Atheist, Lover of Humanity, Democrat

PERCY BYSSHE SHELLEY

"I am a Lover of Humanity, a Democrat and an Atheist.” What did Shelley Mean?

The "catch phrase" I have used for the Shelley section of my blog ("Atheist. Lover of Humanity. Democrat.") may require some explanation. The words originated with Shelley himself, but when did he write it, where did he write it and most important why did he write it. Many people have sought to diminish the importance of these words and the circumstances under which they were written. Some modern scholars have even ridiculed him. I think his choice of words was very deliberate and central to how he defined himself and how wanted the world to think of him. They may well have been the words he was most famous (or infamous) for in his lifetime.Five explosive little words that harbour a universe of meaning and significance.

Part of a new feature at www.grahamhenderson.ca is my "Throwback Thursdays". Going back to articles from the past that were favourites or perhaps overlooked. This was my first article for this site and it was published at a time when the Shelley Nation was in its infancy. I have noted how few folks have had a chance to have a look at it. And so I am taking this opportunity to take it out for another spin. If you have seen it, why not share it, if you have not seen it, I hope you enjoy it!

The "catch phrase" I have used for the Shelley section of my blog ("Atheist. Lover of Humanity. Democrat.") may require some explanation. The words originated with Shelley himself, but when did he write it, where did he write it and most important why did he write it. Many people have sought to diminish the importance of these words and the circumstances under which they were written. Some modern scholars have even ridiculed him. I think his choice of words was very deliberate and central to how he defined himself and how wanted the world to think of him. They may well have been the words he was most famous (or infamous) for in his lifetime.

Shelley’s atheism and his political philosophy were at the heart of his poetry and his revolutionary agenda (yes, he had one). Our understanding of Shelley is impoverished to the extent we ignore or diminish its importance.

Shelley visited the Chamonix Valley at the base of Mont Blanc in July of 1816.

"The Priory" Gabriel Charton, Chamonix, 1821

Mont Blanc was a routine stop on the so-called “Grand Tour.” In fact, so many people visited it, that you will find Shelley in his letters bemoaning the fact that the area was "overrun by tourists." With the Napoleonic wars only just at an end, English tourists were again flooding the continent. While in Chamonix, many would have stayed at the famous Hotel de Villes de Londres, as did Shelley. As today, the lodges and guest houses of those days maintained a “visitor’s register”; unlike today those registers would have contained the names of a virtual who’s who of upper class society. Ryan Air was not flying English punters in for day visits. What you wrote in such a register was guaranteed to be read by literate, well connected aristocrats - even if you penned your entry in Greek – as Shelley did.

The words Shelley wrote in the register of the Hotel de Villes de Londres (under the heading "Occupation") were (as translated by PMS Dawson): “philanthropist, an utter democrat, and an atheist”. The words were, as I say, written in Greek. The Greek word he used for philanthropist was "philanthropos tropos." The origin of the word and its connection to Shelley is very interesting. Its first use appears in Aeschylus’ “Prometheus Bound” the Greek play which Shelley was “answering” with his masterpiece, Prometheus Unbound. Aeschylus used his newly coined word “philanthropos tropos” (humanity loving) to describe Prometheus. The word was picked up by Plato and came to be much commented upon, including by Bacon, one of Shelley’s favourite authors. Bacon considered philanthropy to be synonymous with "goodness", which he connected with Aristotle’s idea of “virtue”.

What do the words Shelley chose mean and why is it important? First of all, most people today would shrug at his self-description. Today, most people share democratic values and they live in a secular society where even in America as many as one in five people are unaffiliated with a religion; so claiming to be an atheist is not exactly controversial today. As for philanthropy, well, who doesn’t give money to charity, and in our modern society, the word philanthropy has been reduced to this connotation. I suppose many people would assume that things might have been a bit different in Shelley’s time – but how controversial could it be to describe yourself in such a manner? Context, it turns out, is everything. In his time, Shelley’s chosen labels shocked and scandalized society and I believe they were designed to do just that. Because in 1816, the words "philanthropist, democrat and atheist" were fighting words.

