloured light;

And under the caves,

Where the shadowy waves

Are as green as the forest’s night:--

Outspeeding the shark,

And the sword-fish dark,

Under the Ocean’s foam,

And up through the rifts

Of the mountain clifts

They passed to their Dorian home.

V.

And now from their fountains

In Enna’s mountains,

Down one vale where the morning basks,

Like friends once parted

Grown single-hearted,

They ply their watery tasks.

At sunrise they leap

From their cradles steep

In the cave of the shelving hill;

At noontide they flow

Through the woods below

And the meadows of asphodel;

And at night they sleep

In the rocking deep

Beneath the Ortygian shore;--

Like spirits that lie

In the azure sky

When they love but live no more.

Well chosen, Dad, well chosen; and thank you for this great gift (thanks also for not giving ME the middle name, Shelley!).

- Aeschylus

- Amelia Curran

- Anna Mercer

- Arethusa

- Arielle Cottingham

- Atheism

- Byron

- Charles I

- Chartism

- Cian Duffy

- Claire Clairmont

- Coleridge

- Defense of Poetry

- Diderot

- Douglas Booth

- Earl Wasserman

- Edward Aveling

- Edward Silsbee

- Edward Trelawny

- Edward Williams

- England in 1819

- Engles

- Francis Thompson

- Frank Allaun

- Frankenstein

- Friedrich Engels

- George Bernard Shaw

- Gerald Hogle

- Harold Bloom

- Henry Salt

- Honora Becker

- Hotel de Villes de Londres

- Humanism

- James Bieri

- Jeremy Corbyn

- Karl Marx

- Kathleen Raine

- Keats-Shelley Association

- Kenneth Graham

- Kenneth Neill Cameron

- La Spezia

- Larry Henderson

- Leslie Preger

- Lucretius

- Lynn Shepherd

- Mark Summers

- Martin Priestman

- Marx

- Marxism

- Mary Shelley

- Mary Sherwood

- Mask of Anarchy

- Michael Demson

- Michael Gamer

- Michael O'Neill

- Michael Scrivener

- Milton Wilson

- Mont Blanc

- Neccessity of Atheism

- Nora Crook

- Ode to the West Wind

- Ozymandias

- Paul Foot

- Paul Stephens

- Pauline Newman

- Percy Shelley

- Peter Bell the Third

- Peterloo

- Philanthropist

- philanthropos tropos

- PMS Dawson

- Political Philosophy

- Prince Athanese

- Prometheus Unbound

- Queen Mab

- Richard Holmes

- romantic poetry

- Ross Wilson

- Sandy Grant

- Sara Coleridge

- Sarah Trimmer

- Scientific Socialism

- Shelleyana

- Skepticism

- Socialism

- Song to the Men of England

- Stopford Brooke

- Tess Martin

- The Cenci

- The Mask of Anarchy

- The Red Shelley

- Timothy Webb

- Tom Mole

- Triumph of Life

- Victorian Morality

- Villa Diodati

- William Godwin

- William Michael Rossetti

- Wordsworth

- Yvonne Kapp