Shelley would have understood the potential audience for his words, and it is therefore impossible not to conclude that Shelley was being deliberately provocative. In the words of P.M.S. Dawson, he was “nailing his colours to the mast-head”. As we shall see, he even had a particular target in mind: none other than Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Word of the note spread quickly throughout England. It was not the only visitor’s book in which Shelley made such an entry. It was made in at least two or three other places. His friend Byron, following behind him on his travels, was so concerned about the potential harm this statement might do, that he actually made efforts to scribble out Shelley’s name in one of the registers.

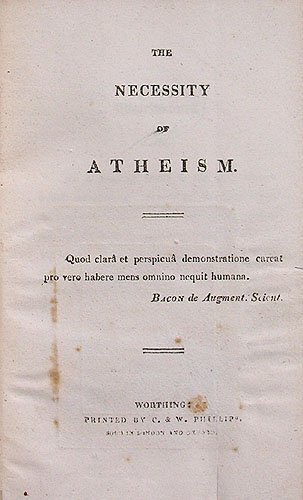

While Shelley was not a household name in England, he was the son of an aristocrat whose patron was one of the leading Whigs of his generation, Lord Norfolk. Behaviour such as this was bound to and did attract attention. Many would also have remembered that Shelley had been actually expelled from Oxford for publishing a notoriously atheistical tract, The Necessity of Atheism.

Shelley's pamphlet, "The Necessity of Atheism"

While his claim to be an atheist attracted most of the attention, the other two terms were freighted as well. Democrat then had the connotations it does today but such connotations in his day were clearly inflammatory (the word “utter” acting as an exclamation mark). The term philanthropist is more interesting because at that time it did not merely connote donating money, it had overt political and even revolutionary overtones. To be an atheist or a philanthropist or a democrat, and Shelley was all three, was to be fundamentally opposed to the ruling order and Shelley wanted the world to know it.

What made Shelley’s atheism even more likely to occasion outrage was the fact that English tourists went to Mont Blanc specifically to have a religious experience occasioned by their experience of the “sublime.” Indeed, Timothy Webb speculates that at least one of Shelley’s entries might have been in response to another comment in the register which read, “Such scenes as these inspires, then, more forcibly, the love of God”. If not in answer to this, then most certainly Shelley was responding to Coleridge, who, in his head note to “Hymn Before Sunrise, in the Vale of Chamouni,” had famously asked, “Who would be, who could be an Atheist in this valley of wonders?" In a nutshell Shelley's answers was: "I could!!!"

Mont Blanc, 16 May 2016, Graham Henderson

The reaction to Shelley’s entry was predictably furious and focused almost exclusively on Shelley’s choice of the word “atheist”. For example, this anonymous comment appeared in the London Chronicle:

Mr. Shelley is understood to be the person who, after gazing on Mont Blanc, registered himself in the album as Percy Bysshe Shelley, Atheist; which gross and cheap bravado he, with the natural tact of the new school, took for a display of philosophic courage; and his obscure muse has been since constantly spreading all her foulness of those doctrines which a decent infidel would treat with respect and in which the wise and honourable have in all ages found the perfection of wisdom and virtue.

Shelley’s decision to write the inscription in Greek was even more provocative because as Webb points out, Greek was associated with “the language of intellectual liberty, the language of those courageous philosophers who had defied political and religious tyranny in their allegiance to the truth."

The concept of the “sublime” was one of the dominant (and popular) subjects of the early 19th Century. It was widely believed that the natural sublime could provoke a religious experience and confirmation of the existence of the deity. This was a problem for Shelley because he believed that religion was the principle prop for the ruling (tyrannical) political order. As Cian Duffy in Shelley and the Revolutionary Sublime has suggested, Prometheus Unbound, like much of his other work, “was concerned to revise the standard, pious or theistic configuration of that discourse [on the natural sublime] along secular and politically progressive lines...." Shelley believed that the key to this lay in the cultivation of the imagination. An individual possessed of an “uncultivated” imagination, would contemplate the natural sublime in a situation such as Chamonix Valley, would see god at work, and this would then lead inevitably to the "falsehoods of religious systems." In Queen Mab, Shelley called this the "deifying" response and believed it was an error that resulted from the failure to 'rightly' feel the 'mystery' of natural 'grandeur':

"The plurality of worlds, the indefinite immensity of the universe is a most awful subject of contemplation. He who rightly feels its mystery and grandeur is in no danger of seductions from the falsehoods of religious systems or of deifying the principle of the universe” (Queen Mab. Notes, Poetical Works of Shelley, 801).

He believed that a cultivated imagination would not make this error.

This view was not new to Shelley, it was shared, for example, by Archibald Alison whose 1790 Essays on the Nature and Principles of Taste made the point that people tended to "lose themselves" in the presence of the sublime. He concluded, "this involuntary and unreflective activity of the imagination leads intentionally and unavoidably to an intuition of God's presence in Creation". Shelley believed this himself and theorized explicitly that it was the uncultivated imagination that enacted what he called this "vulgar mistake." This theory comes to full fruition in Act III of Prometheus Unbound where, as Duffy notes,

“…their [Demogorgon and Asia] encounter restates the foundational premise of Shelley’s engagement with the discourse on the natural sublime: the idea that natural grandeur, correctly interpreted by the ‘cultivated imagination, can teach the mind politically potent truths, truths that expose the artificiality of the current social order and provide the blueprint for a ‘prosperous’, philanthropic reform of ‘political institutions’.

Shelley’s atheism was thus connected to his theory of the imagination and we can now understand why his “rewriting” of the natural sublime was so important to him.

If Shelley was simply a non-believer, this would be bad enough, but as he stated in the visitor’s register he was also a “democrat;” and by democrat Shelley really meant republican and modern analysts have now actually placed him within the radical tradition of philosophical anarchism. Shelley made part of this explicit when he wrote to Elizabeth Hitchener stating,

“It is this empire of terror which is established by Religion, Monarchy is its prototype, Aristocracy may be regarded as symbolizing its very essence. They are mixed – one can now scarce be distinguished from the other” (Letters of Shelley, 126).

This point is made again in Queen Mab where Shelley asserts that the anthropomorphic god of Christianity is the “the prototype of human misrule” (Queen Mab, Canto VI, l.105, Poetical Works of Shelley, 785) and the spiritual image of monarchical despotism. In his book Romantic Atheism, Martin Priestman points out that the corrupt emperor in Laon and Cythna is consistently enabled by equally corrupt priests. As Paul Foot avers in Red Shelley, "Established religions, Shelley noted, had always been a friend to tyranny”. Dawson for his part suggests, “The only thing worse than being a republican was being an atheist, and Shelley was that too; indeed, his atheism was intimately connected with his political revolt”.

Three explosive little words that harbour a universe of meaning and significance.

Percy Bysshe Shelley In Our Time.

MASSIVE, NON-VIOLENT PROTEST. FROM SHELLEY TO #WOMENSMARCH

Shelley imagines a radical reordering of our world. It starts with us. Are we up for the challenge? Shelley was. Take the closing words of Prometheus Unbound and print them out. Pin them to your fridge, memorize them, share them with loved ones and enemies alike. Let them inspire you. Let them change you. And never forget he was 27 when he wrote these words and dead with in three years.

Shelley, who among poets was one of the most supremely political animals, described the condition of England in 1819 in a manner which should make us fear for our future. Around the globe tyrants and demagogues are taking power or going mainstream and entire civilizations are subject to theocratic dictatorships. If we don't want our future to look like this, we will need to organize and resist:

An old, mad, blind, despised, and dying King;

Princes, the dregs of their dull race, who flow

Through public scorn,—mud from a muddy spring;

Rulers who neither see nor feel nor know,

But leechlike to their fainting country cling

Till they drop, blind in blood, without a blow.

A people starved and stabbed in th' untilled field;

An army, whom liberticide and prey

Makes as a two-edged sword to all who wield;

Golden and sanguine laws which tempt and slay;

Religion Christless, Godless—a book sealed;

A senate, Time’s worst statute, unrepealed—

Are graves from which a glorious Phantom may

Burst, to illumine our tempestuous day.

England 1819, Percy Bysshe Shelley

Jonathan Freedland, writing in the Guardian, has some surprisingly Shelleyan proposals and suggestions to avoid this potential future. The Guardian's coverage has in general been superb. This can be contrasted with some of the coverage of Trump's inauguration address in the New York Times. One article (see insert) referred to Trump’s demagogic, xenophobic anti-intellectual inaugural diatribe as “forceful.” This is a disgraceful, shameful euphemism.

Freedland, and the Guardian, on the other hand have called a spade a spade.

What fascinated me about Freedland’s article was the language he used. It struck me as distinctly reminiscent of Shelley – particularly in the many passages that focus on resistance and nonviolent protest. It was redolent of the Mask of Anarchy:

"So what should those who have long dreaded this moment do now? For some, the inauguration marks the launch of what they’re already calling “the resistance”, as if they are facing not just an unloved government but a tyranny. Note the banner held aloft by one group of demonstrators that read simply: “Fascist.”

"Placards and protests will have their place in the next four years. But those who want to stand in Trump’s way will need to do more than simply shake their fists. The work of opposition starts now."

And if people don’t think that what we are facing is a potential tyranny, we need look no further than the fact that Trump began signing executive orders immediately – the first one designed to role back the Affordable Care Act. Neither arm of the government has even had the opportunity to consider how to do this or with what what it should be replaced. In addition, he has ordered the creation of a missile defense system aimed squarely at southeast Asia, and created a new national holiday to celebrate “patriotism” – a euphemism no doubt for his own for Trumpian brand of xenophobic jingoism. Are you worried yet? This is day ONE.

Freedland goes on to set out what he sees are the principal ways opposition to Trump can be organized:

“At the front of the queue, as it were, are the press. There’s no doubt Trump sees it that way. With Clinton out of the way, the media has become his enemy of choice. The media’s very existence seems to infuriate him. Perhaps because it’s now the only centre of power he doesn’t control. With the White House and Congress in Republican hands, and the casting vote on the supreme court an appointment that’s his to make, it’s no wonder the fourth estate rankles: he already controls the other three.

That puts a great burden of responsibility on the press. Trump has majorities in the House and Senate, so often it will fall to reporters to ask the tough questions and hold the president to account. And it won’t be easy, if only because war against Trump is necessarily a war on many fronts. Just keeping up with his egregious conflicts of interests could be a full-time job, to say nothing of his bizarre appointments, filling key jobs with those who are either unqualified or actively hostile to the mission of the departments they now head. It’s a genuine question whether the media has sufficient bandwidth to cope.”

I agree on all counts. And we would do well to ruminate on one of the many reasons we are in this mess in the first place. We are here because Silicon Valley’s right wing brand of cyberlibertarianism has attacked some of the very foundations of our democracy and marginalized the left. The media has been hamstrung. And while we still have vibrant top-line outlets such as the Guardian and the NYTimes, local news has virtually ceased to exist. And social media has simply NOT replaced this – a point Freedland also makes. I think we need to usher in an era of mass civil disobedience and protest and that includes fighting back at corporations like Google who seek to dominate the way we see the world. My message to Millennials would be to remind them that, no, you do not simply have to accept things the way they are and slavishly follow brands. Once upon a time it was cool to say “fuck you” to corporations and “the man.” Here is Freedland:

“But that will count for nothing if there is not a popular movement of dissent, one that exists in the real world beyond social media. Some believe the mass rally is about to matter more than ever. Trump, remember, is a man who gets his knowledge of the world from television, and who is obsessed by ratings. How better to convey to him the public mood of disapproval than by forcing him to see huge crowds on TV, comprised of people who reject him?

And this will have to be backed by serious, organized activism. The left can learn from the success of the Tea Party movement, which did so much to obstruct Barack Obama. That will force congressional Democrats to consider whether they too should learn from their Republican counterparts, thwarting Trump rather than enabling him."

The title of Freedland’s article is this:

"Divisive, ungracious, unrepentant: this was Trump unbound"

Peter Paul Reubens, Prometheus Unbound. 1611-12.

I am fascinated by this because it seems to be a possibly ironical reference to Shelley's great poem, Prometheus Unbound whose villain, Jupiter shares many characteristics with Trump. In Shelley’s poem, however, it is the hero, Prometheus, who is unbound and overthrows Jupiter. Here it is the forces of darkness that have been unbound. Prometheus Unbound is a mythic drama, so we should not look to it for the sort of political commentary we saw in his short poem England 1819, quoted above. But it does have some startling imagery which describes the sort of world we could live into if we stand by and let fascists like Trump assume total control. The poem opens with a sort of monologue in which the hero, Prometheus, is speaking to Jupiter (Zeus). Prometheus describes a world:

Made multitudinous with thy slaves, whom thou

Requitest for knee-worship, prayer, and praise,

And toil, and hecatombs of broken hearts,

With fear and self-contempt and barren hope.

There are some wonderful touches here and does the description of Jupiter not fit the thin-skinned, praise-seeking Trump perfectly? What a great phrase: “knee-worship” -- is that not exactly what Trump seeks from his “deplorables” in fact from all of us? And isn’t the phrase “hecatombs of broken hearts” gorgeous! The word hecatomb refers to an ancient Greek practice of sacrificing an enormous number of oxen and has come to mean an extensive loss of life for some cause. Here Shelley harnesses the term to conjure an image of a world filled with people who are afraid, who have given up and whose hearts are broken – pointless sacrificed.

The most important insight that comes, however, from Prometheus Unbound, is that we create our own monsters; that we enslave ourselves. And when we think of how Trump became President, I think it is important that we agree that in many ways we are all responsible for this.

Hotel Reigister from Chamonix in which Shelley declared himself to be an atheist and "lover of mankind."

Shelley had also famously declared that he was a "lover of humanity, a democrat and atheist.” I have written about this here and here. These are words of enormous power and significance; then as now. The words, "lover of humanity", however, deserve particular attention. Shelley did not write these words in English, he wrote them in Greek: 'philanthropos tropos". This was deliberate. The first use of this term appears in Aeschylus’ play “Prometheus Bound”. This was the ancient Greek play which Shelley was “answering” with his own masterpiece, Prometheus Unbound.

Aeschylus uses his newly coined word “philanthropos tropos” (humanity loving) to describe Prometheus. The word was picked up by Plato and came to be much commented upon, including by Bacon, one of Shelley’s favourite authors. Bacon considered philanthropy to be synonymous with "goodness", which he connected with Aristotle’s idea of “virtue”. Shelley must have known this and I believe this tells us that Shelley was self-identifying with his own poetic creation, Prometheus.

Shelley had deliberately, intentionally and provocatively “nailed his colours to the mast” knowing full well his words would be widely read and would inflame passions. So, when he wrote those words, what did he mean to say? He meant this I think:

I am against god.

I am against the king.

I am the modern Prometheus.

And I will steal the fire of the gods and I will bring down thrones and I will empower the people.

No wonder he was considered a threat.

Not only did he say these things, he developed a system to deliver on this promise.

Part of his system was based on his innate skepticism, of which he was a surprisingly sophisticated practitioner. And like all skeptics since the dawn of history, he used it to undermine authority and attack truth claims. As he once said, "Implicit faith and fearless inquiry have in all ages been irreconcilable enemies. Unrestrained philosophy in every age opposed itself to the reveries of credulity and fanaticism."

Let us now talk a little about his political theory and bring ourselves up to the present.

"And who are those chained to the car?" "The Wise,

"The great, the unforgotten: they who wore

Mitres & helms & crowns, or wreathes of light,

Signs of thought's empire over thought; their lore

"Taught them not this—to know themselves; their might

Could not repress the mutiny within,

And for the morn of truth they feigned, deep night

"Caught them ere evening."

Triumph of Life 208 – 15

These words are from his last great poem. We see in this passage a succession of military, civil and political leaders all chained to a triumphal car of the sort Roman generals were fond using when they celebrated victory.

The triumph of Lucius Aemellias Paullus

But Shelley adds a twist. In his poem, these rulers are now themselves slaves. This helps us understand a curious idea of Shelley’s which has confused many of his readers. And that is the idea that the tyrant who enslaves men is himself becomes a slave. This is because they are slaves to all their baser instincts. We can clearly see Trump in this picture. As the character Asia shrewdly notes in Act II of Prometheus Unbound: “All spirits are enslaved who serve things evil.”

Now, Shelley saw a way to avoid this. And it is tied closely to his theory of the imagination and his understanding of the nature of people. Shelley believed that we did not have to be slaves of our baser instincts the way Trump is. His cure is the education of the imagination; something it is difficult to imagine Trump having ever undertaken as it is widely believed he has almost never read a book.

The great Shelley scholar, PMS Dawson wrote that Shelley believed “the world must be transformed in imagination before it can be changed politically.” This imaginative recreation of existence is, said Dawson, both the subject and the intended effect of Prometheus Unbound.

This is a wonderful idea: Shelley’s poem not only maps out a scheme to reinvent ourselves and therefore change to world, but also, simply by reading the poem we will have started out on our journey. This underlines the importance of the arts to making our world a better place. I think of Obama’s statements about the importance of books to him while he held the presidency. And then I think of the rumours that Trump intends to act to wipe out support for the arts. I think of the manner in which the right wing cyberlibertarian “religion” of silicon valley has attacked the very foundation of art – the ability of our creators to earn a decent living.

One of the central teachings of Prometheus Unbound then is that only someone devoid of the liberty of self-rule can become a tyrant and enslave others. Gaining control over our baser instincts therefore becomes central to the advancement of society (this also explains why Shelley clung so tenaciously to his idea of the perfectability of humanity. In Act III of the poem we clearly see the protagonist’s ascent to the “autonomy of self-rule” as an example for mankind to follow.

Finden's reimagining of Shelley drawn from the Curran portrait.

Shelley’s purpose in all his poetry is to help us (or cause us) to enlarge our imaginative apprehension of the world to such a point that there are no limits or inescapable evils. I think he believed that this is the role of all art. We need to be able to see different worlds, alternate worlds so that we can order our own world more equitably. Contrast this with Trump’s barbaric cry that America is only for Americans and that he will implement strategies which will benefit only Americans. This type of xenophobia, coupled with what amounts to a war on knowledge and the arts, is designed to create an environment in which tyranny becomes perpetual.

Shelley, however, is not a poet of gloom and dystopia. Shelley believed in humanity, he believed that we all have in us the power to be better and to make a better world. Indeed, the whole of Act 4 of Prometheus Unbound celebrates man’s birth into a universe that is alive because it is apprehended imaginatively.

Shelley did not, however think this would happen overnight. He was a gradualist, though I think even he would be surprised at just how gradual change can be. I often think that the thing which would shock him most about our modern world is not rockets and computers, but the fact we are still living in a priest and tyrant ridden world in which wealth is concentrated more than ever in a few hands. But he also believed that in moments of crisis, progress can emerge from conflict. Which is exactly where we are now. Exactly how we extract progress from our current crisis is up to us.

But I hope that we can see a glimpse of the future in these extraordinary pictures from around the world of the massive women's marches. Women are employing the very tactics that Shelley proposed two centuries ago:

'And these words shall then become

Like Oppression's thundered doom

Ringing through each heart and brain,

Heard again-again-again-

'Rise like Lions after slumber

In unvanquishable number-

Shake your chains to earth like dew

Which in sleep had fallen on you-

Ye are many-they are few.'

These words have inspired generation of protesters and leaders, including Gandhi. Today, as Freedland also points out, the threats are so multifaceted that they threaten to overwhelm us. As facile as this might sound, I think we need to believe in ourselves and in human nature. We need to resist, we need to organize, we need to keep the arts alive. It will not be easy. This is a theme explored by Michael Demson in his graphic novel that celebrated Shelley other great political poem, The Mask of Anarchy. I reviewed it here.

At the end of Prometheus Unbound come three stanzas of the most exquisite poetry ever written. In the first stanza Shelley forecasts the end of tyranny. He sees an abyss that yawns and swallows up despotism. And he sees love as transcendent. Now the moment we start to talk about the role of "love" in this I think some people might roll their eyes. But don’t. Shelley is thinking more about empathy than romantic love here. And nurturing empathy within us may be one of the greatest challenges our time. Certainly, Trump and his “lovely deplorables” have utterly failed in this regard. Shelley then goes on to itemize the psychological characteristics which will ensure that the tyrant once deposed, does not return.

Shelley imagines a radical reordering of our world. It starts with us. Are we up for the challenge? Shelley was. Take the closing words of Prometheus Unbound and print them out. Pin them to your fridge, memorize them, share them with loved ones and enemies alike. Let them inspire you. Let them change you. And never forget he was 27 when he wrote these words and dead with in three years:

This is the day, which down the void abysm

At the Earth-born's spell yawns for Heaven's despotism,

And Conquest is dragged captive through the deep:

Love, from its awful throne of patient power

In the wise heart, from the last giddy hour

Of dread endurance, from the slippery, steep,

And narrow verge of crag-like agony, springs

And folds over the world its healing wings.

Gentleness, Virtue, Wisdom, and Endurance,

These are the seals of that most firm assurance

Which bars the pit over Destruction's strength;

And if, with infirm hand, Eternity,

Mother of many acts and hours, should free

The serpent that would clasp her with his length;

These are the spells by which to reassume

An empire o'er the disentangled doom.

To suffer woes which Hope thinks infinite;

To forgive wrongs darker than death or night;

To defy Power, which seems omnipotent;

To love, and bear; to hope till Hope creates

From its own wreck the thing it contemplates;

Neither to change, nor falter, nor repent;

This, like thy glory, Titan, is to be

Good, great and joyous, beautiful and free;

This is alone Life, Joy, Empire, and Victory.

Shelley's poetry has changed the world before; let them change it again.

- Aeschylus

- Amelia Curran

- Anna Mercer

- Arethusa

- Arielle Cottingham

- Atheism

- Byron

- Charles I

- Chartism

- Cian Duffy

- Claire Clairmont

- Coleridge

- Defense of Poetry

- Diderot

- Douglas Booth

- Earl Wasserman

- Edward Aveling

- Edward Silsbee

- Edward Trelawny

- Edward Williams

- England in 1819

- Engles

- Francis Thompson

- Frank Allaun

- Frankenstein

- Friedrich Engels

- George Bernard Shaw

- Gerald Hogle

- Harold Bloom

- Henry Salt

- Honora Becker

- Hotel de Villes de Londres

- Humanism

- James Bieri

- Jeremy Corbyn

- Karl Marx

- Kathleen Raine

- Keats-Shelley Association

- Kenneth Graham

- Kenneth Neill Cameron

- La Spezia

- Larry Henderson

- Leslie Preger

- Lucretius

- Lynn Shepherd

- Mark Summers

- Martin Priestman

- Marx

- Marxism

- Mary Shelley

- Mary Sherwood

- Mask of Anarchy

- Michael Demson

- Michael Gamer

- Michael O'Neill

- Michael Scrivener

- Milton Wilson

- Mont Blanc

- Neccessity of Atheism

- Nora Crook

- Ode to the West Wind

- Ozymandias

- Paul Foot

- Paul Stephens

- Pauline Newman

- Percy Shelley

- Peter Bell the Third

- Peterloo

- Philanthropist

- philanthropos tropos

- PMS Dawson

- Political Philosophy

- Prince Athanese

- Prometheus Unbound

- Queen Mab

- Richard Holmes

- romantic poetry

- Ross Wilson

- Sandy Grant

- Sara Coleridge

- Sarah Trimmer

- Scientific Socialism

- Shelleyana

- Skepticism

- Socialism

- Song to the Men of England

- Stopford Brooke

- Tess Martin

- The Cenci

- The Mask of Anarchy

- The Red Shelley

- Timothy Webb

- Tom Mole

- Triumph of Life

- Victorian Morality

- Villa Diodati

- William Godwin

- William Michael Rossetti

- Wordsworth

- Yvonne Kapp